By Dewi John, head of research UK and Ireland at LSEG Lipper

In September, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee paused rates at 5.25% for the second month running. Consensus (and I) got it wrong. Softer inflation figures for the month meant a majority of the committee took a wait-and-see approach. With higher energy prices still feeding through, there may well be more to come. Inflation generally, and in the UK in particular, has proven stickier than many predicted.

One of former US Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke’s best-known quotes is that the job of central banks is to take the punchbowl away before the party gets into full swing. But is anyone feeling “irrationally exuberant”, to use another of his phrases?

While there has been an uplift of demand—not least as economies opened up post-Covid—much inflation is down to supply constraints. Rate rises will have little effect on this aspect.

See also: What do ‘higher for longer’ interest rates mean for UK smaller companies?

Hammers and nails

What else can central banks do? Very little, in truth—but when your only tool is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Addressing constricted supply is a wider problem, not something on which central banks can have much impact.

One role for higher rates is the strengthening effect it has on sterling. There is a case for further tightening on this basis, and a danger of imported inflation if other central banks get ahead of the Lady of Threadneedle Street, especially given the UK’s dependency on goods/energy imports.

So, in the words of school-age backseat drivers everywhere, are we there yet? Have rates peaked? And if we are at or—surely likely—close to those terminal rates, how have fund investors been digesting this?

As we slide into autumn, investors grapple with the linked uncertainties of the threat of recession, implied by strongly inverted yield curves, and that persistent inflation.

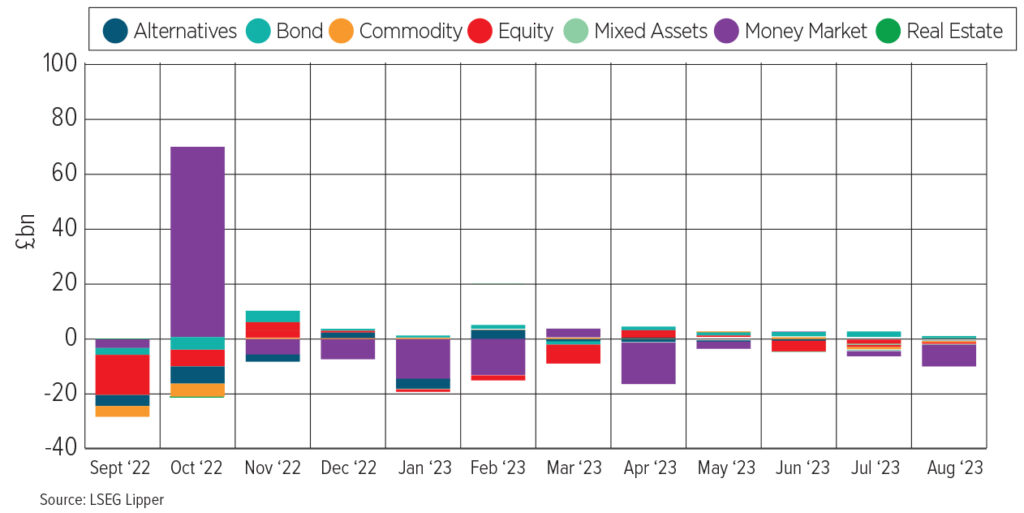

Year to the end of August, there have been outflows of £52.13bn from UK mutual funds and ETFs. However, £53.37bn has left money market funds alone—a hangover to no small degree from last September’s mini-budget—meaning long-term assets have attracted £1.25bn over the year to that point (see chart 1). Most of this has been to bond funds, which have taken £11.2bn over eight months, and £8.52bn into mixed-assets funds, counterbalanced by the £13.68bn of redemptions from equity funds despite their outperformance of bonds.

Have investors bought into the story that with growth faltering recession looks more likely and bonds should therefore outperform equities? US yield curve has been stubbornly inverted since Q4 last year. Yield curve inversion is a fairly (though not infallible) reliable predictor of recession within 18 months from first occurrence. And recession would very likely bring rates down, but that’s at considerable cost. That equity and bond correlations have trended up this century will take the shine off some of this, but the correlation isn’t total, so the idea still holds water.

Or is it that with yields having blown out, they are placing their faith in central banks reining in inflation and so are locking in a decent rate of return before everyone piles in?

See also: ‘Narrative-ruining’ inflation print stays at 6.7% in September

Higher for longer?

Can the bank continue to keep rates this high, or even tighten further?

Despite fears of a meltdown in corporate credit, there is unlikely to be a single moment when this hits. Corporate refinancing is spread over a number of years. This is likely to be more of a problem in high yield, with shorter-dated credit (and greater default risk). Nevertheless, that’s not something that investors seem to have reacted to yet. Looking at flows to the major high-yield bond classifications over the past quarter and year, there’s no clear signal that investors are fleeing the asset class.

This makes sense, as it’s a shorter duration area of the fixed income market, less pounded by rising rates over the recent period, and returns have consequently held up better than, for example, investment grade corporates or government debt.

Conversely, default is less of an issue in the investment grade space, with refinancing more stretched out.

However, there is a market disconnect: market-implied forward overnight rates show a much more gradual return to “normality” than market-implied inflation rates. If the former is correct—inflation is stickier and more structural—then this means more pain and higher defaults.

In the global financial crisis, cheap money got many companies through: “creative destruction” was deferred. This time round, things look less certain.

So, if inflation does persist, central banks seem likely to carry on with their existing playbook: raising more now, hoping that this will choke off inflation earlier, allowing them to drop sooner, avoiding this pain. But given this isn’t a solely (or even primarily) demand-side issue, it’s not clear how effective that logic will be.