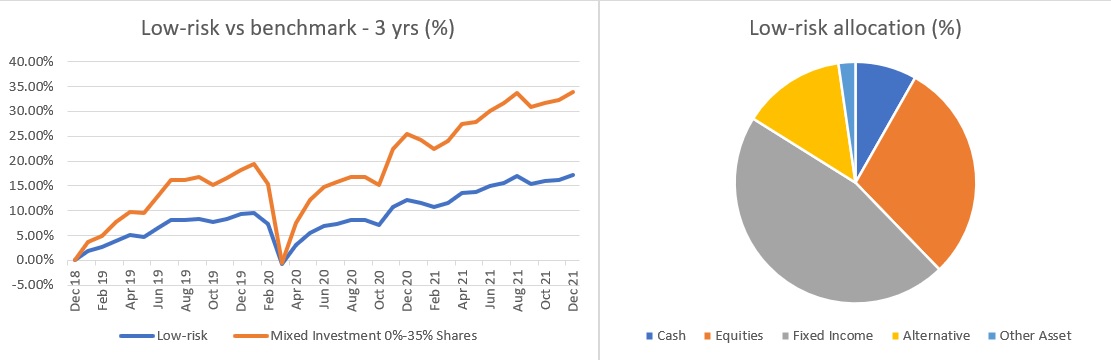

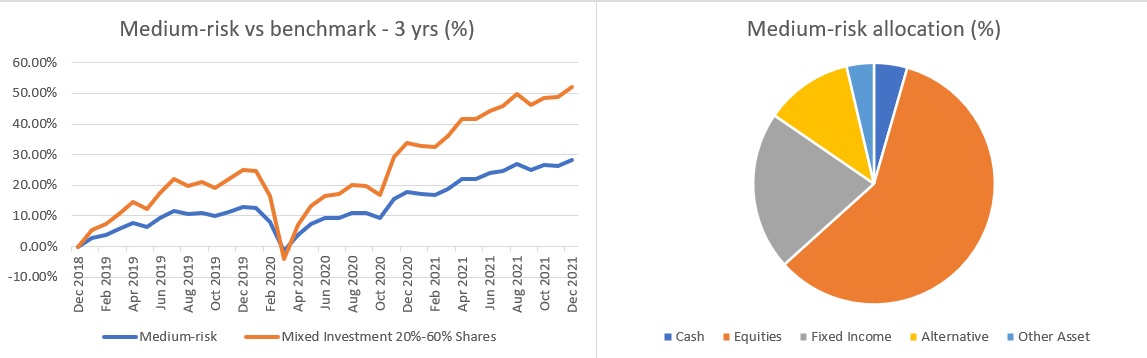

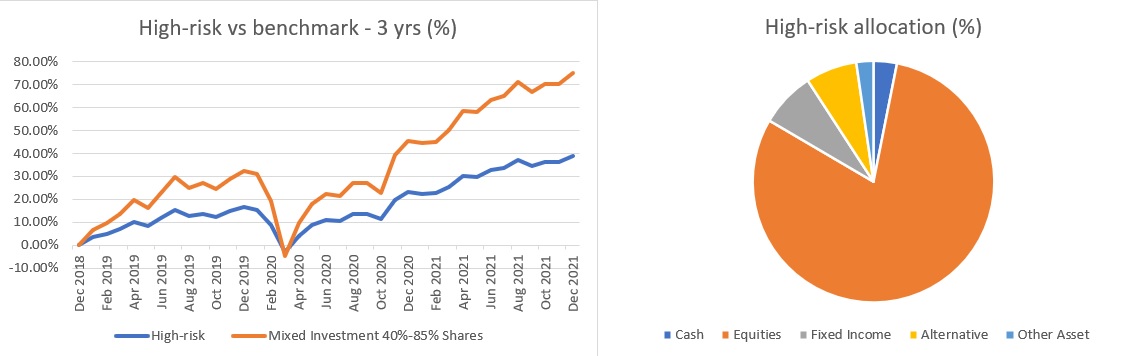

The final quarter of last year saw continued strong growth in client portfolios with low, medium and higher risk mandates turning in returns of 1.45%, 2.59% and 3.42%, respectively, writes James Hoare, managing director of Trustee MPI.

But the start of 2022 saw a significant reversal of fortunes, with concerns of interest rate rises and heightened tensions in Eastern Europe causing markets to retrench, particularly from growth stocks such as technology and consumer discretionary.

Whether this rotating is likely to persist well into the year remains a point of debate among managers; as Robert Alster, chief investment officer at Close Brothers Asset Management, explains: “At the start of 2022, we were not expecting the magnitude of the rotation out of ‘long duration’ equities, especially technology stocks.

“The debate has been very intense on whether this rotation will carry through 2022 or is this just profit-taking after a great run, and the fundamentals will re-assert themselves? We believe that it is the latter.”

The reason he gives is that the drivers of this rotation are likely to be short-lived: “We expect inflation to peak sometime around Easter as anniversary effects roll-off, and we see some supply chain issues begin to ease. That should allow bond yields to plateau or even fall and a general move back to growth-oriented names.”

Driven by base and pandemic effects

Inflation continued to weigh heavily on managers’ minds with just over half of those who responded to our survey rating it as a significant threat.

However, as UBS’s UK chief investment officer Caroline Simmons points out, the increase in inflation has been concentrated in a few key areas.

“Although US inflation is around 7%, 2% of that is due to energy and 1.5% is due to used car prices. Second-hand cars got very expensive because new car production almost stopped due to a shortage of microchips. Also, people were less willing to take public transport during the pandemic.”

However, she continues, most of these effects are transitory: “For us, inflation is very much driven by base effects and some pandemic effects that will, we believe, fade as we go through the course of this year. In addition, they [central banks and governments] will be pulling back on the monetary and fiscal stimulus this year which again should allow inflation to return down to more normal levels.”

This view was echoed by Alster, who believes that wage growth has been localised to certain sectors: “While we are seeing some wage inflation in certain areas of the market, for example, social care, we do not see it taking general hold.”

With oil prices increasing, money supply expanding and government spending rising, comparisons have been drawn to the 1970s. But Alster dismisses the suggestions that we’re entering a similar period of stagflation: “This doesn’t feel the same as the 70s when we descended into a wage/price spiral. Union power has substantially diminished, and technological advances enabling constant price comparisons will mean that wage pressures will moderate.”

Although what moderate means remains uncertain, as Simmons adds with a cautionary note: “Whether more normal means 3%, 4% or 5% will depend on how high wage growth goes. During the pandemic, a lot of people dropped out of the workforce. The assumption was that all those people would return to work post-pandemic, but they haven’t. The younger people are coming back, but the older people, for various reasons, are less so.”

That has clearly been a focus for central banks, she goes on to say, and what caused them to do their big pivots in December and into the start of this year: “The headline figure was not what worried them, it was that the labour market was going to be tighter than they initially thought. If wage growth gets entrenched at a higher level, that is obviously hard to undo.”

How central banks react to the data remains a concern amongst managers with over 70% of managers citing that a policy error by the central banks as a significant threat to client portfolios.

Striking a balance between inflation and growth as economies get back to some sort of normality will be the challenge as Alster explains: “We assume that the baton will be passed between worries about interest rates to more positive news on earnings and growth. In this scenario. you will get some volatility, but equities will continue to move up. However, if central banks do anything in terms of policy error that endanger that scenario, then there will be potential problems and increased volatility.”

This sentiment was echoed by Simmons who goes on to say that “central banks have a very difficult landscape to navigate so are not committing to too much. They are telling us they will be data dependent and will want to see the impact of each policy change before moving to the next”.

Opportunities

However, against this backdrop of rising rates and increased political tension opportunities exist, as Simmons explains: “We have had a preference for equities over fixed income for at least 18 months. Within that, we have a preference for value at the moment including Eurozone equities, global energy and financials. We also like global healthcare as a more defensive tilt.”

She goes on to explain; “Our decision to go into financials was predominantly because bond yields were rising. We wanted to have sectors that would benefit well in that environment and that points to financials as they earn greater net interest margins at higher yields. Also, valuations were cheap, and banks are quite cyclical, so they tend to do quite well in an environment where there is good [economic] growth.”

Also, the recent demand for goods, in particular cars has also presented other opportunities, as Alster explains: “We watch the auto supply chain for semiconductors quite closely because it’s more transparent. You’ve got the demand there; people want new cars. You can also see how the semiconductor manufacturers are reacting to that demand with capital investment. That provides an investment opportunity because semiconductor manufacturers have extraordinary pricing power at the moment.”

Another consistent theme amongst managers has been the healthcare sector which offers both short term defensive features, in pharmaceuticals, as well as longer-term growth opportunities, as Simmons explains: “We like the idea and the valuation of the pharma space to manage a bit of the volatility as the economic growth starts to slow as we go through the year. The other parts of healthcare are more cyclical, for example, health tech, biotech and generic therapies and these play into our longer-term views on demographic changes, especially in ageing populations. There are strong correlations between med-tech, for example, hip replacements, and the age of your population. There are also some short term benefits as we catch up post-pandemic and non-emergency procedures resume.”

According to our survey, around a third of managers stated that they were more cautious than this time last quarter with very few saying they had become increasingly optimistic. All eyes remain firmly on the trajectory of inflation and in particular the policy response to it.

Central banks, it seems, will need all their skill and judgement, to navigate us back to a more normal economic environment following the unprecedent events of the past two years.

The data below is provided by Trustee MPI:

This article was written for Portfolio Adviser by James Hoare, managing director of Trustee MPI.