Value managers have become a dying breed, their investment style come to be seen as toxic over a period of 10 years. Fund groups such as Baillie Gifford, Lindsell Train and Fundsmith Equity that have poured money into so-called quality growth companies have dominated performance tables and attracted billions of pounds into their funds.

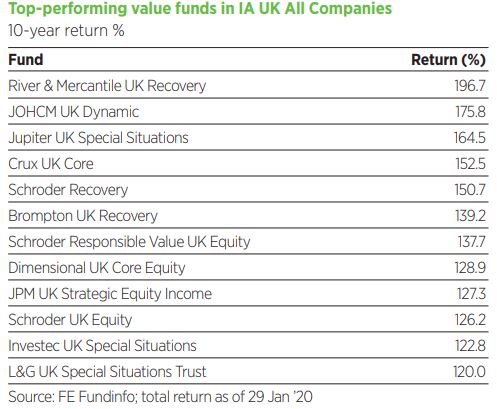

The top fund in the UK All Companies sector, Slater Growth, has returned 365.1% over the past 10 years, 164.9% more than the strongest-performing value fund, River & Mercantile UK Recovery, at 196.7%.

A Morningstar report from January last year revealed that 92% of global equities funds under management were growth-focused, compared with just 8% that were value-centric.

“The curious thing is 10 or 15 years ago, there used to be thousands of value managers,” says Seven Investment Management chief strategist Terence Moll. “These days, you get virtually no value managers.”

But more recently value has begun staging a comeback. From September 2019 to the end of January 2020, the MSCI UK Value Index has toppled MSCI UK Growth, climbing 5.2% as the other is down by 0.8%.

Value-centric funds such as Alastair Mundy’s Investec Special Situations and Henry Dixon’s (pictured) Man GLG Undervalued Assets strategies were back on top of the IA UK All Companies sector, while Nick Train’s Lindsell Train UK Equity Fund, one of the strongest performers of the past decade, was at the very bottom.

Closing the gap

Gary Potter, co-head of the BMO Gam multi-manager team, does not think quality growth’s slip-up in September was a blip and expects to see further underperformance from growthier managers.

“Nothing against Nick Train but he had a tough period, which he expected, by the way,” Potter said at a roundtable event at the beginning of January. And yet “everyone just keeps buying it on the basis they think he can repeat it but perhaps that’s not quite so likely”.

Willis Owen head of personal investing Adrian Lowcock says that while pure value managers have struggled in relative terms during the past decade, many have still made money in absolute terms.

Hugh Sergeant’s R&M UK Recovery, Alex Savvides’ JOHCM UK Dynamic and Ben Whitmore’s Jupiter UK Special Situations are all in the first-quartile of funds in the UK All Companies sector over a 10-year period.

The 12 strongest-performing value funds all did better than the MSCI UK Value Index, which returned 98.3% in sterling terms, while the top seven managed to beat the IA UK All Companies sector average (131.9%) and even the MSCI UK Growth (133%).

The gap between value and growth over 10 years is not as marked as people make it out to be, according to Chelsea Financial Services managing director Darius McDermott. “It shows you that even with a headwind, value managers can outperform.”

Recipe for value

But what is the recipe behind the success? Is it a case of style drift or is it the result of superior stockpicking abilities?

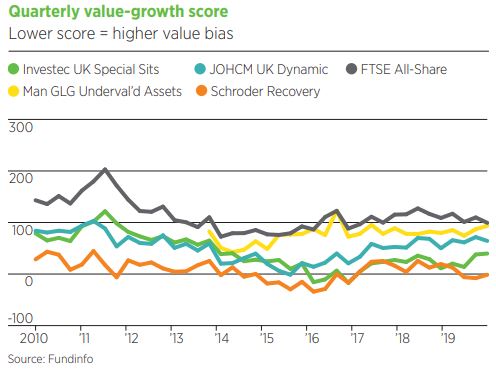

Morningstar conducted a quarterly growth/value analysis for Portfolio Adviser, comparing the styles of four funds traditionally billed as value against the FTSE AllShare. Funds that have a lower score have a higher value bias.

Since launching in Q4 2013, the Man GLG Undervalued Assets Fund scored consistently higher than the other funds in the sample: Schroder Recovery, Investec UK Special Situations and JOHCM UK Dynamic.

In Q4 2019, it had a score of 93.54, just shy of the FTSE All-Share’s 99.32. Schroder Recovery, run by duo Nick Kirrage and Kevin Murphy, clocked in at -1.31, while Mundy’s Investec UK Special Situations scored 39.79.

“The portfolio has a value tilt relative to UK All Companies peers but the process also steers the managers towards elements of quality (balance sheet) and positive earnings momentum,” says Morningstar senior research analyst Samuel Meakin.

This tendency has helped managers Dixon and Jack Barrat “overcome an overall value headwind, with stock selection the primary driver of active returns since this team moved to Man GLG”, he adds.

“The fact is that many funds are not run with a pure growth or pure value style,” says Lowcock. “There could be a number of reasons to hold a stock and it is possible for both a growth and a value manager to like the same company.”

According to McDermott, “healthy weightings” toward mid-caps, which have outperformed during the past decade, have also helped some value managers like Dixon and Barrat do better than expected despite their style being out of favour.

A third of the £1.4bn Man GLG Undervalued Assets Fund was invested in businesses with a market cap of between $2bn and $10bn, and 15% is held in companies valued between $250m and $2bn at the end of December 2019.

In relative terms, discount airline Ryanair is the fund’s top overweight, comprising 2.9% of the portfolio, followed by FTSE 250 residential property developer Bellway at 2.7%. It is underweight large-cap names such as Royal Dutch Shell, HSBC and Diageo, measured against the FTSE All-Share.

Similarly, Savvides’ JOHCM UK Dynamic Fund also has a third in mid-cap names, while Sergeant’s has 40% in smaller companies, compared with 32% in mega-caps valued at £20bn plus.

Dixon has been more “pragmatic” than other value managers, says McDermott, by buying stocks that are cheap but not necessarily the very cheapest. This is a far cry from Mundy “who doesn’t look at anything until it’s fallen at least 50%”, he adds.

Long and the short of it

Unsurprisingly, the ‘pure’ value managers have fared worse than value investors more amenable to finding opportunities across the cap spectrum.

According to Meakin, while Mundy’s longer-term performance has been strong, he has been “less than impressive” over the medium term.

“As well as facing a style headwind, a significant factor was the high- and near-cash position resulting from a lack of compelling new ideas being generated, causing the strategy to lag behind in some of the strong equity rallies,” he says.

“However, there have been additions to the portfolio during the past couple of years that have gradually reduced this position and therefore its impact on returns,” adds Meakin. “Indeed, this helped the fund enjoy strong relative performance in 2019, particularly in the latter part of the year, which provided a market environment more conducive to the fund’s approach.”

Stick to your knitting

Kirrage and Murphy’s Schroder Recovery Fund has had a more challenging time pulling ahead. Even looking over the five months since the growth sell-off last September, the fund is still in the third-quartile of the UK All Companies sector.

The fund has trailed both growth and more value-orientated funds over one, three and five years.

Meakin describes it as “one of the purest exposures to the value style in the market”. “The managers are not constrained by the FTSE All-Share benchmark when constructing portfolios but have consistently stuck to their knitting in terms of seeking out value opportunities.”

Lowcock highlights Schroder Recovery as one of the funds he likes best.

“This is a deep value strategy and the managers seek to identify companies that are trading at significant discounts to their perceived fair values, starting with a number of valuation screens,” he says.

“Price relative to 10-year average earnings – cyclically adjusted price/earnings – is a key screen but they also look at other metrics, including price/tangible assets.”