In his most famous speech, John F Kennedy committed the US to landing on the moon within the decade “not because it is easy, but because it is hard”. Had he been the chief investment officer of an asset management business, he might have instead opted for “positive returns in any market conditions”.

Turns out, getting to the moon and back in something with the computational capacity of a toaster is easier – and this has been the downfall of the Investment Association’s Targeted Absolute Return sector.

Promising the moon

The fund grouping’s commitment to “positive returns in any market conditions” is ambitious – so much so, in fact, that whoever drafted the sector definition actually added “returns are not guaranteed”, and that funds “may aim to achieve a return that is more demanding than a ‘greater than zero after fees objective’” in a period no longer than three years.

So, you may make more than nothing over the three-year period. But no guarantees.

Individual funds have beefed up the vaguer performance targets of the sector. One sector leviathan aimed to “exceed the return of six-month GBP LIBOR plus 5% per annum, evaluated over rolling three-year periods (before charges)”; another targeted “a gross return of 5% per annum above UK three-month LIBOR and aims to achieve this with less than half the volatility of global equities … over the same rolling three-year period”; while yet another aimed for “an average annual return of 5% above that of the Bank of England base rate, before the deduction of charges, over a rolling three-year period,” again, with less than half the volatility of global equities.

Five percent above six- or three-month LIBOR, less charges, is where the funds that have dominated the sector tend to be pitched. There are a variety of total expense ratios across the sector, ranging from more than 2% to a few basis points (bps), but the average is 1.3%. Three-month LIBOR is 13 bps at the moment; six-month is 16 bps. Let’s not quibble, and even things out to an annualised 4% to be hitting performance targets.

Turning tide

That promise initially held good, and assets flooded in. From 2013 to 2017, the sector beat all others in net flows. But then the tide turned: the sector has seen net redemptions every quarter but one (Q2 2018) since the third quarter of 2017. From then to the second quarter of this year, it shed £41.7bn. About £45bn remains.

One fund alone has suffered £24bn of net outflows over the period. Quarterly figures suggest much of this money circulated around the sector before heading out the door, but negative flows have been unremitting.

Such redemptions indicate the inability of the sector to live up to investors’ expectations. Which begs the question – were those targets viable?

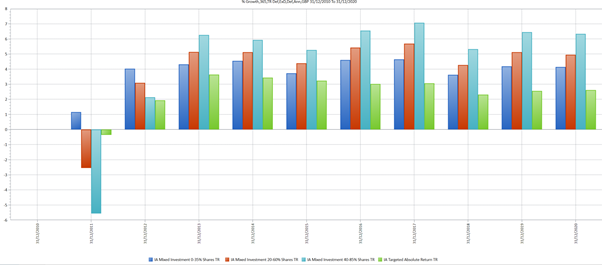

The three-, five- and 10-year annualised average returns for Target Return are 2.6%, 2.5%, and 3%, respectively – somewhat less than the headline figures that attracted investors. Also, as the following chart indicates, investors have generally done better from the Investment Association’s more “conventional” mixed investment sectors.

Targeted Absolute Return v Mixed Investment annualised returns over 10 years

Source: Refinitiv Lipper

Many paths, same moon

One of the characteristics of this sector is its complexity. At Lipper, we find we need 23 classifications to cover the 124 funds within the sector – from long-short equity over a variety of regions to global bonds, which themselves have diverse return characteristics.

Alternative Long/Short Equity Global funds within Target Absolute Return have averaged -9.9%, -6.6% and -1.5% over three, five, and 10 years, respectively. The funds grouped within Alternative Long/Short Equity Europe, however, have returned 5.74%, 4.5% and 5.2% for the same periods.

Diversity is not necessarily a bad thing here. It is fine to have outcome-oriented sectors, allowing fund managers to figure out how they get where they are going – as the Japanese Zen monk and poet Ikkyu wrote: “Many paths lead from the foot of the mountain, but at the peak we all gaze at the single bright moon”. Ultimately, however – to paraphrase a more recent ditty – while some investors did get a glimpse of the whole of the moon, others were left feeling they had just been shown a rain-dirty valley, took their cash and left.

Product complexity is sometimes used by pundits as a reason not to invest – generally when it is too late. That said, I may not understand the principle of the jet engine with any clarity, but I still get on the airplane. Or did, back when flying was a less hassle-laden process.

If a jet engine proves to be reliable technology, you are not going to want to grill the chief engineer at Rolls-Royce before trusting yourself to one of their creations. But if things continually go awry – even if it is just ending up in Kathmandu when you booked a flight to Copenhagen – you are going to think hard before going through the departure gate.

As the waiter famously asked George Best, where did it all go wrong? Perhaps, when all is said and done, the sector could never live up to its promises. I am always a little suspicious of financial engineering that promises that the – albeit moderately – good times will trundle on. And on. They seldom do.

Dewi John is head of research UK & Ireland at Refinitiv Lipper