A decade of stagnation and setbacks has left many emerging investors disappointed in the asset class, with some claiming the investment opportunity there is over. These volatile, shallow and inconsistent markets – they argue – lack the robustness of performance of other international opportunities.

Such an argument is flawed. Over the last 30 years or so, the emerging markets have evolved – and indeed continue to evolve – and, as they mature, the asset class offers the prospect of several exciting opportunities for investors with insight and expertise.

Through the decades

International investment in emerging markets began with the opening-up of the first Asian economies during the 1980s. Investment flows picked up in the following decade – particularly in Latin America after Brady Bonds helped address excess leverage and create a more formal emerging market debt market.

With the privatisation of national companies and rapid growth rates among the limited choice of stocks available, thin markets generated fantastic returns. Crises in Asia and Russia in the late 1990s, however, brought that powerful upward trajectory to a juddering halt. International capital flows were swiftly repatriated to the US, where they found a home in the number of high-growth technology businesses listing as the dotcom bubble inflated.

Emerging markets really came into their own in the 2000s after the dot com bubble burst. Currency flows reversed, following rapid commodity-fuelled growth in the so-called ‘BRIC’ nations of Brazil, Russia, India and China.

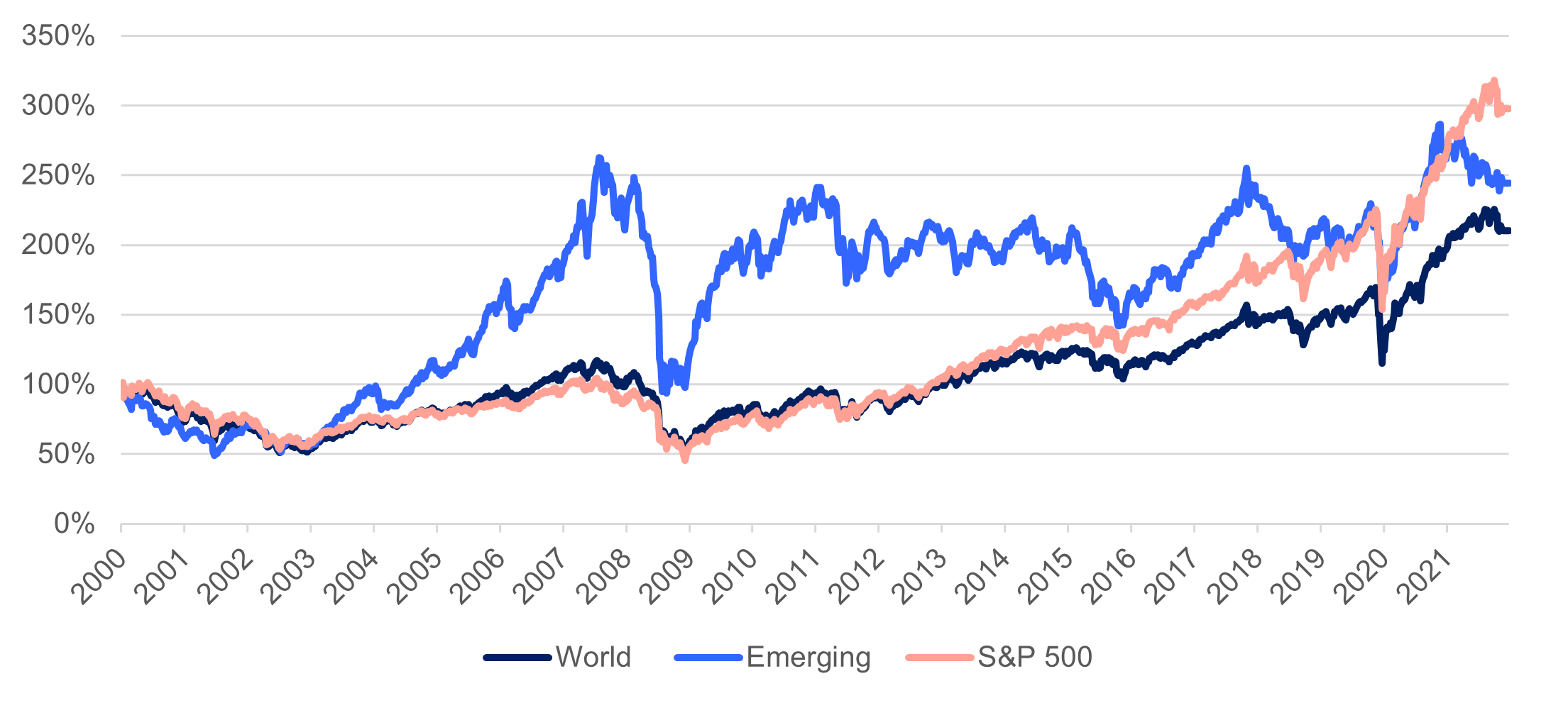

After the financial crisis of 2008, the Chinese government’s subsequent huge stimulus package only served to bolster this trend. Building cities and buying cars meant more demand for copper, iron ore and oil –with the other emerging markets best placed to deliver that. The asset class outperformed the US’s S&P500 index by almost 11% a year on average over the first decade of the 21st century.

By 2010, however, the shine was coming off emerging market economies. The gradual slowing of fixed capital investment and corresponding unwinding of commodity prices – after years of over-investment – resulted in slowing growth and de-rating stockmarkets.

Emerging markets began the decade not only relatively expensive – at one stage trading at a premium to their developed peers – but also dominated by cyclical industries including banks, materials and energy.

The US, in contrast, emerged from the global financial crisis with deeply discounted valuations and an index skewed to growth-focused sectors such as technology and consumer, which thrived in the new zero-interest-rate environment. As a result, the US delivered 15% compound annual growth rates versus 2% for emerging markets.

Emerging markets v World vs S&P500 stockmarket performance since 2000

Note: In US dollars, rebased to 2000. Source: Bloomberg

Towards the end of the last decade, the global economic recovery and the US Federal Reserve’s moves to tweak rates upwards coincided with a rally in emerging market growth. That trend was supported by the increasing presence of technology companies on emerging economy stockmarkets, helping to drive performance at an aggregate level.

The China conundrum

So much for the past – in the aftermath of a global pandemic that once again disrupted economic growth, where are we now? In addressing that question, it is useful, first, to recognise the importance of amenable, market-friendly political regimes. In this respect, emerging markets have broadly moved in the right direction but there have been some notable exceptions.

China and Brazil have both disappointed in recent years – with some market meddling in the former and a failure to deliver hoped-for reforms in the latter. Indeed, the most attractive and successful emerging markets are those where political volatility has been in the background – Poland, Korea and Taiwan being prime examples.

Direction of travel

The direction of travel for emerging markets economically has been positive, with central bankers handling difficult crises with increasing orthodoxy. Emerging market central banks are making generally prudent decisions – 2021’s rate hikes in the face of inflationary pressures in Latin America a notable example. Debt levels have risen in recent years but are generally far below their developed peers. Policymakers have learnt hard lessons over previous decades and are managing their currencies more prudently.

Another important point to make is it is no longer helpful to view the four BRIC constituents as anything like a coherent grouping – not least because Russia has achieved international pariah status as a result of its warmongering, something that may take years to shake off.

For its part, China’s stockmarket has more than doubled over the past five years to become the second largest globally, accounting for almost a third of the MSCI Emerging Markets index. Conversely, Brazil was a significant component of the index in the noughties but has shrunk to just 6% while India, despite strong economic growth, still feels underrepresented at around 13%.

Idiosyncratic cycles

Unlike many emerging market investors, we believe it is sensible to exclude China altogether from the investment universe. There are several reasons for sidestepping it in this way, quite apart from the regime’s recent interference in markets.

Importantly, such an approach facilitates diversification across a broader spectrum of smaller emerging markets at an earlier stage of their market development – especially those outside of north Asia, such as Brazil, Chile, Indonesia, Mexico, Peru, Saudi Arabia and South Africa.

So why now for these emerging markets? They are operating in more idiosyncratic cycles: they have less economic exposure to either the US or China and their stockmarkets have displayed far lower correlations with developed and Asian equity indices. Furthermore, their relatively low valuations reflect a lack of international ownership and present a contrarian opportunity.

At the same time, the attractive structural drivers are unchanged – in terms of GDP growth, demographic dividends and significant green field opportunities for growth in consumer, technology and financial sectors, especially for those digitally enabled companies, such as e-commerce and fintech. The scene is set to revisit this unique investment opportunity.

Fergus Argyle is co-portfolio manager at the New Capital Emerging Markets Future Leaders Fund