Retirement planning is not front of mind for the average Brit, even though automatic pension enrolment came into full effect in February 2018. Three in five British adults (59%) are now saving for the future, yet one-fifth, totalling almost eight million people, believe they will never be able to retire.

This comes despite a consistent upward trend of net assets moving into institutional funds which are largely made up of pension funds. The latest Morningstar data for a full year, shows these net assets to stand at over £187bn in 2018. Meanwhile, the share price growth of UK pension companies has been consistently positive since 2008.

For the past 15 years, Scottish Widows has monitored the annual pension saving behaviour of the British public using the Scottish Widows Pensions Index and Average Savings Ratio. Last Word Research has combined the insights of the three most recent reports to present a comprehensive outlook.

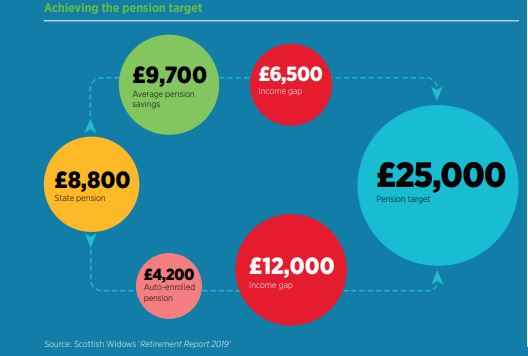

A comfortable retirement could be achieved for the average person at a cost of £25,000 per annum. However, this is harder to achieve than is commonly thought. The state pension is £8,800 per annum and the average Briton’s pension income is roughly £9,700, leaving an income shortfall of £6,500 before the £25,000 target.

These figures are based on the assumption that an individual is saving on top of the auto-enrolled pension. What is provided by the UK government alone would produce an annual income of £13,000, putting an individual at risk of poverty in retirement.

Scottish Widows’ latest ‘Retirement Report 2019: Adequate Savings Index’ reveals financial pressures are the key reason why many people find it difficult to save.

One of these pressures includes the housing market. Millions of young people are struggling to buy homes of their own, with 56% of 20 to 29-year-old renters unable to save for a house deposit.

In 1991, 67% of 25 to 34-year-olds owned a home, whereas in 2019 this number has dropped to 38%. Not owning a home will have a significant impact on an individual’s retirement income, affecting how much they can save for retirement as well as eating up a significant chunk of their pot later in life.

The report reveals that even those who are saving are disengaged from the process, with 38% of respondents unaware how much they are saving. This, combined with low saving rates, results in very few Brits who are planning or saving for the future.

Women and retirement

In some good news, there has been an improvement in the number of British women with a pension. In 2006, Scottish Widows reported just 41% of British women were saving enough. In 2019, this number rose to 57%.

This means a woman aged between 22 and 29 who starts saving now will benefit from an extra £5,900 in retirement income.

Despite this there is still a significant gender gap, and Scottish Widows predicts that, on average, a young woman today will have £78,000 less i

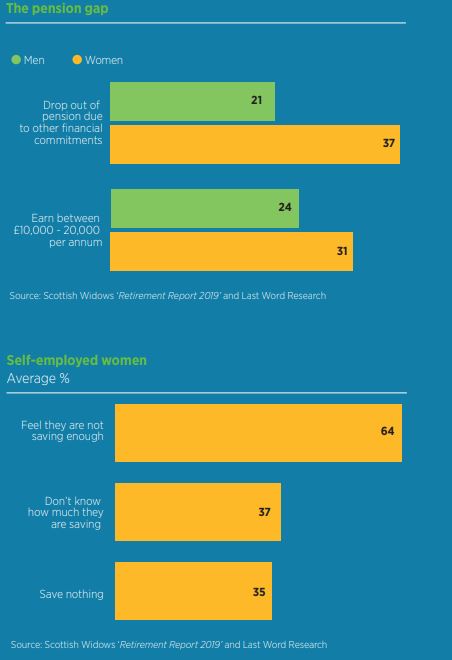

n her retirement pot than the average man. Women are much more likely to be in lower paid jobs, with 31% earning between £10,000 and £20,000 per annum. Similarly, women are more likely to drop out of their pension scheme due to other financial commitments.

More than six million women are part-time workers, making up 75% of the part-time workforce, meaning many are not eligible for automatic enrolment into the government’s pension scheme.

Similar issues are faced by those who are self-employed. Nearly 1.7 million women in the UK are self-employed. Of these, over a third have nothing saved for the future, 37% of these women do not know how much they have saved and more than two-thirds feel they are not saving enough.

In 2017, Scottish Widows’ ‘Women and Retirement’ report found women also lose out on £5bn each year as couples do not discuss pensions during divorce proceedings.

Similarly, as it is traditionally women who take maternity leave, the amount saved into a pension scheme or savings account is significantly reduced, especially as contributions to the fund cease after 39 weeks.

Next steps

The government’s auto-enrolment scheme was a good first step when it comes to planning for retirement but there is still lots of room for improvement.

First, the UK government needs to do more to help people save for the future. According to Scottish Widows, the British government must help self-employed individuals set up and collect savings, potentially through their tax. Similarly, it believes there should be greater flexibility to pension products and penalty free access to pension savings in times of financial hardship.

Scottish Widows also suggests getting rid of the minimum wage for auto-enrolment and lowering the age of enrolment would help those in lower-income jobs.

The British government and companies need to do more when it comes to inequality in the workplace. Enhancing maternity pensions, equalising paternal rights and shared paternal leave and statutory shared parental pay. There should be more consideration of pensions during divorce proceedings, too.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Equal Pay Act. As the UK works to diminish the gender pay gap, which is expected to close in the next 60 years, there must be more progress towards equality in all aspects of professional life, including pensions.

It is hoped that these changes will also bring significant improvements for female British retirees.

This article was written by Lottie McGurk, a quantitative researcher at Last Word Research