September marked an emphatic changing of the guard for the UK. The confirmation that Liz Truss would succeed Boris Johnson as prime minister and leader of the Conservative Party was quickly overshadowed by the death of Queen Elizabeth II. While the late monarch looked frail during her meetings with the incoming and outgoing PMs on 6 September, her death just two days later – after 70 years on the throne – still came as a shock.

It is only fitting, therefore, that the UK be the focal point of this edition of Portfolio Adviser magazine and, more specifically, that our cover story looks at seemingly perennially cheap UK equities.

There is no getting away from the fact that UK equities are ‘value for money’. They have been for several years and, taking into account recent events that saw sterling mimic the Titanic, that is unlikely to change any time soon.

Just 18 days after he was appointed, Kwarteng outlined a series of tax cuts and fiscal measures designed to stimulate the economy. Whatever his intentions and regardless of the long-term results, the aftermath saw the FTSE 100 and 250 stomach uncomfortable drops.

Even so, while skittish markets swooned in the wake of his ‘fiscal event’, UK equities have been heading south for a while. In the nine months to 30 September, the FTSE 100 is down 1.2% while the more domestically focused FTSE 250 has fallen by over 28%.

Leaving home

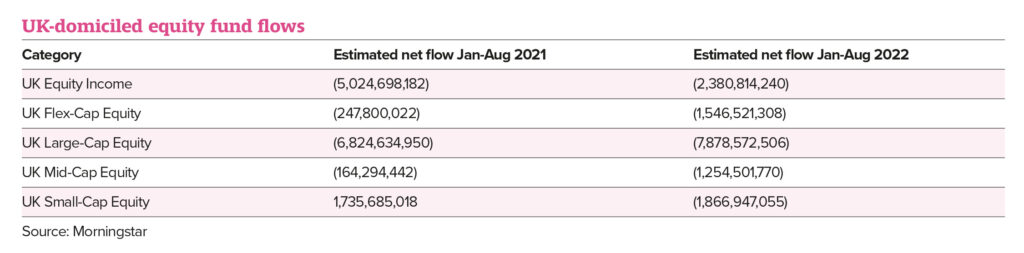

Data from Morningstar shows, over the first eight months of 2022, there were net outflows every month across all UK-domiciled UK equity sectors with just two exceptions. In March, there were net inflows of £53bn into flex-cap equities and £514bn into large-cap equities.

In total, £14.9bn was pulled from UK equities between January and August 2022, with the heaviest losses in the large-cap space. Compare this with the same period in 2021, when the only sector to record net inflows was small caps, although the £1.7bn it attracted was dwarfed by the £12.2bn in net outflows across the other UK equity sectors.

Despite this, Mark Preskett, senior portfolio manager at Morningstar Investment Management Europe, says the “performance in the UK equity market this year has been pretty good, relatively speaking, in local currency terms”.

He says: “We’ve quite liked UK equity markets, partly because of its valuation and partly because of its sector mix, which you have been rewarded for until recently where sterling really has come off.”

But a trend the Morningstar team has noted is a structural decline in the weight of UK equities within multi-asset portfolios and managed portfolios. “It has been steadily declining relative to the All-Country World Index, but managed portfolio and multi-asset managers have also been reducing their home bias quite materially,” Preskett says.

“You could go back 10 or 15 years and it wasn’t uncommon for clients to have 50% of their balanced portfolio in UK equities. Looking at the Morningstar MPS database, I would say the average now is down to roughly 25%. And there are some portfolios that have no home bias at all, in terms of UK equities.”

He says this is one of the reasons “the UK equity market, in terms of funds flows, looks so negative”.

As to whether home bias will ever go back to 30-40%, Preskett says it is “difficult to argue it will”. He says Vanguard has gone down to the low 20s in terms of its UK equity weighting and “I wouldn’t be surprised to see it stabilise from here”.

“There is definitely momentum against sterling at the moment and momentum is a powerful thing. Currency is a mean-reverting phenomenon, but it can often take seven to 10 years for a currency to mean revert, as it’s a slow-moving beast.”

Problems on steroids

With the prospects for UK equities back in spring “looking pretty strong, at least in relative terms”, Refinitiv Lipper’s head of research UK & Ireland, Dewi John, allowed himself “a little bullishness”.

“This was largely due to the UK’s advantage as a value-skewed market, in an environment where value was outperforming. That’s still the case, but US value stocks have caught up over the intervening period.”

Kwarteng’s funding of tax cuts through bond markets “has several implications”, John adds. “Bond yields have spiked, increasing borrowing costs. The Bank of England could increase rates to rein in inflation but, as we speak, the bank has decided to sit on its hands until November.”

As investors “took fright over the fate of the housing market”, real estate companies were hit the hardest in the wake of the mini-budget.

“The UK’s modestly sized tech sector also suffered, this being a worsening environment for growth stocks. Higher rates – now a more likely prospect than before, even if the can is kicked down the road to November – increases the cost of capital, so creating more problems for more indebted companies. Likewise, weaker sterling is good for exporters but bad for those reliant on imports. Those companies more reliant on foreign markets, both for exports and also where they operate, are likely a better bet than those that are domestically focused – hence why the FTSE 100 has outperformed the FTSE 250.”

John believes rather than creating new problems, it has “put the old ones on steroids”.

“‘Bird in the hand’ value companies are better placed than ‘two in the bush’ growth, while globally exposed large caps are less vulnerable than domestically focused companies, which tend to be lower down the cap range.

“Housebuilders are a case in point, set to be hit by higher import costs and crumbling house prices. However, the real question is how long this can go on. Will the government continue down this road, or yield to the pressures of the market and its own MPs? If the latter, then we’re in different conditions, and such beaten-up sectors could bounce,” John adds.

Little justification for low values

When Jo Rands joined the Martin Currie UK equity team in September 2021, talk very much still centred on inflation being ‘transitory’. “Wind forward a year and that is not the case at all,” the portfolio manager and research analyst on the large-cap team says.

“What we are seeing this year, in terms of sector movements, is two things. Large caps have performed way better than FTSE 250 mid-cap names. There has been a massive disparity in the performance of the indices. So, where you have been invested really has determined the level of performance you’ve had.”

She adds: “After the mini-budget we’re also seeing a continuation of the trend for at least the past nine months, in terms of the repricing of assets as we move to this higher interest rate environment.

“But it is a positive thing for UK equities. Especially in the large-cap space, valuations are low, so we don’t need bond yields to stay at a really low level for valuations to look attractive,” she adds.

When it comes to strong performers within the large-cap space, Rands points to defensive names like pharmaceuticals, value sectors such as tobacco, and oil and gas companies.

And there is “no real justification” for some of the low valuations, adds Preskett. “Look at Shell versus, say, Exxon Mobil. These are two very similar companies, slightly different earnings mixes, but Shell is trading on about half the multiple and there is no real justification for it. And that’s a discount that may, at some point, narrow.” He accepts, however, “it may take a few years”.

There is an argument that the companies which make up the FTSE 100 and 250 are too ‘old-world’, and the UK equity market is lacking innovation. It’s a criticism Preskett concedes is “justified”. But that doesn’t mean there is not still plenty of appeal for investors, in light of the “UK discount among even our larger, more successful companies”, he says, referring back to Shell versus Exxon.

“There are innovative firms within the FTSE but they are very small and it’s rare for one of these to grow with the index, as they are more and more regularly getting snapped up by US companies.”

Storms on the horizon

Kwarteng’s mini-budget proved to be anything but mini, and is but a stop-gap measure before an official budget is announced on 23 November, this time with scrutiny from the Office for Budget Responsibility.

What that will hold is really anyone’s guess at this stage.

Cracks seem already to be emerging in the relationship between Truss and Kwarteng, and some are [rightly] speculating the chancellor may not necessarily make it to the next budget.

But markets tend to frontload bad news, which explains the sharp movements in the days following the mini-budget. And while a healthy dose of criticism has been rightly launched at the government for its failure to ease the cost-of-living crisis facing the British public, measures to make the UK more business-friendly have generally been applauded.

Kwarteng’s extension of the Venture Capital Trust (VCT) and Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS) beyond April 2025 “shows strong support for the innovators and gamechangers who are the ones who will grow and scale the UK’s businesses of the future”, says John Glencross, co-founder of Calculus, the first approved EIS fund in the UK.

“The focus should enable more investors to continue to gain access to the diversified, strong-performing and tax-efficient natures of VCTs and EIS in the future.”

Wealth Club CEO Alex Davies says: “Removing this uncertainty should give investors the confidence to continue supporting this key engine of British innovation.”

He adds: “After many years it feels like we have got a government on the side of business and entrepreneurs that understands the value they bring to the economy and society. The [mini-budget] announcement will bring much-needed money into early-stage businesses at a time we really need it.”

This shot in the arm is no doubt long overdue and, in time, will reap benefits for the types of UK equities on offer to investors. The short-term outlook, however, is less rosy.

UK companies face considerable chills as the winter months close in. The year started with the hopes that Covid would abate, supply chain issues would be resolved, and economies would be merely inconvenienced by ‘transitory’ inflation.

What we got instead was China pursuing its policy of zero-Covid, Russia invading Ukraine, eye-watering increases in the cost of oil and gas, a painful pivot to much-higher-for-much-longer inflation, and central banks cracking open their 1970s playbooks and raising interest rates at levels not seen in a generation.

Outflows have been the name of the game for UK equities across the board in 2022. Against a backdrop of unabating uncertainty, that scenario looks set to continue. UK equities are cheap and have been for a long time – but they may have to get cheaper still before investors think it worth their while to venture back into the storm.

This article first appeared in the October edition of Portfolio Adviser Magazine