US lawmakers may have been locked in White House meeting rooms trying to thrash out a deal, but the consensus among investors has been that the debt ceiling problem will be resolved in the end.

That sunny optimism took a small hit on Friday as Republican negotiators walked out of the talks, accusing Democrats of being unwilling to have “reasonable conversations” on how to move forward.

Garret Graves, a Republican congressman from Louisiana and the key representative for Republican Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy said his side would “press pause” on the talks, bringing the prospect of the US government running out of money a step closer, though how close is hotly disputed. The Democrats say it could be as early as 1 June. The Republicans suggest July or August is more likely.

It is worth emphasising that there is a difference between a funding gap and a default, even though the markets might not see it that way. A funding gap means the government can’t pay bills in the short-term. There have been 22 funding gaps since 1976 in the US federal budget and 10 of those have led to some federal employees being furloughed without pay. Typically, they’ve been repaid in full at a later date and a debt-ceiling deal eventually completed.

A funding gap can last a matter of hours or even days. It does not equate to a debt default, where the government doesn’t pay the interest on its government bonds. This has never happened and would be catastrophic, affecting the US credit rating, its ability to borrow and proving significantly destabilising for equity markets.

Both scenarios remain unlikely. Beat Thoma, CIO at Fisch Asset Management, says: “Exceeding the X-date, in which the US Treasury prioritises interest and principal payments on government bonds but defers other payments – such as federal employees’ salaries – is seen as almost impossible. The even more unlikely scenario of an actual sovereign default would lead to violent market reactions and almost certainly trigger a deep recession.”

Libby Cantrill, head of public policy at PIMCO, agrees: “No one in Washington has any incentive to see the US default, but every incentive to try to extract as many concessions as possible in exchange for a debt ceiling increase. Of course, there will likely be more twists-and-turns until a resolution is struck, as no one is also really incentivized to compromise before the actual deadline, and even when a deal is reached, it will still need to be sold to rank-and-file members. Nevertheless, we remain confident that a deal will happen in time to avoid any sort of breech.”

Certainly, this is what has happened every time before. Since 1960, Congress has acted 78 separate times to permanently raise, temporarily extend, or revise the definition of the debt limit, under administrations of both kinds. The risk today is that politics are vastly more tribal.

Thoma says: “We expect the political debate on the debt ceiling to be even more contentious this time around due to the highly polarised political climate in the United States. It remains unclear whether any party will concede and how far politicians are willing to stretch it out, knowing that the X-date estimate is likely to be a conservative one, is a major issue.”

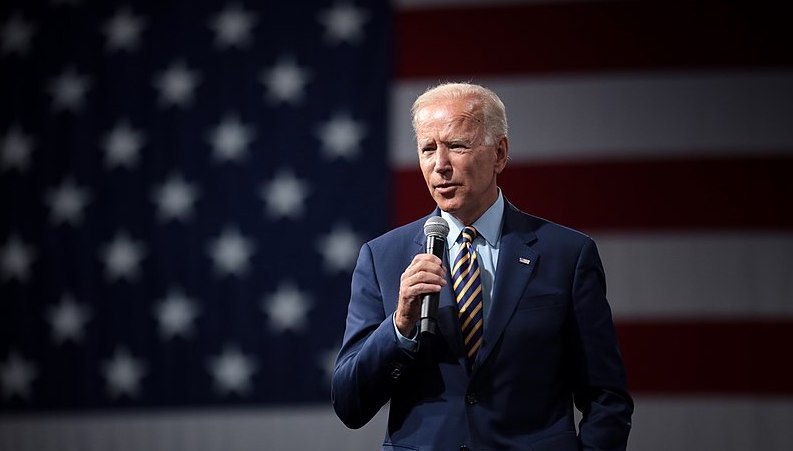

While some kind of deal will almost certainly be forged, but there may be second-order effects that are less widely discussed. For example, might Biden be forced to rein back the ambitious spending plans set out in the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS & Science Act? This could have real-world consequences for those companies that have invested in the assumption that government support will be forthcoming.

Craig Baker, global chief investment officer at Willis Towers Watson, managers on the Alliance Trust, says: “It’s so difficult to predict where the politics will go. We’re talking to our fund managers, asking about the companies they own and where they have exposure. There is a question over the second order effects and where Biden may have to row back. Some companies will be on the wrong end of this, but as long as investors have a diversified portfolio, they should avoid the worst effects.”

Another problem is that the current valuations of the US market leave little margin for error. Recent research by AJ Bell showed that, according to analysts’ consensus estimates, Standard & Poor’s and FactSet, America’s S&P 500 index trades on around 20x forward earnings for 2023 and 18x for 2024. By way of contrast, the FTSE 100 trades on 11.5x and 11x respectively. AJ Bell says that the US stock market has already started to ‘gently underperform’ other equity markets.

Thoma says the current brinkmanship will not be helpful and could exacerbate volatility. However, other areas might benefit from the weakness of the Dollar – he highlights safe havens, such as government bonds and currencies of the eurozone or Japan. He adds: “Paradoxically, however, a flight to safe US government bonds would also be on the cards, analogous to 2011, when the US faced a similar crisis. The gold price is also likely to rise further in the event of a severe debt or budget crisis.”

There is a final point about the debt ceiling that is worth mentioning. US debt is very, very high. While Republicans may make noise about curbing the debt in opposition, it has continued to go up under governments of every hue and there is no real political ambition to bring the debt lower.

Roberto Rossignoli, portfolio manager at Moneyfarm points out that the US government has significant depleted its reserves at the Federal Reserve over recent months, while debt servicing costs are likely to hit $900bn (£725bn) in 2023. Until there is a more permanent solution to the US debt crisis, the debt ceiling will continue to be a political football.