Leo Tolstoy was onto to something when he wrote ‘happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way’. The quote from Anna Karenina is an apt metaphor for financial markets, where recoveries tread familiar ground, but every recession has its own unique set of circumstances.

As the chat around the financial services watercooler switched late last year from inflation to recession, the Portfolio Adviser team was inundated with forecasts. The recession will be ‘short and sharp’; ‘no, it will be short and shallow’; ‘wait, it will be long and deep’; ‘wrong, it is going to be long and mild’ etc.

Multiply those predictions by the number of major geographies and you get a sense of how disparate views on the topic have been and how much confusion abounds.

Complicated outlook

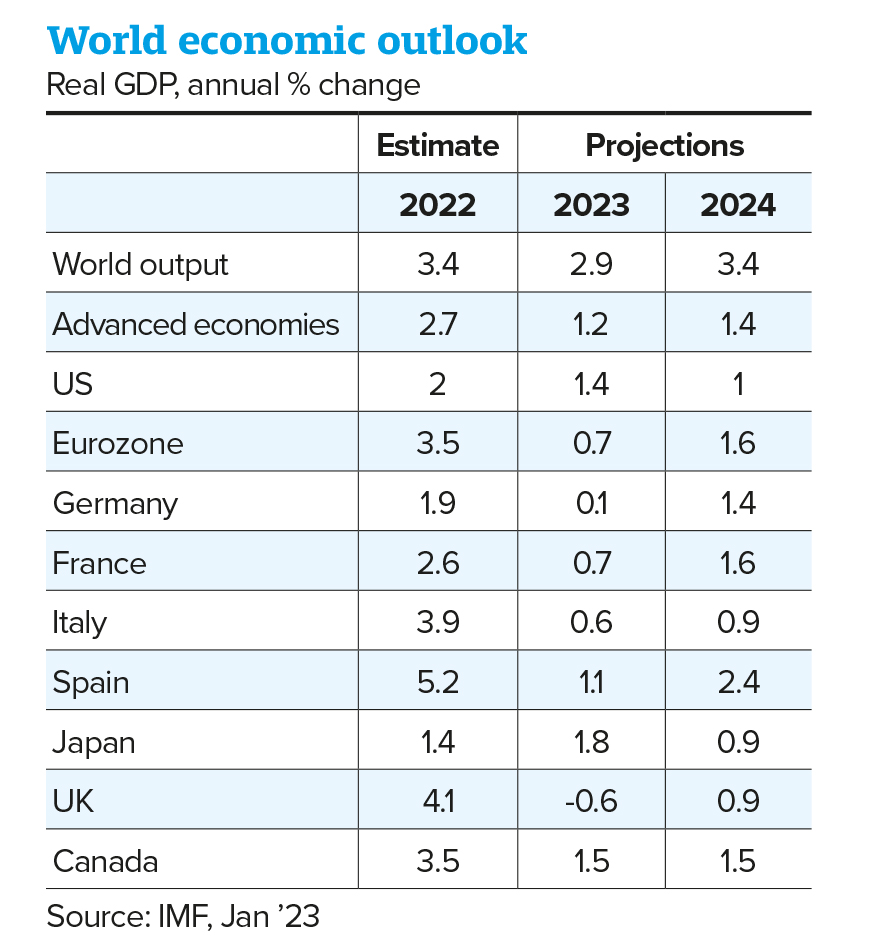

Concerns were turbo-charged in early January when the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) managing director Kristalina Georgieva said: “We expect one-third of the world economy to be in recession [this year].” She told CBS news programme Face the Nation: “Even countries that are not in recession, it will feel like [one] for hundreds of millions of people.”

Fast forward to the end of the month and the IMF upped the ante, at least for the UK, tipping it to be the only advanced economy headed for a GDP contraction in 2023.

But, taken at face value, the figures don’t look terrible and are not what would usually be expected in the run-up to a recession.

The latest UK monthly GDP figures show the economy grew by 0.1% in November, following a 0.5% uplift in October, according to the Office for National Statistics. The December figures were not released at the time of writing, but indicators suggest that a modicum of growth will be delivered during the quarter.

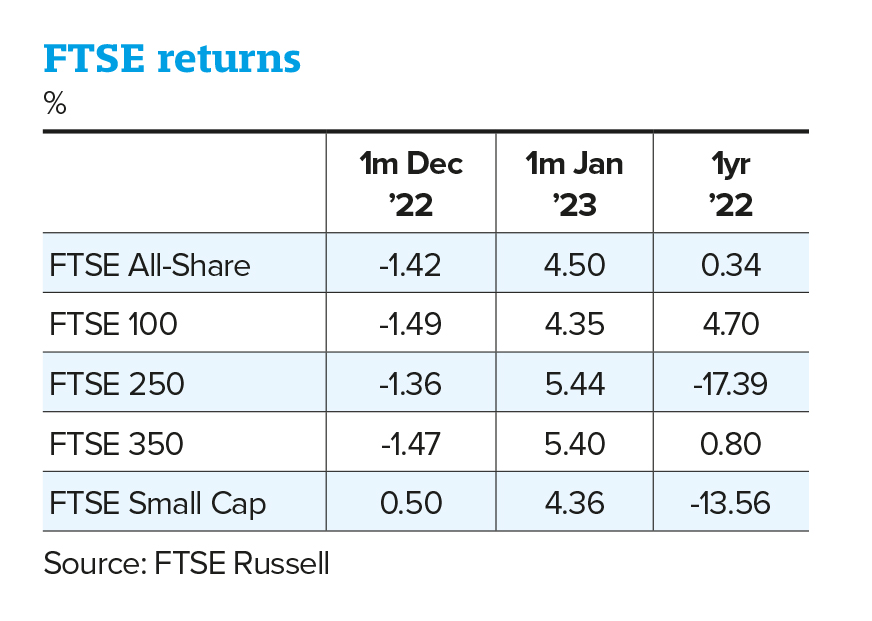

January proved unexpectedly upbeat for the FTSE 100, which closed the month up by over 4%. The early rally persevered, with the blue-chip index hitting a historical high and breaking through the 7,900-barrier on 3 February, surpassing the 7,877 points it recorded in May 2018.

The more domestically focused FTSE 250 endured greater volatility in 2022, troughing in October before staging something of a comeback in the closing months. It ended last year down more than 17%, while its big brother closed 2022 up nearly 5%. But January too has been kind to the FTSE 250, which was up 5.4% as February entered the fray.

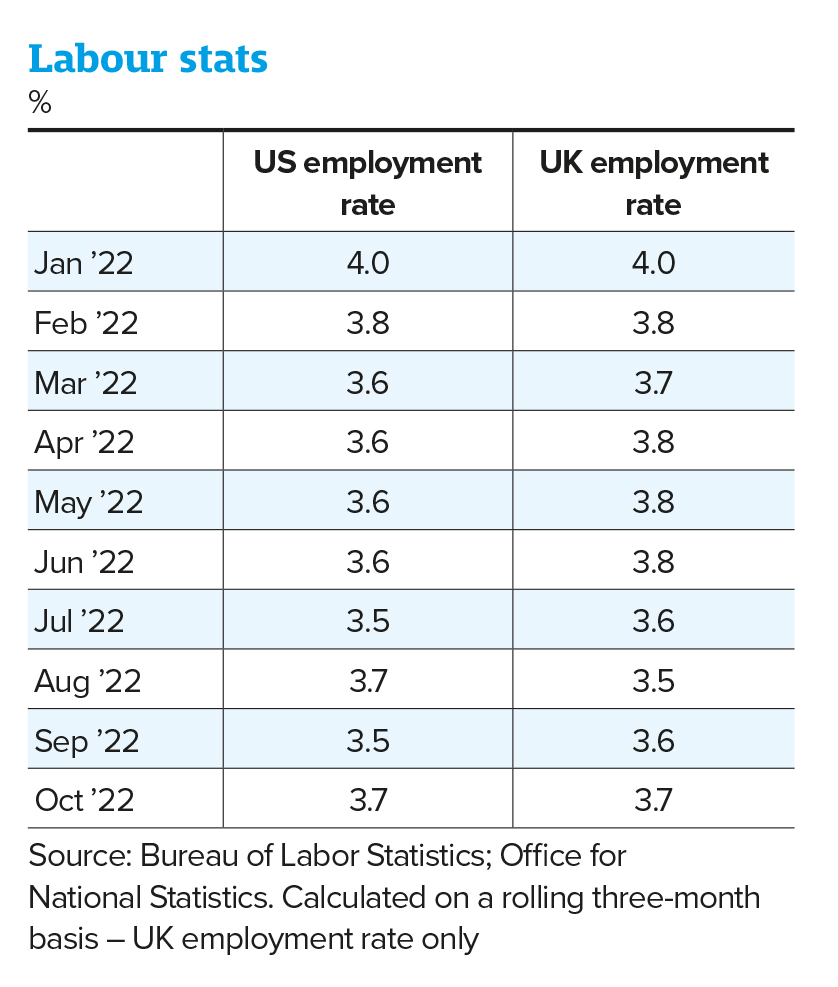

Another key indicator of recession is unemployment, and the latest data in both the US and the UK points to very tight labour markets. There are currently 0.6 candidates per vacancy in the US, while the UK ratio is closer to 1:1.

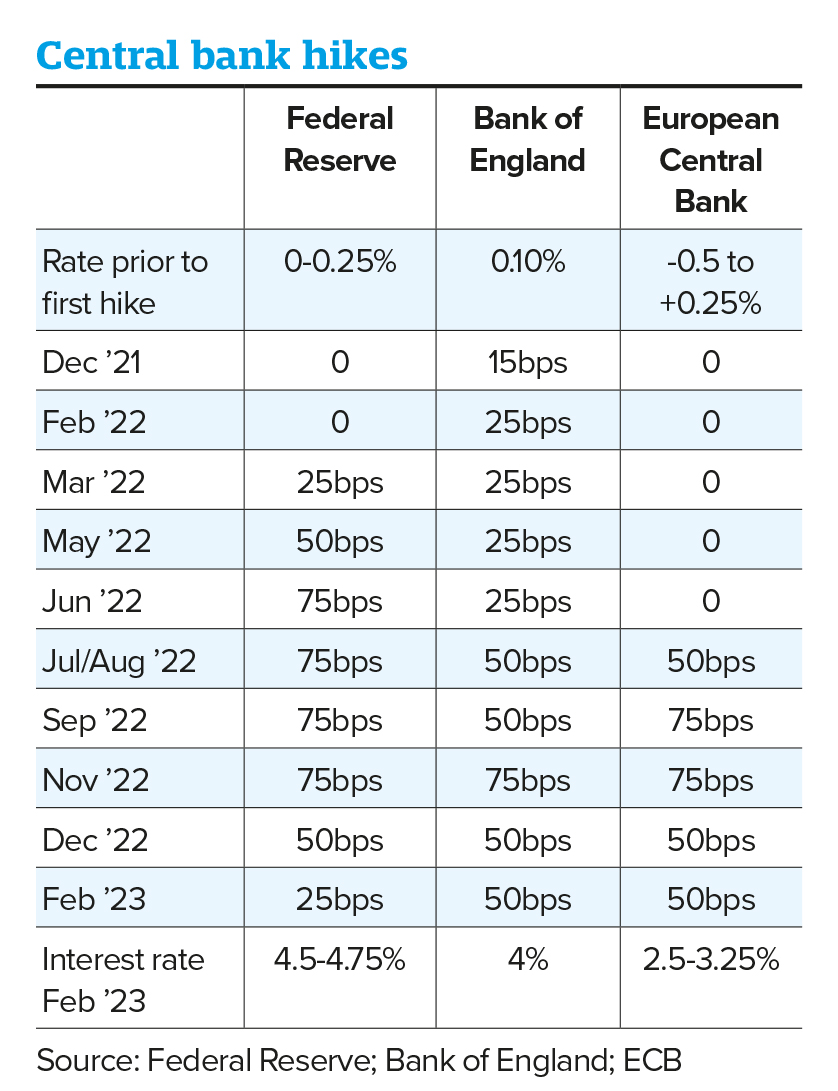

But the outlier casting the biggest shadow over the ‘will it/won’t it be a recession’ talk is central banks raising rates to fight inflation.

That battle pushed the Bank of England to make its first, albeit tentative, move in December 2021, taking the base rate from its historical low of 0.1% to 0.25%. The Federal Reserve followed suit in a more aggressive fashion in March 2022, with the European Central Bank waiting until July 2022 to join the party.

“We have never had rising rates going into a recession, or quantitative tightening,” says Ben Yearsley, investment director at Fairview Investing. “Every recession is different, and inflation is driving this one. I wouldn’t say it’s coming under control, but it is stabilising.”

At its peak, year-on-year headline inflation in the US was 9% in June 2022. It had fallen to 6.5% in December, down from 7.1% in November. The story in the UK is bleaker, with headline inflation having reached 11.1% in October 2022 before falling back to 10.5% by December.

During short, sharp recessions, as was the case with Covid-19, Darius McDermott, managing director of Chelsea Financial Services, says “central banks throw liquidity at the markets but they can’t do that this time because that leads to inflation, which is what we’re fighting”.

But, as pointed out by the IMF’s Georgieva, a true recession is not guaranteed. The third quarter of 2022 delivered negative GDP growth of 0.3% in the UK, and Yearsley thinks the small uplifts in October and November, combined with a December boost, means a technical recession is not on the cards.

Had the Queen’s funeral not taken place in September, it is unlikely GDP would have contracted in the third quarter. The extra bank holiday distorted the figures and resulted in a more positive Q4 than would otherwise have been expected, Yearsley explains.

As such, he expects Q1 2023 to deliver negative GDP growth, but not the second quarter of this year, which again means “we probably have avoided a technical recession of back-to-back quarters of negative growth”.

The coronation of King Charles III in May, which means another extra bank holiday, is unlikely to have a similar effect to his mother’s funeral, as “we’re going into summer and energy prices, on the back of the warmer-than-expected winter in Europe, won’t be such a factor”.

“We have probably missed a technical recession but, for all intents and purposes, we have been in one – it’s just the way the dates have fallen,” Yearsley adds.

“The central banks have all hiked, economies are slowing, inflation is falling back slightly –maybe not enough in some cases. But the medicine is working. I’m not as gloomy as probably a lot of people out there. Assuming there isn’t a massive cold spell coming in the next three months, we’ve been through the worst of winter. The economy is okay, it’s not brilliant but it’s not been disastrous,” Yearsley adds.

Inverted yield curve

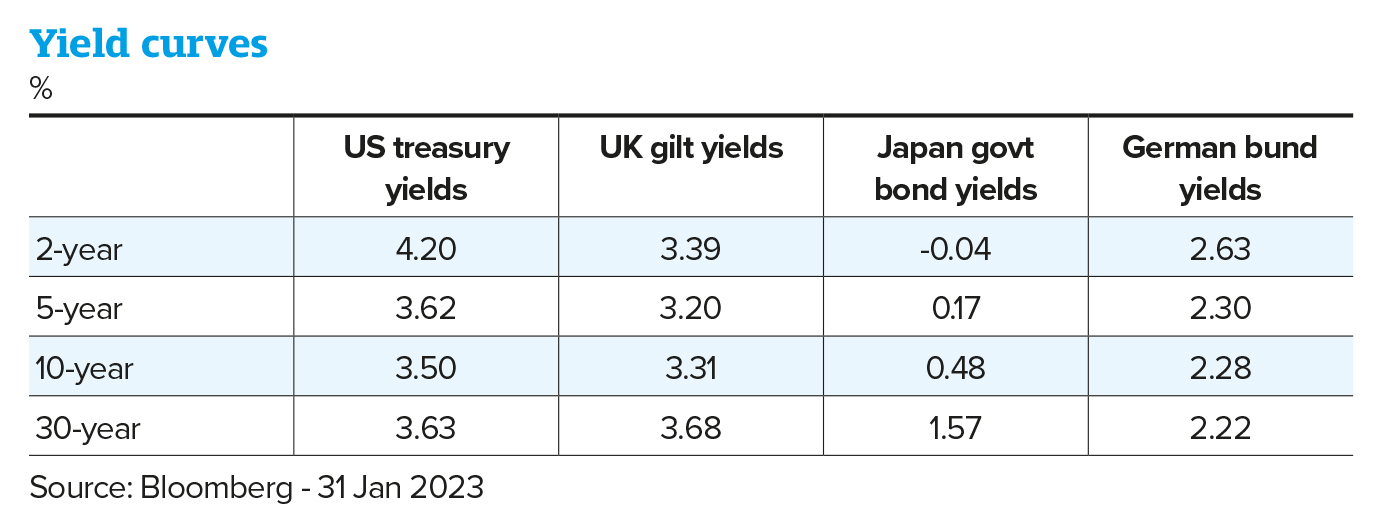

Looking specifically at the US, McDermott points to the inverted yield curve as a big flashing sign that recession is on its way – if not already here.

“It is a big leading indicator and has, in fact, predicted every recession since the 1960s. The yield curve has been inverted in the US for the majority of last year, but certainly the second half.” Yearsley concurs, describing it as “quite weird”, especially compared with “the quite flat” UK curve.

As for the US avoiding a downturn, McDermott is unconvinced. Given the more aggressive rate hikes by the Fed, he thinks they may get a shorter recession. “Interest rates generally have a 12- to 18-month lag, so that should now be starting to hit the economy.”

The US definition of a technical recession is only partly met with back-to-back quarters of negative growth, which it recorded in 2022 but an official recession was not declared.

The final decision lies in the hands of the National Bureau of Economic Research’s Business Cycle Dating Committee, which monitors peaks and troughs in markets and identifies if declines in economic activity are sector/region-specific.

Markets go rogue

Trying to predict what economic growth is going to look like is “a fool’s game”, says Justin Onuekwusi, Legal & General Investment Management’s head of retail investments Emea, because “the likelihood is you are going to be wrong”.

It’s for this reason that his team builds its portfolios around a base case but also incorporates a range of outcomes. “Our base case typically only has a weight of around 30%, so quite low, because we recognise there is a greater probability of us being wrong that being right.

“Ultimately, my portfolios have to be robust around a range of different outcomes.”

So, what does the current base case indicate? Onuekwusi says: “We do think there will be a global recession, and that Europe and the UK are in a worse position than the US, because the US has a sizeable consumer base to bail them out.”

There are caveats to that stance, he adds. Chief among them is the reopening of China and the growing significance of central banks, which are “more pivotal than they have ever been”.

“As they have become more transparent, we all analyse every single word that comes out from them.”

And it’s not just the reports that go under the microscope, the post-update interviews are also scrutinised by analysts.

“With greater technology, transparency and understanding of central banks I think the likelihood is a recession gets priced in very quickly, which is probably the new reality. If you looked at the different indicators at the end of last year, around 60% of a typical recession was already priced in.” Onuekwusi describes the current situation as “the best telegraphed recession since I’ve been managing money”.

But McDermott feels there is a disconnect. “You’ve got central banks telling you what they are going to do, but markets don’t believe them. The market is already pricing in cuts in the US in the second half of this year, even though chair Jerome Powell has said that’s not the plan. They are going to raise, stop and then pause. So, who’s right? Well, normally the market – but not always.”

What to do?

Given all the mixed signals and confusion, where does that leave investors?

“The 60/40 portfolio is no longer a dead parrot,” says Yearsley. “It was dead and buried last year but has mostly been resuscitated. I like bonds. On a risk/reward basis, if you can get between 6-8%, why shouldn’t you have bonds? In a recession you don’t want high yield, but I think high-quality investment-grade bonds look good at the moment.

“If we do get a deeper recession, central banks will have to cut rates and bonds will respond and go up in price. If it is a shallow recession, then rates have peaked anyway. Ignore the fact they are delivering less than inflation, that can’t be helped.”

He adds: “I have been a long-term believer in infrastructure, and I remain so. There is nothing wrong with ‘unexciting’ at the moment. Oil and gas companies as well, notwithstanding the threat of windfall taxes. I think Asia looks good, now that China has reopened – albeit rather haphazardly – that weight has finally lifted off Asia.

“There are a lot of good areas out there but bonds is the one I wouldn’t have said in the past five years. I haven’t liked them for a long time and reduced my allocation in late 2021 because prices were so silly. I’ve been buying back in since October 2022.” Yearsley smiles: “Dull, isn’t it? Bonds and infrastructure.”

Onuekwusi thinks 2023 “will probably be a turning point for the bond market and the way investors think about them”.

Where he is worried at the moment, however, is investors thinking about making a move up the risk spectrum on the back of their cautious portfolios performing poorly of late. “At exactly the wrong time a lot of investors are now starting to question whether they should holding as many bonds.

“Second, we know the best time to invest in an asset class is when you see extreme falls. Ultimately, people put too much weight on the base case.”

He adds: “The value of diversification and finding asset classes that can provide that went up significantly last year. One of the things we try to do is continue to find new asset classes that can provide true diversification in the multi-asset portfolio.”

That turned out to be infrastructure and commodities, which “were the big beneficiaries of last year”. “In the past six months we have been increasing our gilt exposure,” which Onuekwusi describes as “a huge benefit after the mini-budget”.

“We’re seeing our tech positions starting to come through this year and forestry has been a theme that has worked well for us. With China reopening, having a bias towards emerging markets has been positive for us.”

For McDermott, the mantra is balance. “It’s too early to be swinging the bat one way or the other. If you believe in a big recession, US rates will have to fall. Then you want duration because you make more money out of longer-dated bonds.”

He adds: “We’ve fairly dramatically increased our fixed-income weighting in the past six months, as they’ve now proven to offer a decent yield and some potential capital gains as well.”

Defensive assets are the name of the game if the recession is worse than expected, he adds: “I want some cash, as I can get to it quickly if markets do fall. Government bonds tend to do well in recession. But if I’m wrong and the markets bottomed in October last year and we’re off to the races again, then I still need some beta in my portfolio.”

It is a “heads we don’t win, tails we don’t lose” stance, McDermott says.

This article first appeared in the February edition of Portfolio Adviser Magazine