Is there such a thing as being too successful, too influential, and too big?

We may find out in the months and years ahead as the world’s largest technology and consumer tech companies come under increasingly aggressive antitrust and regulatory scrutiny.

Government efforts to rein in Big Tech have been underway for years, but 2021 is likely to be a watershed moment. Political, societal, and market-based forces are converging to put these big companies under the microscope.

Furthermore, the Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated the growth of many tech companies during a severe global economic downturn. Of the largest US companies by market capitalisation, five are technology or digital businesses and their total market value exceeds $7trn — a figure that has grown by 54% over the past year alone.

Could big tech be subject to regulation and litigation?

That sort of size and growth often leads to antitrust and regulatory risk and recent evidence attests to this. The biggest US antitrust case since the government targeted Microsoft in 1998 was last October when the US Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit against Google, alleging the internet search giant stifles competition. In December, the Federal Trade Commission sued Facebook on similar claims that the social media network engaged in anticompetitive practices with its acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp.

There is no obvious way for these companies to make a few simple changes that will satisfy all critics. In the US, for example, Democrats and Republicans tend to have differing concerns about these companies, with the Democrats generally more worried about monopoly power, privacy, and the spread of misinformation, and with Republicans generally more concerned about the suppression of conservative viewpoints. Nonetheless, even when both parties seem to share the same objective – eg the suppression of speech that may illegally incite violence – a news article that strikes one side as provoking hatred might seem reasonable to the other.

US politicians and regulators seeking to limit the power of Big Tech are in some cases looking to Europe for inspiration. European authorities have been far more aggressive in their regulatory efforts. The European Union was the first to enact major online privacy laws in the form of the 2018 General Data Protection Regulation. EU officials have since followed that up with a series of proposed regulations designed to block certain acquisitions, curb hate speech, and provide more information to consumers about how their data may be used for targeted advertising.

Interestingly, many regulations developed by and for the European Union are becoming de facto global standards, as the US-based technology giants, after doing the work to conform to EU standards, simply apply those same standards to the rest of the geographies in which they operate.

How should investors evaluate the outlook for Big Tech?

Given the potential for government intervention in the years ahead, an important question to ask is the extent to which the risk of adverse regulatory outcomes is priced into each stock.

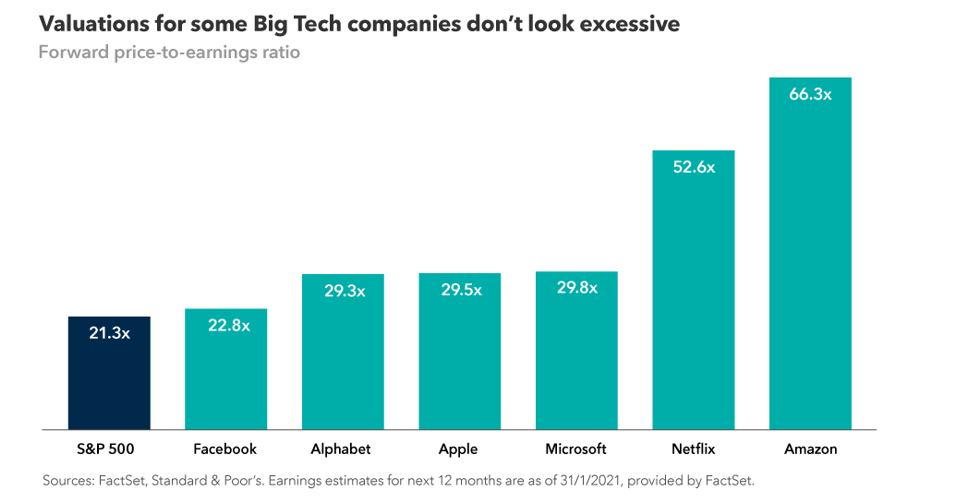

Among the Faangs, the two that are currently at the centre of high-profile lawsuits — Facebook and Alphabet — are trading at significantly lower price-to-earnings ratios than, for example, Amazon and Netflix. This suggests investors are discounting at least a certain level of risk.

Another question to consider is, what might happen to these companies if one or more of them is forced to break up? Counterintuitive though it might seem, a reasonable argument can be made that some of these companies could have a higher aggregate market valuation if broken up than if kept together.

Take Facebook, for example. Today investors tend to value it by applying a mid-20s multiple to the annual profits expected in the next year or two. This approach implicitly ascribes a negative valuation to the currently money-losing Oculus virtual reality business, and perhaps no value at all to WhatsApp, a hugely popular app that currently makes almost no money. As a standalone company WhatsApp could likely command an extremely high valuation due to its user base of more than 2 billion people in 180 countries. Instagram might also receive a much higher valuation than it does in Facebook’s current structure.

Similar arguments could be made for components of Alphabet and Amazon, and there are historical precedents – the forced breakups of Standard Oil and AT&T – in which investors eventually applied higher valuations to the parts when separated than they did when combined.

A third question that matters for these companies, and perhaps it’s the most important one in the long term, is not “what will governments and regulators do to these companies?” but rather “to what extent will these companies be willing and able to adapt successfully to the changing expectations of governments and regulators?” Companies that do not adapt successfully to the changing expectations of customers eventually fail. For Big Tech, how they adapt to the views of regulators and governments may be just as important.

Mark Casey is an equity portfolio manager at Capital Group