China’s economic data is normalising. Once again it is almost too good to be true. GDP in the three months from July to September grew 4.9% while most other large industrial nations are suffering recession.

Covid-19, of course, is centre stage. Investment optimism about Asia stems from its apparent success dealing with the pandemic. Doubts about responses elsewhere make for a more cautious outlook.

On China, let’s first think of the glass as half-empty. Close inspection of third-quarter figures should temper enthusiasm. It is lower than expectations – a Reuters poll of analysts last month had predicted 5.2%. Meanwhile, 4.9% is likely to look misleadingly high in the context of the year as a whole. October forecasts from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) suggest China’s economy will grow only 1.9% in 2020.

Sure – many will say that any growth in this year of plague is a substantial achievement. But 1.9% – and indeed 4.9% – is paltry compared with the supercharged rates of recent years. According to IMF figures, annual GDP growth averaged 9% between the turn of the century and 2019. Moreover, the IMF has pencilled in annual growth of between 5.5% and 5.8% between 2022 and 2025. It could be worse if China’s hard-line lockdown tactics fail to prevent the kind of second wave that has debilitated much of Europe.

Glass half-full

Now for the half-full glass. China has experienced no second wave as yet and there are few signs it will. Covid notwithstanding, growth rates are bound to slow as an economy gets larger and, sure enough, the average in China fell to 7.7% in the 10 years to 2019. Next year will see growth of 8.2%, says the IMF. Rising trans-Pacific cargo rates from international shipping non-governmental organisation BIMCO tell a similarly strong, corroborating, story.

OK, so the growth will slow to 5.5% annually in 2025, says the IMF. But lower rates of growth still equate to large year-on-year rises in the dollar value of the entire economy – and on individuals’ spending power. GDP per head in China, expressed in current prices, rose by $940 (£7320 in the high growth years of 2005/07 and by $1,700 in the slower growth 2017/19 period.

Another $5,400 of GDP per head will be added by 2025, according to IMF estimates, taking the total to around $16,300 per head. For comparison, UK GDP per head peaked at just over $50,000 in 2007 and was $39,000 at the last count.

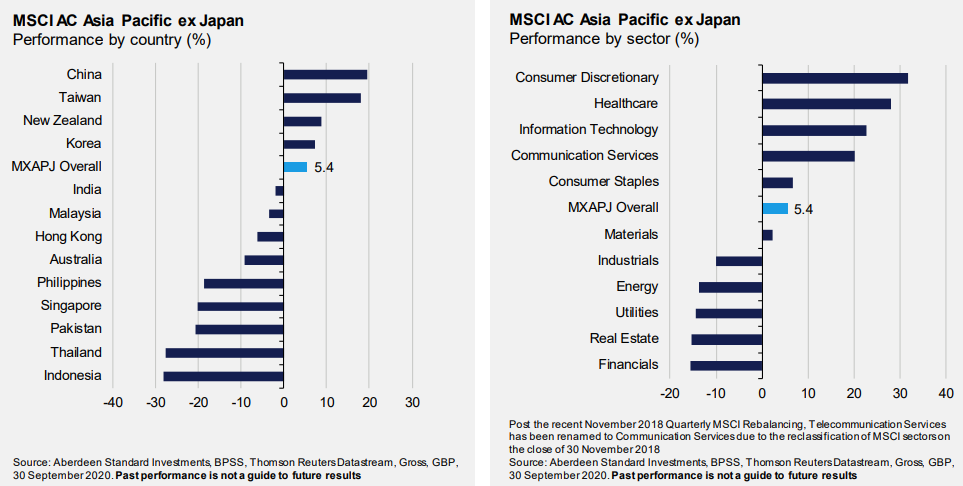

Asia ex Japan country and sector performance year to date

Source: Aberdeen Standard Investments – for year to 30/09/20

A similar picture can be observed with China’s neighbour Vietnam, where per capita GDP growth hopes are also attracting investors. “Per capita GDP in Vietnam recently passed $3,000,” says Craig Martin, chairman of Dynam Capital, which runs the Vietnam Holding investment trust.

“When Thailand got to this level, its per capita GDP doubled in less than seven years and, when China got to this level, its per capita GDP doubled in less than five years.” By 2025, he says, GDP per capita in Vietnam could be around $5,000. By 2035, it could be home to a further 35 million middle-class consumers. Its total current population is 97 million.

‘Second only to China’

“GDP growth is second only to China,” says Martin, “and it is set to end the year with a stable currency, low inflation and record foreign reserves. This marks a year in which Vietnam has chaired the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) through a pivotal year and received praise for its handling of Coronavirus. It was one of two countries to be visited by the UK’s foreign secretary Dominic Raab in an effort to win trade deals. Vietnam also hosted Japan’s prime minister Yoshihide Suga.”

Martin continues: “As China emerges strongly from the pandemic, the latest GDP growth numbers are encouraging. It will mean more demand for exports from Vietnam of agriculture – fruit and vegetables – and aqua-culture – shrimps and farmed fish – to China. Vietnam is a leading producer and exporter of both. It is also one of the largest pork producers in Asia.”

Enthusiasts such as Martin hope Vietnam will become a mini China, thriving on exports and developing consumer demand at home. It has shown China-like resilience to Covid as well.

True, it shares some of its neighbour’s problems. Like China there are questions over the reliability of corporate and national data and the power of its centralised government. Deteriorating US trade relations is another common theme. The Trump administration has, for example, indicated concern that Vietnam may be manipulating its currency – and has accused China of the same thing.

Trade tensions

The US-China trade tension has widened to industry, notably technology knowhow. As battle lines are drawn, there is little doubt where Vietnam secures its allegiances. Meanwhile, Vietnam has a particular issue – regulations make it hard, or at least expensive, for foreign investors to buy stocks.

Updating investors on a conference call on 21 October 2020, James Thom, manager of the Aberdeen New Dawn investment trust, described Covid as “the key variable”, adding: “There is a correlation between the countries that have handled the Covid-19 pandemic most effectively and market performance.”

“It’s been a rollercoaster year,” he said, adding that the north Asian markets of China, Taiwan and Korea were featuring strongly in terms of performance. Indonesia and Thailand are laggards in the context of the MSCI ex-Japan index. Covid responses make Thom cautious about India as well.

The questions raised by Covid mean that few things are as they seem – or may become in a matter of days or weeks. But is the China growth story too good to be true? Short answer? No.

Robert Cole is a writer for financial information website QuotedData