They say all good things must come to an end and, if the rotation away from growth at the start of 2022 is anything to go by, we may be bidding farewell to the Faangs. The acronym, that is, not the individual companies.

Attributed to CNBC Mad Money host Jim Cramer, “Fang stock” was first uttered in 2013. Its earliest line up consisted of Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google, with Apple grafted on four years later to become Faang.

This clumsy acronym has been immune to the various changes some of the companies have undergone. Facebook is now Meta and Google is Alphabet – so, technically, it should be Amana or Maana or … you get the picture.

Unnatural bedfellows

They were grouped together by virtue of being hugely successful growth companies listed on the Nasdaq that were able to tap into a huge consumer base.

But let’s face it, there is little to genuinely tie these companies together.

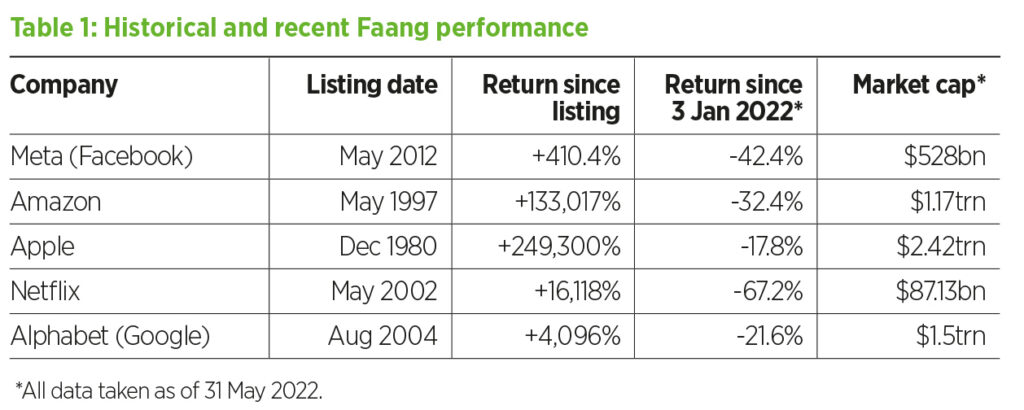

The oldest (Apple) is 42 and the youngest (Meta) is 10. Three have market caps in the trillions and two in the billions. Apple is worth nearly 28 times the value of Netflix. All are described as tech stocks, but that’s an incredibly broad church.

Amazon set out to disrupt the retail space and now derives a significant proportion of revenue from its web service. Netflix is an entertainment company. Facebook conquered the social media space, scooping up challengers and rivals along the way. Apple started in physical devices before expanding into software and online services, a mirror image of Google’s journey.

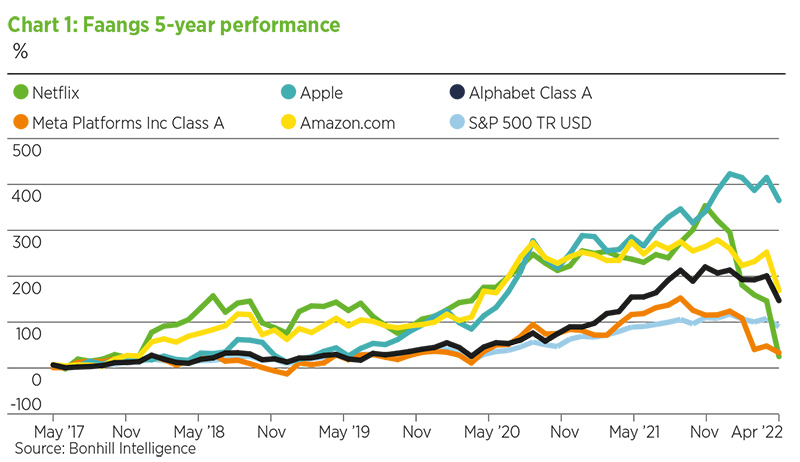

But for all their differences, their fortunes have very much moved in sync over the past five years as growth stocks performed well.

As the chart below shows, similar peaks and troughs can be seen over that timeframe.

For example, the Q3 2018 dip after Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell declared the US to be “a long way from neutral” only to later walk it back.

The onset of the pandemic triggered a wholesale panic, which can by seen in the drop in March 2020.

Only Netflix seemed immune. The online migration benefited these companies, with each holding considerable market share in their respective fields. So where did it all go wrong?

Less-than Nifty Fifty

For Ruffer investment director Alex Lennard it’s important to recognise that the individual Faang stocks “are no better or worse than they were six months ago when everyone loved them, and they were key assets in many portfolios”.

The valuation of these companies leading up to the start of 2022 “was entirely predicated on low rates and the certainty that growth would remain scarce”, he says.

“The rotation that we have seen has been driven by the fact growth has become less scarce, so investors have been less willing to pay a premium.”

With the exception of Netflix, Lennard says they have continued to perform “extraordinarily well”.

He flags US chocolate giant Hershey’s rough ride in the ’70s as an example of how a strong company can be hurt by a wholesale shift in sentiment.

Clumping companies together in a handy-dandy list is nothing new and back in the ’60s and ’70s it was called the Nifty Fifty.

In addition to Hershey, its constituents included McDonald’s, American Express, Coca-Cola and Pfizer – along with now less-famous names such as Xerox, Sears Roebuck and Polaroid.

Lennard’s fellow Ruffer investment director Duncan MacInnes wrote in October 2021: “As a quality business with growth and pricing power, Hershey was able to navigate the inflationary and economic volatility of the ’70s as well as anyone – successfully passing input cost rises onto consumers so revenue and operating profits grew handsomely over the four-year period.

“However, the equity market is not forgiving of economic uncertainty. Despite impressive earnings growth, the price of Hershey stock plummeted from $24 to as low as $8. The P/E multiple fell from 16x to 5x.”

MacInnes wrote: “In the ’70s, inflation didn’t just rot the odd apple – it brought blight to the entire orchard.”

‘Lost its magic dust’

Richard de Lisle, founder of De Lisle Partners, agrees that “nobody is criticising the Faangs, they are great companies, it’s just how they are valued”.

He, too, harkens back to the Nifty Fifty as being “analogous” to today’s predicament.

“As inflation built up back in the ’70s, these companies went more and more sideways into saucer shape formations. You can see the Faangs have come down one lip of the saucer.”

Given that “every single one is 25% below their high, some as recently as last November”, de Lisle can understand the growing urge to read the Faangs their last rites, but he says the industry “has gone through a whole period where everyone said it’s the death of the Faangs – and they were wrong”.

“It’s like the little boy who cried wolf,” he says. But that doesn’t mean they are without their considerable challenges.

With a 10-year bond at 3%, “money isn’t free anymore”, which is “badly wounding Netflix”.

De Lisle adds: “Amazon has also lost its magic dust. For 25 years it had a competitive advantage when it was tearing up retail. It had huge valuations but no earnings.”

But that won’t cut it anymore, he says. Amazon has delivered “another bad quarter [and] investor forgiveness for poor performance is a thing of the past”.

“The things that made these companies great are being taken away as their monopoly power is being slowly broken down. With various fines and regulation, all their amazing competitive advantages are slowing being eroded.”

Add to that the rise of Chinese rivals, which cannot be acquired, and the state of play has definitely shifted.

Right in front of its nose

The rotation away from growth has, as Ruffer’s MacInnes poetically stated, “brought blight to the entire orchard”.

And it has been acutely felt by the team at Baillie Gifford, says director of marketing and distribution James Budden.

“It’s a difficult marketplace for a business like us and we’ve seen considerable falls across our portfolios, trusts and funds. And that’s falls not just in absolute terms but also relative to other managers who are perhaps more value oriented, closer to the index.”

He says: “There are a lot of extraneous and geopolitical factors which have affected the ratings of growth companies and I think it’s fair to say quite a lot of growth was pulled forward because of the pandemic.”

What has surprised him, however, is how “febrile” sentiment has been.

“The market is really just looking right in front of its nose”, hence the reversion to energy, financials, commodities and property, Budden adds.

“The market is reacting incredibly quickly to the smallest negativity around tech stocks.”

He points to a recent statement by Snap announcing it would not hit target, which saw the whole market go down.

“We’re not even invested in Snap but Scottish Mortgage went down 7% in a day. The reactions and volatility have been extreme and that’s uncomfortable.”

All five Faangs have been held by Ballie Gifford’s various vehicles at one stage or another.

Netflix still features across a lot of portfolios, with Amazon also making a respectable appearance. Meta, Apple and Alphabet were previously big holdings, with the latter really the only one still of note.

“The reasons we sold or trimmed these particular stocks is based on their ability to double or more from here over a five-year period, which is quite difficult given how huge they have become. The money, we think, is better employed in areas where that is possible.”

When offering an analogy, Budden looks at the more recent past and the Brics. Created by Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill in 2001, it stands for Brazil, Russia, India and China. South Africa was grafted on in 2010.

“Those markets have gone in completely different directions.”

Such acronyms are “ridiculous” and “not helpful”. A better way would be to understand what consumers these companies are targeting and the problems they are trying to solve, Budden adds.

Beware siren voices

It’s fair to surmise that the Faang era is over. It was, ultimately, a term that conveniently grouped some of the most exciting and fast-growing companies in the world in a way that was easy to pitch to investors – not unlike the Nifty Fifty and Brics.

But how many Faangs could still be described as exciting and fast growing?

And for anyone looking to “pile in and buy the dip”, Ruffer’s Lennard has a word of caution: “It’s unlikely they will ever realise the same benefits” as those who enjoyed the ride up.

As outlined in a paper entitled The Nifty Fifty Re-Revisted: “The usual moral of the Nifty Fifty story is that investors became too enamoured with growth stocks in the early ’70s and pushed the prices of their favourites to unjustified heights.”

Adding: “There was a substantial and statistically persuasive negative correlation between a stock’s December 1972 P/E ratio and its annual return over the next 29 years.”

Here, de Lisle offers up Amazon as a prime example. “In 2000, it went from just about nothing and got as high as $120. It was one stock at the top of the tech bubble that survived. But what people forget is if you bought at $120, it wasn’t until 2010 that you got your money back. It was a 10-year valuation reset.”

He expects the story will be very similar this time around, and it will take a decade, if not more, for a company like Apple to be worth the price it was before the revaluation.

De Lisle says bond market rallies might see arguments for backing these companies but warns investors “not to be swayed by siren voices”.

This article first appeared in the June edition of Portfolio Adviser Magazine