Demographics and debt creation are the twin engines that drive demand and, consequently, economic growth and, indeed, inflation. Historically, growing populations fuelled demand for goods and services, stimulating economies. However, a key demographic shift is taking place: declining fertility rates are falling well below replacement rates. It’s a long-cycle, global trend with potentially worrying consequences.

See also: Knacke’s money maps: Shine on?

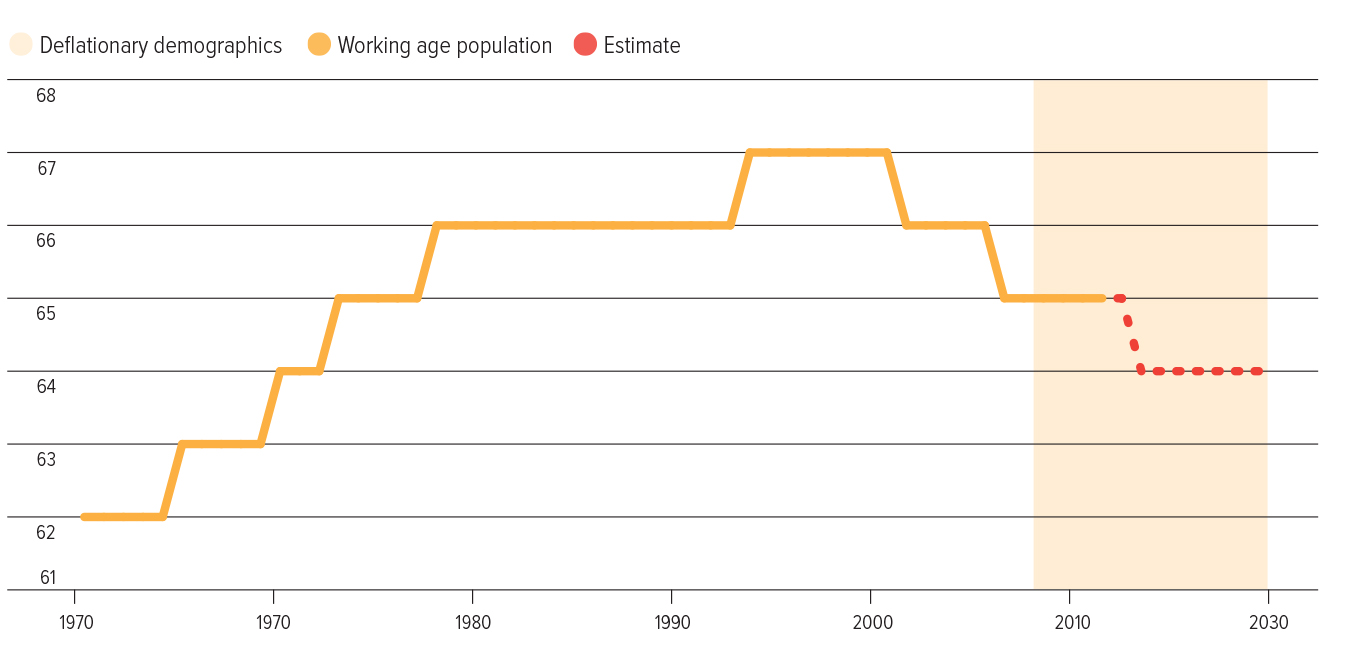

Japanese fertility rates first dropped below the 2.1% threshold – the level required to maintain a stable population (in the absence of immigration) – in the 1960s. In Europe, it fell below this level by the 1980s, and the US reached this point in 2008. Globally, with the exception of Africa, every major region now experiences fertility rates below this replacement level. The result is inevitable – a shrinking labour force, as more people retire or leave the workforce than enter it. This demographic imbalance threatens future demand and economic growth and increases the risk of deflation, as well as exacerbating cyclical dynamics.

Working age population, as % of total, OECD countries

To support demand, governments have been printing money and increasing spending to unsustainable levels. A recent UN report highlights that 3.3 billion people live in countries where interest payments on debt surpass what is spent on essential services such as healthcare and education. This situation is far from inflationary – instead, it reflects unsustainable government spending and the rise of the welfare state.

See also: Knacke’s money maps: Health is wealth

The reality is that the path forward for inflation appears volatile. We can expect secular deflation, as debt levels and economic strain begin to weigh heavily on demand, with temporary bursts of inflation triggered by excessive money printing and debt creation in what we call the ‘fiscal age’. We’ve seen this before in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This era was defined by extreme inflation volatility, underpinned by demographic shifts, supernormal debt creation, extreme wealth inequality and the rise of a new superpower.

I expect AI and new disruptive technologies that support productivity will continue to do well against this backdrop, as should real assets and stores of value that will withstand fiat devaluation.

But one thing is certain, without meaningful reform it is difficult to imagine reversing the current trends of rising inequality and declining living standards.

This article originally appeared in the October issue of Portfolio Adviser magazine