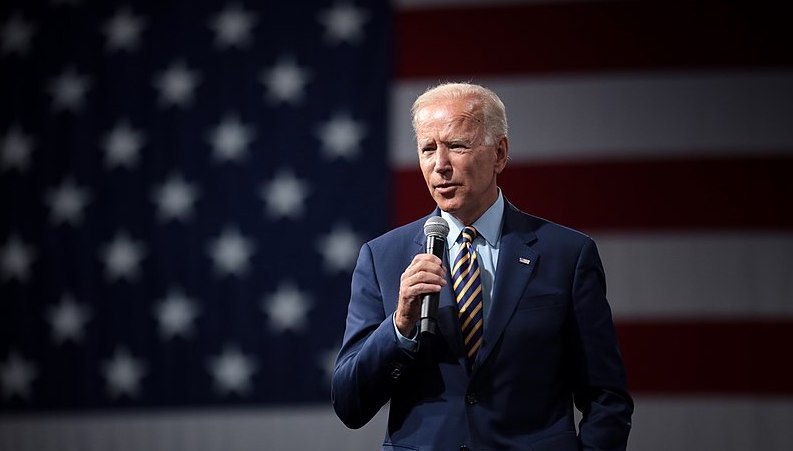

Discretionary fund managers have raised concerns that Boris Johnson’s approach to Brexit risks alienating incoming US president Joe Biden with negative consequences for UK assets.

News of Biden’s victory coupled with promising trial results of Pfizer’s Covid vaccine has already spurred on a global equity rally this week, with the FTSE 100 up over 6% since Monday.

But possibilities for tension between Biden and Johnson lie on the horizon due to the fate of Northern Ireland after Brexit.

“It’s hard to dispute that Britain without Brexit would be a much better starting point for the Biden/Johnson relationship,” says Psigma Investment Management head of investment strategy Rory McPherson.

“Making an enemy of the US – or at least failing to remain a friend of them – would likely be disastrous for the UK and UK assets and see the index drift further into global obscurity,” warns McPherson.

Despite the UK government’s Internal Market Bill suffering a defeat in the House of Lords on Monday evening, Johnson has vowed to press ahead with the bill, which would allow the country to renege on its international obligations under the Brexit withdrawal agreement, when it returns to the House of Commons in December.

In contrast, Biden has warned the Good Friday Agreement must not become a “casualty of Brexit”. In September, he tweeted: “Any trade deal between the US and UK must be contingent upon respect for the Agreement and preventing the return of a hard border. Period.”

“Johnson does seem to be on thin ice in what he’s trying to do politically,” says Square Mile investment director Jason Broomer.

“Clearly the Irish remain an important constituency for US politicians and Biden is not willing to see the applecart be upset. Ripping up the Good Friday Agreement would be a definite no-no.”

See also: DFMs had already shunned UK ahead of record GDP plummet

Biden could ignite UK value recovery if Johnson plays ball

McPherson says a Biden presidency, which is built around higher stimulus and building bridges outside the US, should trigger a broadening out of the equity rally, shifting the focus away from the mega-cap growth names that have driven most of the performance growth. This would help the cheap and cyclically-biased UK stock market, he says.

UK equity funds have racked up £734m of net redemptions so far this year, according to Investment Association data, proving even less popular than European equity funds, which have seen £595m in outflows.

But McPherson points out that there has been a renewed interest in British businesses from foreign buyers, with William Hill and Royal Sun Alliance both in talks for takeover deals, due to their relative cheapness.

“To some extent, the presidential result doesn’t matter for UK assets due to their cheapness and there’s a strong argument for Biden actually helping ignite a catalyst to ignite their recovery via harmonious trade deals globally,” McPherson says.

“However, this thesis very much hinges on a harmonious relationship between Johnson and Biden, with the ball being firmly in Boris’ court,” he adds.

See also: Beaten down FTSE stocks jump up to 40% on promising Pfizer vaccine

Canaccord Genuity Wealth Management CIO Michel Perera says a Biden bump could benefit the UK in a “roundabout way” but says the wealth manager is keeping its underweight to the asset class.

“Over the last four years, I’ve lost track of the number of times that people have told me that the UK market is the cheapest in the world and therefore at some point, it has to go up,” says Perera. “I’m glad we didn’t fall for that because it’s still cheap, and it’s actually cheaper.”

Even despite the recent stock market surge, the FTSE 100 is still down 16% year-to-date, Perera notes, while the S&P 500 and Nikkei 225 are up nearly 10% and the Shenzhen Composite is up an impressive 26%.

Perera says there needs to be a catalyst to spark a recovery in UK stock prices but he doubts removing the Brexit uncertainty is it.

“I’m not sure what that catalyst is,” he admits, “because frankly, the government has not covered itself in glory over the last year, whether it’s discussions on Brexit or how to manage the economy or how to manage Covid. And on top of that the [UK] sectors are not terribly exciting.”

Even if a US/UK trade deal is struck it could take as long as 10 years before it materialises, he says.

“To me, a UK/US trade agreement is a very, very long-winded, and probably even long-shot affair. I know that quite a lot of Brexiteers were saying, ‘Oh we can sign a trade agreement with America in six months or something’. It’s ridiculous.”

Expect ‘there is more that unites us than divides us soundbites’ from PM

Anthony Willis, investment manager in BMO Global Asset Management’s multi-manager team, thinks Biden and Johnson will be pragmatic enough to work through their differences, despite their opposing ideological views on Brexit.

“We expect more of the ‘there is more that unites us than divides us’ type soundbites,” he says.

In his tweet congratulating Joe Biden, Johnson emphasised the US and UK’s shared priorities on climate change and trade security.

“All the same, the UK’s exit from the EU means that the UK will not be seen as the conduit for US-EU relations that it was in the past,” Willis says, “which means the White House will likely seek to strengthen ties with France and Germany – as well as Ireland given President-elect Biden’s family connections.”

Deal with Biden hinges on Brexit outcome

Esty Dwek, head of global market strategy at Natixis Investment Solutions, says a UK/US trade deal will be contingent on the UK reaching a deal with the European Union.

If the UK crashes out with no-deal at the end of the year, it will be much harder for it to secure deals with other countries, she says. “It would absolutely be very complicated if the UK were to revert to WTO rules,” Dwek says. “It would lose a lot of its competitiveness”.

The UK is going to need deals with all the major economies, she thinks, but with Europe, its largest trading partner, most of all.

Willis agrees securing a deal with the EU is a bigger priority.

“The lack of an EU trade deal will be far more damaging given that we have been in the single market for decades and while a trade deal won’t replace that it will soften the blow,” Willis says.

“We don’t have a trade deal with the US already so if talks break down it means the potential boost from lower trade barriers will be foregone but it is not the same as the EU relationship where we are going from frictionless trade within the single market to potentially no deal at all.”

How badly does the UK need a US trade deal?

BNY Mellon Investment Management chief economist Shamik Dhar says while a trade deal with the US would be “symbolically important, its economic benefits are likely to be small” at least in the short-term.

US-UK bilateral trade amounts to around £100bn ($130bn), Dhar notes, which is larger than Britain’s bilateral trade with any individual EU country, including Germany, but pales in comparison to the £600bn worth of goods exchanged between the UK and the EU.

“£100 billion is around 5% of UK GDP, so boosting bilateral trade with the US by around 10% (a reasonable estimate of the impact of a trade deal) could be ‘worth’ around half a percent of GDP,” he says.

“While that might add to consumer welfare – by expanding choice and lowering costs – the direct impact on GDP would be smaller, since both imports and exports would rise.”