Asia is tipped to be one of the top-performing investment regions over the next decade, but despite its high predicted GDP growth and favourable demographics, investors are not expecting China to do all the heavy lifting when it comes to returns.

The region has been thrust into the spotlight due to its better handling of the coronavirus pandemic, higher GDP expansion rates and the continuing growth of its middle classes. Improving China/US relations under a Joe Biden US presidency and the adoption of a greener agenda are also piquing investors’ attention.

The International Monetary Fund expects GDP in emerging and developing Asia to grow by 8.3% this year, with India tipped for a lofty 11.5% and China 8.1%. Elsewhere, the Asean-5 group – Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand – is expected to achieve a more modest 5.2% growth, but this is still higher than the largest developed markets. Indeed, GDP in the UK, euro area and the US is predicted to grow by 4.5%, 4.2% and 5.1%, respectively.

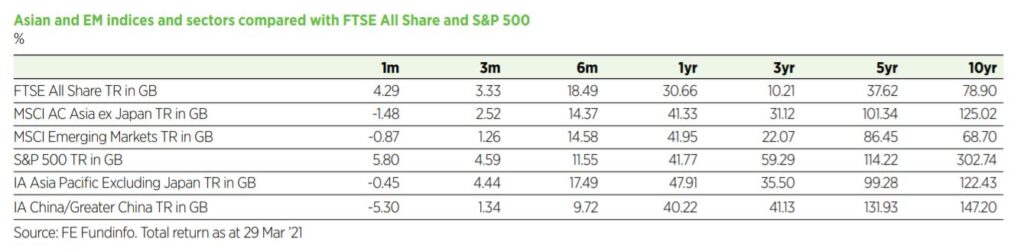

In the past year, the average fund in the Investment Association Asia ex Japan sector has produced a 44.5% return, while the MSCI Asia ex Japan index delivered 38%, pipping both the S&P 500’s 34.6% and the 30.7% of the FTSE All-Share.

There is also no doubt the demographic story within China is strong. Morgan Stanley analysts predict annual domestic consumer spending in the region will more than double over the next 10 years to $12.7trn (£9.24trn), with an emphasis on services rather than goods, putting it on a par with the US.

But beside these tailwinds, in China there is a perceived tightening of liquidity by the authorities because of the strength of the economy. At the end of last year, antitrust regulations were aimed at leading internet companies like Alibaba, whose planned IPO was eventually cancelled. On top of that, geopolitics with the US and the resulting sanctions on Chinese companies also weighed heavily

Look beyond GDP when looking at Asia

Man GLG head of Asia ex Japan equities Andrew Swan warns against assuming high levels of predicted economic growth means the underlying equity markets will perform strongly. Swan manages the Man GLG Asia ex Japan Equity and Asia Pacific (ex Japan) Equity Alternative funds. In the case of China, he says, the real driver of equity returns is corporate profitability and what drives alpha is relative earnings revisions.

“Identifying where that corporate profitability comes from and the surprise in particular to corporate profitability growth is how you should be thinking about returns in the region.”

Swan adds that China has been the primary driver of returns in Asia for some time, not due to its GDP growth but because of changes to its economy, evident in booming sectors such as technology and healthcare. “It has been a very narrow market within certain companies and sectors,” he says.

Candriam head of emerging market equity Jan Boudewijns also believes GDP is largely irrelevant. He says it pays to look at activity within the country, in particular how the Chinese authorities are planning to stimulate or slow down the economy.

He recalls China’s growth slowdown in 2017, which led investors to be cautious when, in fact, China was the best-performing market in Candriam’s strategies that year.

“We didn’t focus too much on the debt situation or the GDP numbers, but more on what was going on underneath the headlines – booming e-commerce and consumption.

“Infrastructure started to grow because the Chinese authorities were thinking if the economy was going to slow down, they had to invest more in that area.”

According to Boudewijns, the negative news surrounding China could tempt many investors to stay away, but stocks in cyclical areas like infrastructure, biologics, banking and tourism all continue to fare well as the nation shakes off its pandemic experience.

“You have to see what is going on in the market and then if you’re more cautious on the economy, you can still do a lot of interesting trades.”

He also thinks former US president Donald Trump’s hostile attitude towards China last year, particularly in the case of sanctions on technology companies, ultimately benefited the country as it forced policymakers to look inward at the economy and industry.

In fact, he says it was the worst thing the US could have done, because it led the authorities to issue enormous amounts of effort on technology, for example, digitalisation innovation and semiconductors. This was borne out in China’s latest five-year plan, which aims to increase research and development spending by at least 7% each year through to 2025, a move that should reduce the country’s reliance on US companies for semiconductors and other technologies.

It is not all about China

China is the largest constituent of the both the MSCI EM and MSCI Asia ex Japan indices, representing 41% and 43% in each, respectively, but there’s more to Asia than China.

India, which makes up just 10.2% of the MSCI Asia ex Japan index and 9.2% of the MSCI EM index, has higher predicted GDP growth for this year.

According to India Capital Growth Fund manager David Cornell, the fallout from the pandemic has highlighted the urgency for multinationals to diversify supply chain risk away from China, creating an opening for India to fill.

“India’s government has been preparing for this moment, formulating policies to attract new investment,” he says. “Corporate tax rates were lowered in 2019, land and labour laws have been consolidated to improve ease of doing business (see boxout below), while sector-specific production-linked incentive schemes have been introduced to reduce import dependency.

“The impact is positive as foreign direct investment flows reached all-time highs in 2020 as Apple, Samsung, Amazon and other global goliaths increased their production capacity in India.”

Swan believes Asia is at an inflection point because other areas, especially south-east Asia, are poised to usurp China as the region’s leader due to strong corporate profitability growth.

“The leadership of the region will start to change as we come out the pandemic and enter a world with twin stimulus, where you have both monetary and fiscal policy, which we have not seen for many years,” says Swan. “The policy environment we are moving into is supportive of a recovery in corporate profitability across many parts of Asia that have perhaps lagged behind for a long time.

“We believe it is time to look at the markets differently. We are in fact underweight China and overweight south-east Asia, particularly south Asia over north Asia, which is a change in direction.”

Greater China analyst Haiyan Li-Labbé says Carmignac also slightly decreased its China allocation in the Emergent Fund at the end of last year. This enabled the managers to gear the portfolio towards cyclical names and countries expected to benefit from the cyclical rebound and sector rotation, including South Korea, Brazil and Russia.

“This was a small adjustment, however, as we still have about 40% of the fund invested in our long-term convictions in China, mainly positions in the Chinese new economy sectors – internet, e-commerce, data centres, green technologies and clean energies,” she says.

Direct measures

Following its recent annual asset allocation review, AJ Bell decided to opt for direct China and India equity exposure rather than access them through an emerging markets or pan-Asia strategy. Head of active portfolios Ryan Hughes says, given the percentage of the world economy that China now is, lumping it in with Asia and emerging markets doesn’t make strategic sense.

Hughes believes the industry will reach a point over the next few years where there will be more products that are emerging markets ex China and Asia ex China because it is such a dominant part of the market.

“It almost doesn’t matter what your country allocation to emerging markets is, China has driven everything,” he adds. “We see value in having a dedicated allocation to both of those major superpowers.”

On the other hand, Andrew Hardy, investment director at Momentum Global Investment Management, allocates to broader Asia or emerging market strategies, preferring to leave the underlying asset allocation to the fund manager.

“We have been looking at China funds in more detail in recent years, but we’ve not made a decision to allocate to any specifically because we prefer the exposure we get from our existing Asia and emerging market managers,” he says.

Hardy favours active management because specialist stockpicking expertise is needed in such a large universe of stocks.

“We pocket Asia and emerging markets as one category, but it’s one of the most heterogeneous. China, Indonesia, Brazil and Mexico don’t move in lockstep with each other; and therein lies the opportunity for active management.”

Hardy notes solid performance from Asia exposure in portfolios has been heavily driven by China but expects that to broaden out as economic data improves as countries recover from the pandemic. A significant rebound in GDP, earnings and demand, as well as ongoing growth in trade and employment, should play into emerging markets’ hands, but particularly the cyclical parts of the sector that have underperformed in the past year, he says.

“It’s easy to miss perhaps that you’ve seen a very similar trend in emerging markets as we’ve seen in developed ones, whereby last year was very much driven by the ‘Faang’ equivalents in China: the virtual and stay-at-home trades. In fact, a large portion of the deep cyclical markets such as real estate have underperformed very significantly.”

This article first appeared in the April 2021 issue of Portfolio Adviser, out now