No company springs out of the ether fully formed and of sufficient scale to make waves from day one. All big companies start small and investors who get in on the ground floor can potentially ride winners up to dizzying heights.

But identifying those future behemoths just got a bit harder as the world adjusts to higher inflation and small firms bear the brunt of powerful headwinds that could see many go south for good.

US small caps, like their international peers, are already learning to cope with spiralling energy costs and persistent snaggles in the global supply chain. Add to that a strong dollar and the problems pile up pretty quickly. A recession is really the last thing they need, but one looks unavoidable.

Ahead of the US midterm elections, a Blackrock market update stated that equities tend to do better once the votes are all counted because “gridlock is common and prevents policy change that could spook stocks”. But it does not “see that past playbook working this time due to the recession we expect from the Fed ratcheting up rates”.

Recessions are not especially kind to businesses of any size but are most acutely felt by those on the smaller end of the scale, as they traditionally lack the pricing and purchasing power, access to reasonably priced capital and diversification of their much larger peers.

The basic rule of thumb for calling a recession is two quarters of negative GDP growth. But if that were the full story, the US would have been classed as being in one after delivering -1.6% in Q1 2022 and -0.9% in Q2.

The final decision, however, lies in the hands of the National Bureau of Economic Research’s (NBER’s) creatively named Business Cycle Dating Committee, which monitors peaks and troughs in markets and identifies if declines in economic activity are sector- or region-specific.

The committee may ultimately make the call, but the Federal Reserve will be the catalyst.

Markets got a reprieve with the release of the latest US real GDP figures at the end of October, which showed growth of 2.6% on a quarter-on-quarter annualised basis. Consensus had been for 2.4%.

“The four main indicators tracked by the NBER all remain in positive territory,” Evelyn Partners investment strategist Rob Clarry notes. “This should put an end to the debate that has raged over the summer as to whether the US economy is currently in a recession.”

That said, he expects “this rebound will be short-lived given the Fed’s aggressive stance towards elevated inflation”.

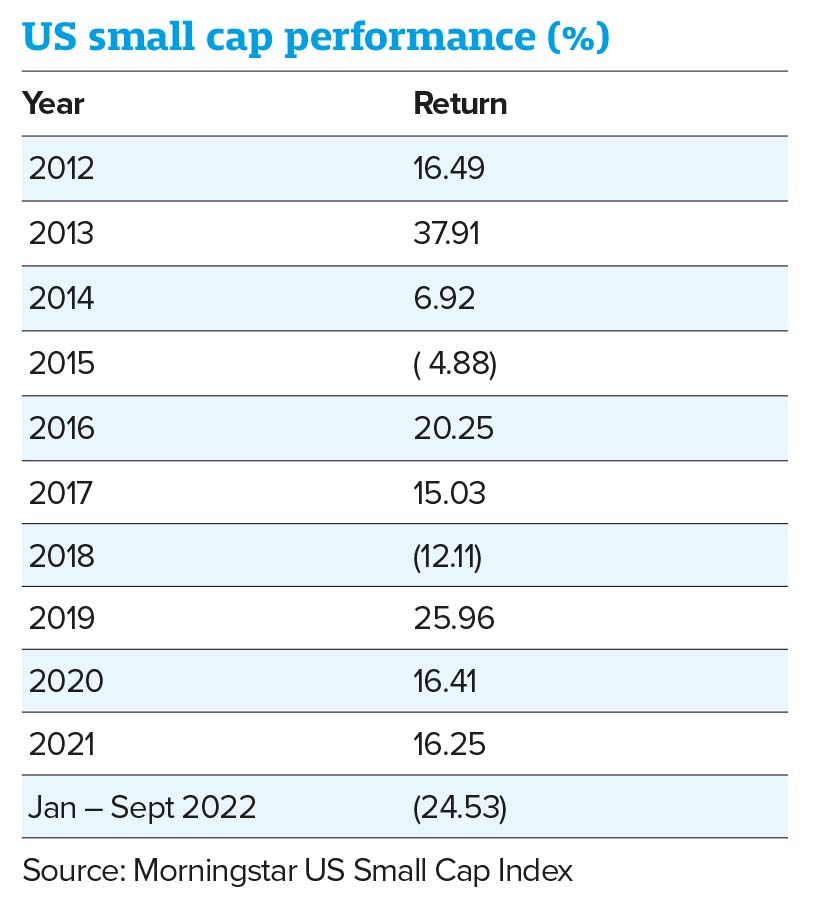

But it’s not just the prospect of a recession or results of the midterms that have turned things sour for US small caps, with 2022 set to be the worst year for smaller companies in the past decade in terms of performance.

Over the nine months to 30 September, the Morningstar US Small Cap index returned -24.5%. For the whole of 2021 it delivered 16.3%. If the situation does not vastly improve, 2022 will be only the third year in the past decade, after 2015 and 2018, in which US small caps have not generated a positive return.

Innovation hotspot

While the Morningstar index comprises 789 stocks that fall between the 90th and 97th percentile in terms of market cap, the Russell 2000 Index is home to more than double that number and is the most common benchmark for the performance of smaller and more domestically focused US firms.

Looking at the past three years, Felix Wintle, manager of the multi-cap VT Tyndall North American Fund, flags the 17.2% return of the Russell 2000 versus the 35.3% delivered by the tech-heavy Nasdaq. It also “lags the S&P 500”, he says.

“Over one year, it is -22.5%, which is worse than the S&P 500 but better than the Nasdaq. The Russell is higher-beta than the S&P 500 but has been lower-beta than the Nasdaq this cycle, as tech has been particularly weak and energy particularly strong, which has helped the small-cap index outperform.”

The Neptune Investment Management alum says the make-up of the Russell 2000 Index is “what makes it different to the other major indices”.

With healthcare its largest sector weighting at 18.1%, followed by financials at 16.1%, industrials at 15.2% and technology at 14.5%, he says “this means there is a strong focus on innovation in the index, as healthcare, industrials and tech are sectors that typically see new products and are growthy by nature”.

“The financials sector is predominantly made up of domestic banks and insurance companies where there tends to be less innovation, but it is an interesting window on the domestic economy,” he adds.

The VT Tyndall North American Fund’s current weighting to small caps is 6.1%. “Small caps are usually high-beta investments and so with our cautious and defensive outlook we don’t have a big weighting,” says Wintle. “As the economy starts to improve, we will increase our weighting to smaller companies.”

Artemis’ Cormac Weldon concedes, “if one were to generalise,” the concerns about US small caps raised at the start of this piece are “reasonable observations”. “In particular at the smaller end of small cap.”

He set up the Artemis US Smaller Companies Fund when he joined the firm in 2014. As it stands, the £1bn fund’s investment universe typically consists of companies with market caps that fall between $2bn and $10bn, meaning that Weldon swerves “the smaller end of small cap”.

“I am higher up the market-cap scale, even for a US small-cap manager.”

He adds: “Below the $2bn mark there are many companies that are loss-making and don’t have the scale to compete against large-cap companies, where borrowing costs are higher, etc. That being said, what I’m challenged to do is find 50 companies where that isn’t true.”

Like Wintle, Weldon points to the innovation on offer in the small-cap space.

“We’ve all heard of the ‘innovator’s dilemma’, where a successful large-cap company has a product that is producing nice cashflows, but they have to keep innovating and frequently that may involve simply making it cheaper.

“But if you’re the incumbent, with large market share, you’re not really incentivised to do that. But that’s where a small-cap company that doesn’t have significant market presence can gamble on innovating and perhaps gain market share.”

He points to the tech and healthcare sectors as examples of where such companies can be found.

Small companies can also “use a large company’s business model against itself”, Weldon adds.

Competing successfully with regional banking giants is no mean feat, but the rate at which M&A activity is ongoing has opened up an opportunity for one company in which Weldon’s fund invests. After Bank A acquires/merges with Bank B, there is often a group of “motivated entrepreneurs” who might not want to stay with the combined business, he explains.

“They wait for mergers to happen and then approach bankers in different cities and see if they want to set up a bank in, say, Atlanta or Nashville.”

But it’s not just about finding firms that are going to be future giants, Weldon says. Some companies, by virtue of their business operations, will always be small caps despite being the biggest players in their respective spaces.

“They can be slightly esoteric. One company we own controls 80% of the hazardous incineration capacity in the US. That’s not a big market, so there isn’t a JP Morgan or General Electric of hazardous incineration. But it’s an attractive market because, more and more things are being discovered to have been hazardous and, frequently, the most effective way of disposing of them in through incineration.”

Having the ability to invest up to, and even slightly beyond, $10bn “gives us plenty of freedom to not have to buy a competitively challenged, weak business,” adds Weldon.

Tailwind for industrials

One area in which he is seeing “quite big opportunities is industrials, including companies that are classified as being within the sector, driven by what we broadly call ‘infrastructure spending’”.

“The beauty is, at the moment, they tend to be largely domestic businesses, whereas international businesses have a strong dollar headwind. The energy transition is the most obvious, with the increased investment in renewable capacity. All of that has to be built.

“There are a number of aspects to the whole energy transition that require investment.”

He flags ‘grid hardening’ as one example, which involves fortifying the existing network to cope with increased demand. “You don’t want to be the third person in the street to get a Tesla, plug it in at night and all the lights dim.”

Solutions are also needed to protect the network from climate change, adds Weldon, which includes burying transmission wires in California so they are less vulnerable to forest fires and moving cables underground in Florida so they can survive hurricane-strength winds.

One area in which the fund is underweight is technology. It has held a number of software companies for several years but, about two years ago, he says the term ‘profitability’ starting overtaking ‘growth’ as the key metric. “We have reached a bubble in the valuation of unprofitable high-growth companies.”

Moving forward, Weldon sees the biggest tailwinds for small caps being president Joe Biden’s $1trn Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, as well as the “poorly named” Inflation Reduction Act. The latter “boosts quite a bit of the energy transition”.

Regardless of how the politics of November play out, Weldon doesn’t believe “there will be any appetite for reversing those acts”.

Echoing the comments from Blackrock earlier in the piece, he anticipates the next two years, as we count down to the next presidential election, will be “gridlocked”. “I don’t think Biden is going to get much done. But there is already quite a lot of fiscal stimulus in the pipeline, so I’m not convinced they need to do a lot more.”

The current economic environment is the biggest headwind for US small caps, adds Wintle. “[They] just don’t like risky markets as they themselves are riskier investments.”

That said, he believes the biggest tailwind is the “huge amounts of growth” some have ahead of them.

“The next multi-bagger, super-performance stocks will come out of the small-cap space, they always do. It’s easy to forget that all the big companies that we know so well today started out as small, unknown companies. For example, Wal-Mart started life as a listed company in 1970 when the stock traded over the counter and had a market cap of $5m (£4.33m).

“By 1990, a mere 20 years later, it was the biggest retailer in the US. Today, it is the biggest retailer in the world and has a market cap of $360bn. All great companies start small, and this is where the really great opportunities are for investors.”

This article first appeared in the November edition of Portfolio Adviser Magazine