War in Ukraine – in tandem with the energy insecurity that has created – has thrown the continuing upward trend of ESG investments into some doubt. Paradoxically, perhaps, it has also opened up what is, in fact, an ESG investment.

Take, for example, the fact the EU has moved to classify certain nuclear power sources as sustainable – and this at a time when some nuclear power stations have struggled with shrinking water supply as rivers sank because of this summer’s climate change-induced droughts. So, yes, you can call something “sustainable” – but the reality, should this continue, may be more problematic.

Broadening the boundaries of what could be considered a sustainable investment even further, arms manufacturers and dealers – those most feel-good of all professions – are now lobbying for their wares to be recategorised as sustainable.

The sustainable label is up for grabs by anyone and everyone, it seems – and German enlightenment philosopher GWF Hegel was no doubt thinking of just this when he wrote: “In the darkest of nights, all cows are black”.

As my Lipper Research colleagues Bob Jenkins and Detlef Glow have argued, the recent shake up in ESG is positive, leading to tighter standards and greater clarity. The environmental and social issues that engendered ESG have not gone away – indeed, quite the reverse.

Nevertheless, uncertain times for sustainable industries have come with negative flows for ESG funds –something almost unthinkable just a few months ago. In July, ESG equity fund sales in the UK went negative for the first time since the Covid-induced market meltdown, when even gold sold off.

Raising eyebrows

There is likely a value-versus-growth element to these performance swings – and I covered this broader phenomenon in PA back in May. Equity outperformers year-to-date have been from sectors such as oil and gas, miners and consumer staples, which have benefitted from supply-chain disruptions. These tend to be value stocks.

What is more, they also tend to be non-ESG stocks – but not always. There is no reason why consumer staple stocks cannot be sustainable – many score well, many do not. Miners can justify their place in an ESG portfolio through a focus on the metals and minerals necessary for renewable energy, whether aluminium for wind turbines or cobalt for batteries. Better still, if they can demonstrate responsible labour practices.

You might raise an eyebrow at the inclusion of oil and gas – and, personally, I am sceptical of the sustainability claims of this sector. But in the fund world, where managers frequently use ‘best-in-class’ screens, this too can be justified. Four Equity Global Income funds sold in the UK and classified as SFDR Article 8 (aka ‘light green) have more than 10% in oil and gas companies, for example – indeed, one has more than 16%. By way of comparison, the MSCI World index has slightly less than 5%.

You may view this as a way of encouraging best practice in a vital sector or you may believe it is as valid as picking a best-in-class drunk driver. That point is not made to pan ‘best-in-class’ – in principle, the idea is totally valid – but to illustrate that both perspectives exist within the market, which duly provides for the implementation of both through appropriate product.

Nevertheless, generally, sector tilts are discernible: ESG funds will tend to have lower oil and gas exposure than their conventional peers – if for no other reason than one of the main requirements of ESG investors, particularly institutional ones, is that they have a lower greenhouse gas footprint than the market average. That is hard to achieve if you are overweight oil companies.

One-trick pony?

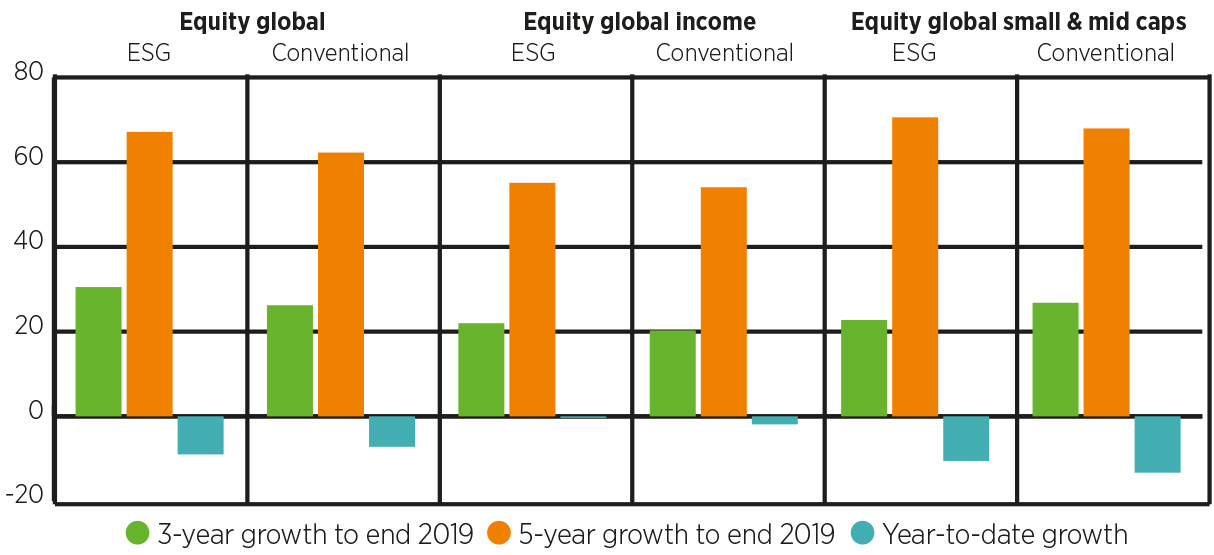

Does this explain the differing performance between ESG and conventional funds? Performance-wise, are they simply growth one-trick ponies? To answer this, we looked at three Equity Global classifications – standard, Income and Small & Mid Cap, as set out below – to see if any clear patterns were apparent, taking periods when growth or value clearly outperformed.

Equity global performance and sector exposures (%)

Source: Refinitiv Lipper

The graph above shows there is more going on than just a change in style leadership, as growthy-Global gets overtaken – year to date – by value-biased Income. That would be potentially sufficient to explain the outperformance of Equity Global Income over Equity Global over the period. It could also explain the outperformance of non-ESG over ESG within Equity Global over this period. What it does not help with, however, is the outperformance of ESG Equity Global Income over conventional Equity Global Income.

In small caps, as with the main global equity classification, oil and gas exposure is lower in ESG funds than in conventional. Nevertheless, ESG outperforms conventional year-to-date in this classification. The differences in oil and gas sector exposures between ESG conventional funds are not particularly large: in Equity Global the exposures are 3.8% for ESG and 5.4% for conventional. For Equity Global Income, the oil and gas exposures are 5.5% for both.

Looking at things from the other end of the telescope – growthy Technology – adds another dimension. Lipper Global Sector Energy, which comprises funds with a heavy weighting to oil and gas, rose 30.5% over the year to end-July, while Lipper Global Sector Information Technology funds fell by 21.2%. That indicates the impact of sector exposure on diversified funds will be considerable.

Interestingly, the largest gap between ESG and conventional funds with tech exposure is in Equity Global Income, with ESG funds surprisingly four percentage points behind their conventional peers. The same is true, to a lesser degree, with small caps, where the gap is two percentage points.

Mere phlogiston?

How does this help explain ESG performance? Certainly, there s more to ESG than a play on growth – something addressed in a paper from Robeco’s quants team and discussed in the ‘Klement on Investing’ blog here. Sector exposure effects have likely been significant and a combination of oil and gas and tech point in the direction performance has gone – at least in broad terms.

Is there a ‘residual’ ESG effect? Existing research is mixed and, unfortunately, this analysis does not resolve it. The argument that ESG provides an extra layer of due diligence makes intuitive sense – and one that will come to the fore if and when governments and regulators act against companies seen to pose particular environmental or social threats. That, after all, has long been the central plank of the unburnable carbon thesis.

The search for ESG alpha may turn out to be as fruitless as that of chemists of bygone ages for supposedly key elements such as phlogiston or aether. Does that matter? We all love a free lunch, but they are few and far between in investment markets. Instead, current performance should make us more aware of how to position in a world that is having to grapple with climate change and the consequently changing investment landscape.

As my colleague Bob Jenkins argues: “What we’re witnessing isn’t the beginning of the end but rather a calling out of ESG for very real shortcomings that will lead to a needed maturing and focusing on the material issues and underlying performance metrics.”

Maturing, rather than simply aging, requires the shedding of illusions. The world today is providing plenty of opportunities for ESG investors to do that.

Dewi John is head of research UK & Ireland at Refinitiv Lipper