Coronavirus may have proved some competition this year but climate change remains public enemy number one in 2020.

We are nearing the limits of our ability to mitigate the impact of climate change and keep to global targets of a 1.5 degree increase in temperature. The International Energy Agency has predicted we need to invest $3.5tn (£2.66tn) in energy-sector investments each year until 2050, to be in with a chance of limiting global warming to two degrees.

More and more clients are now anxious to see how they can use their own investments to help close this funding gap and encourage the transition to a low-carbon economy. This objective is reasonable and understandable – but simply reinvesting into low-carbon portfolios may not be the most effective approach. Investors need to take a considered view on the best options to support the transition to a low-carbon economy.

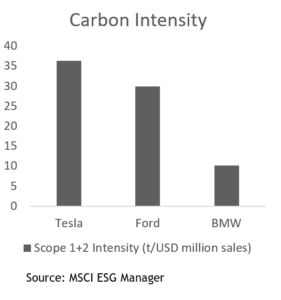

Tesla is well-known for its investment in sustainable solutions, including battery storage and, of course, electric vehicles. As the following chart illustrates, however, Tesla is also more carbon-intensive than, for example, Ford or BMW.

To be fair to Tesla, the figures used here are only Scope 1 and 2, or – in layman’s terms – the emissions generated by the company’s own operations and the energy used to power these operations. The data ignores Scope 3, where the emissions of the products once sold are also included.

Scope 3 is often excluded because the data is hard to calculate, and most companies cannot or will not disclose. Low-carbon indices and ETFs exclude companies on the basis of Scope 1 and 2. This means low-carbon tilts in portfolios can prove a crude measure.

Electric vehicles are currently more carbon-intensive to produce – particularly the battery. It is only through the life of the vehicle that it becomes more efficient (and only in countries that do not regularly use coal-powered energy generation).

This means low-carbon indices based on Scope 1 and 2 emissions or intensity do not necessarily exclude car manufacturers – even if they are doing nothing to facilitate the transition to a low-carbon economy. They do not rule out those companies where emissions are primarily generated by their products once sold rather than in the manufacturing process.

In contrast, a low-carbon approach would naturally exclude fossil fuel extractors, homebuilders and miners. Focusing on this last sector, mining is vitally important for many sustainable technologies. Cobalt, platinum, manganese, nickel, lithium – to name just a few – are vital for clean technology.

Miners may be dirty, but they are also essential. Some of these companies are mindful of their environmental and social impacts and as clean and careful as possible. As such, they are a valid and necessary part of the transition – is it right the sector should be excluded from a portfolio hoping to encourage a low-carbon economy?

Carbon footprints

While using carbon footprints can generate insights and flag areas of concern, it is a crude tool. It is possible to have a low carbon footprint while doing little to promote the transition to a lower-carbon economy or have a high carbon footprint while providing materials and tools for a low-carbon future.

Divestment from high carbon-intensive companies remains widely used. Global divestments from fossil fuel companies have reached $11trn, according to 350.org. The primary targets are largely thought to be the international public companies – yet oil remains a necessary component of our energy requirements and divestment can have some unintended consequences.

International public companies have high disclosure requirements and are subject to considerable scrutiny from the general public. The alternatives are state-owned companies – for example, Saudi Aramco, National Iranian Oil Company, Gazprom and so on – or private companies. The oversight of these businesses, especially from the public, can be non-existent.

There is a risk with mass-scale divestment that, in order to appear cleaner, or to maintain profit for remaining shareholders, big international companies will sell their more problematic assets to the smaller, state-owned or private companies.

This means that instead of well-governed companies, with strong environmental policies and shareholders and the public to answer to, these assets will be managed by those companies who do not face the same oversight and scrutiny.

Though a simplistic view, there is a chance that, by choosing divestment, the investor is not preventing assets being managed – just changing who is managing them. This could end up being more damaging for the environment.

Who can add most?

Looking at overall benefit, bypassing the energy giants in favour of smaller, low-carbon alternatives may seem sensible – however, many of these smaller companies also have the resources of smaller companies. Their capital for further green projects or research and development may be fairly limited.

If a titan such as Royal Dutch Shell chooses to commit its considerable resources, experience and connections to energy transition, green research and development, it could have a huge impact. In fact, Shell committed to spending up to $2bn a year on green energy from 2016, with plans to increase this level in 2020.

While Shell is currently struggling to hit those targets, the point still stands: if these international oil behemoths were to become greener overall, they have the power to make a far more profound and enduring difference.

Engagement is a key pillar of the UN supported Principles for Responsible Investment and the UK Stewardship Code. Engagement allows investors with a stake in a company to encourage real change and allows the active investor to generate an impact.

Most companies do not deny the reality of climate change or the risks it imposes on their businesses. Given the short-term nature of stockmarkets, however, putting in the time and money to transition and research can have an impact on the next set of quarterly results.

Positive action

Engagement can ensure management understands investors want positive action, plus their specific ESG expectations. It also allows investors to understand the challenges and opportunities a company faces and better shape their expectations.

Consistent data across companies and sectors remains a problem. Engagement can help give investors the information they need to analyse carbon-related risks and opportunities properly, as well as ensuring they start reporting along established guidelines – indeed, this is the main goal of the Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures.

Not all companies will be open to transparent communication or are ready to begin their transition to a low-carbon economy. This is where an investor must take this information and assess if they are comfortable to continue holding the company – both from an environmental and financial risk point of view. Divestment does have a place, but it should be reserved for businesses that cannot – or will not – change.

Sometimes, to make a real difference, pragmatism should triumph over idealism. Human beings naturally try to find the simplest solution. Removing an association with highly polluting companies is a superficially simple way to reduce the portfolio carbon footprint, but real change can only be created by more thoughtful investment and engagement.

Kate Capocci is an investment manager at Smith & Williamson Investment Management