When Dani Hristova stepped into the role of chief executive of the Independent Investment Management Initiative (IIMI) in May 2023, she inherited an organisation with deep roots in post-crisis reform – and a mandate that now stretches far beyond regulation alone.

Founded in 2010 in the aftermath of the global financial crisis (then known as the New City Initiative), IIMI was created by boutique asset managers struggling to operate in a regulatory regime designed largely for banks rather than investment firms. Some 15 years on, its mission has evolved to meet the demands of a client focused on value for money, but its core purpose remains intact.

“It was a relatively small group back then of boutique asset managers who were grappling with a behemoth of incoming regulation since the global financial crisis… regulation that was more suitable for banking rather than the asset management sector,” she tells Portfolio Adviser.

Today, IIMI represents 56 member firms, up from 38 when Hristova joined in 2023, and around £720bn in assets under management and advice. Its scope has also widened beyond the UK, reflecting a growing international membership base.

See also: Artemis and Brickwood join IIMI

What defines a boutique?

As the membership base has grown, the definition of a boutique has also evolved and IIMI now operates with a formal inclusion framework rather than a loose definition of “boutique”, Hristova comments.

“The unifying factor across all of our members is that they employ a degree of specialism.

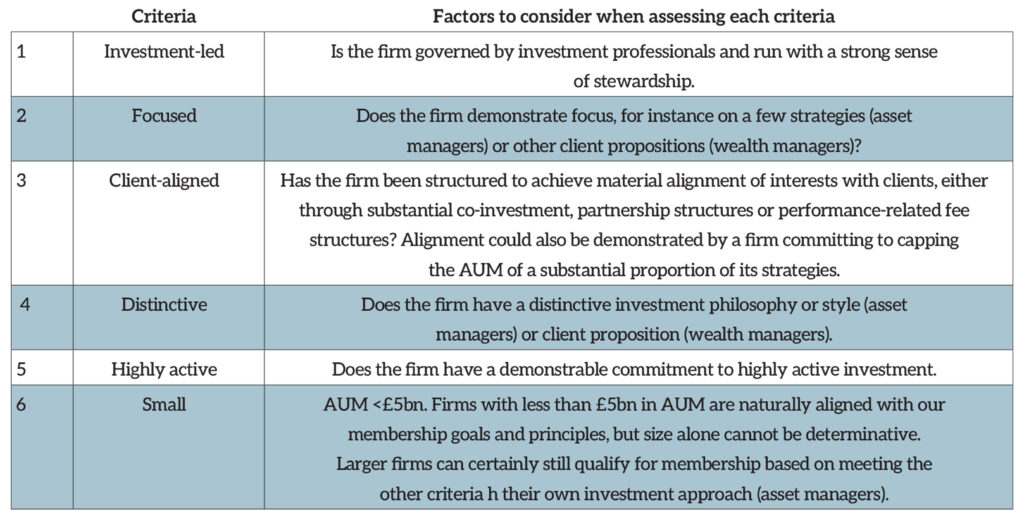

“We have also said only privately owned investment firms are eligible and then we have six criteria, of which groups must meet at least four of.”

These are:

IIMI’s published framework also defines “small” as AUM below £5bn, while “highly active” portfolios are typically those with an active share above 80%.

“We wanted to be very clear on who it is that we’re accepting as an independent investment management business… but also recognise that these businesses are evolving and not all boutiques look the same,” adds the CEO.

Regulation, promotion and best practice

Regulation is still very much a dominating consideration for boutiques and is one of three core interconnected pillars at IIMI: regulatory engagement, sector promotion and best practice.

Hristova also explains the third pillar – best practice – has evolved into cross-functional peer networks spanning compliance, operations, HR and governance.

“These businesses are very small and people wear multiple hats. If we can create peer groups or networks with like-sized, like-minded firms… then we can support these firms in all ways.”

The result, Hristova says, is IIMI has a more practical and holistic understanding of what boutiques need to scale sustainably.

See also: Baillie Gifford joins the Independent Investment Management Initiative

Start-up challenges

There are still a number of regulatory gripes for boutiques the IIMI continues to call out.

“The barriers to entry for launching a fund management company in the UK are quite significant relative to other jurisdictions,” Hristova says.

For example, IIMI’s research highlights that launching a new fund management company in the UK can take nine to 18 months, with direct regulatory and professional costs often exceeding £100,000, and total set-up costs in some cases approaching £1m.

Hristova says this contrasts with jurisdictions that operate simplified professional-investor regimes, such as the US, UAE, Luxembourg and Ireland.

“We needed a mechanism to be able to get entrepreneurialism back into the UK, [there are] fewer investment choices, fewer new businesses starting, less innovation, and a loss of talent.”

As a result, the IIMI, alongside Peel Hunt and Hill Dickinson, last year put together the UK Fund Management Start-Ups proposal, creating a template for globally competitive centre for new UK fund management companies.

It argued the current environment deters new fund management companies, highlighting the costs, bureaucracy, time and uncertainty as key challenges, while also holding back diversity – those looking to start a fund management company must have deep pockets.

It also added actively facilitating the launch of new investment companies would increase economic growth and support UK capital markets.

Encouragingly, Hristova said momentum is building in the UK.

“For the first time since the global financial crisis, the FCA, under the guidance of the Treasury, have been remitted to rationalise and streamline rules and regulations. They are looking at how they can remove unnecessary rules and regulations that are not helping businesses and financial stability, and create rational, proportionate rules that are not stifling growth.”

She points to HM Treasury’s 2025 policy update on creating a provisional licences authorisation regime, which would allow early-stage firms to receive time-limited permissions while working towards full authorisation, reducing upfront friction, and also the Treasury’s new concierge service – delivered in partnership with the FCA, PRA and the City of London Corporation – to help firms navigate regulatory and practical hurdles when establishing in the UK.

“What we’re asking for is a regime for fund managers who are targeting professional investors only… then once they reach a threshold, they graduate to being fully authorised,” Hristova reiterates.

See also: Industry group calls on FCA to cut barriers to entry for fund managers

Repositioning of active management

Another key issue for boutique firms is the ability to compete with low-cost, passive giants. But Hristova said rather than framing active management as cyclical, it needs to be repositioned as structurally essential to market health.

“There’s always a role for differentiated strategies irrespective of what’s happening in markets.”

She also links rising index concentration and correlation to hidden risk.

“Markets have performed so well for so long, and everybody is talking about the amount of concentration there is in indices, and the amount of correlation there is between indices. People have been buying indices like the S&P 500 and think they’re getting a diversified group of investments, but it can actually be quite concentrated, of course dominated by the magnificent seven.

“With the amount of concentration risk now, it is a good time to be thinking about differentiated strategies.”

However, Hristova also argues the case for active management goes beyond concentration risk. She quoted research from Sanford Bernstein in a recent piece for Portfolio Adviser: “The social function of active management is that it aims to direct capital to its most productive end, facilitating sustainable job creation and a rise in the aggregate standard of living”.

Conversely, she said, passive investing makes no such judgement and index strategies are inherently return agonistic.

“Their value proposition is to provide market rate of returns at the lowest possible fees.

“By contrast, active strategies seek to exploit and correct market inefficiencies – the mispricing of financial and economic value and ultimately to see their correction. Many also seek to influence management over a longer investment horizon to address these inefficiencies.

“Active managers have a particularly important role to play in this economic function.”

She highlighted this point again in our interview:

“Active management is judging the quality of management teams… capital allocation decisions… that is why it has an economic purpose.

“There are potential implications for financial stability with the rise of passives, it could make markets more volatile.”

She adds that, of course, she believes “there is always a case for boutiques” but more so in the current environment.

“Today it’s even more true there is a case for boutiques. We should be considering other strategies [from passives], more differentiated strategies, the alpha generators that have high levels of client alignment.”

See also: Goals and fears of boutique asset managers revealed

Scale versus competition

Another challenge for boutiques is consolidation, Hristova says, which has reshaped capital flows – often to the detriment of capacity-constrained, specialist firms.

“We’ve seen consolidation everywhere.”

This has most visibly been in wealth management and advisory firms, which have grown larger and investment decision making processes have changed.

“There are fewer, larger wealth managers and advisor groups.

“Investment decision making has moved to centralised investment committees and centralised buy lists.”

So, for boutiques, particularly those running single-strategy or capacity-constrained approaches, this creates structural barriers. Fee compression and platform concentration have also narrowed access routes for boutiques.

“They’re not gone, but the opportunities are fewer.”

Her concern again comes back to market structure.

“Smaller players compete with larger players on product, on specialism, on talent… when you remove those, you remove competition.

“What we really need is much more dynamism, entrepreneurialism, differentiation and innovation.”

Outlook

Hristova’s vision for the future of boutiques is, however, optimistic as conditions in the industry and market appear to be more favourable for specialist, client-aligned firms to grow.

“If we combine more searches for active, a recognition of concentration risk, and regulatory reform… we should see a turning point,” she says.

Regulatory change is not enough, she adds, and the defining feature of boutiques – the reason they exist in the first place – is at their foundation.

“The cornerstone of a boutique is culture.

“They want to have full autonomy; they want to be able to create a business that is client focused and client aligned – something they are not able to do in a larger shop. The culture piece is usually the reason or motivation for a boutique starting.”

IIMI is part of the ACT Alliance, supporters of the ACT [Action, Challenge, Transparency] framework developed by City Hive to encourage firms to commit to transparency around their culture and values, while Hristova also sits on the ACT Global Leadership Council.

“We have been working with City Hive to get this right from a boutique perspective as questions around culture may differ from larger firms. You need to get under the skin of that person to find out what drove them to launch their own firm, what parameters have they put in place to make sure their culture puts clients first and they are going to have long term success?

“The ACT mission is around open discussion and transparency, and I support that all the way.”

A strong internal culture, specialist expertise and a more supportive regulatory regime all contribute to a more durable future for boutiques.

Hristova adds smaller firms also have an advantage in more dynamic and able to adapt quickly to change – such as AI, technology and new ways of working – and therefore will always be part of a healthy investment ecosystem.

“If we have a regime where costs and compliance are coming down, where boutiques are able to put capital towards other things, and thrive and adapt, that’s the best combination that we want for growth and competition.”