A combination of huge fiscal stimulus in reaction to the coronavirus pandemic and pent-up demand as economies emerge from lockdowns has the potential to cause a short-term inflationary spike, and spooked fund buyers are preparing their portfolios accordingly.

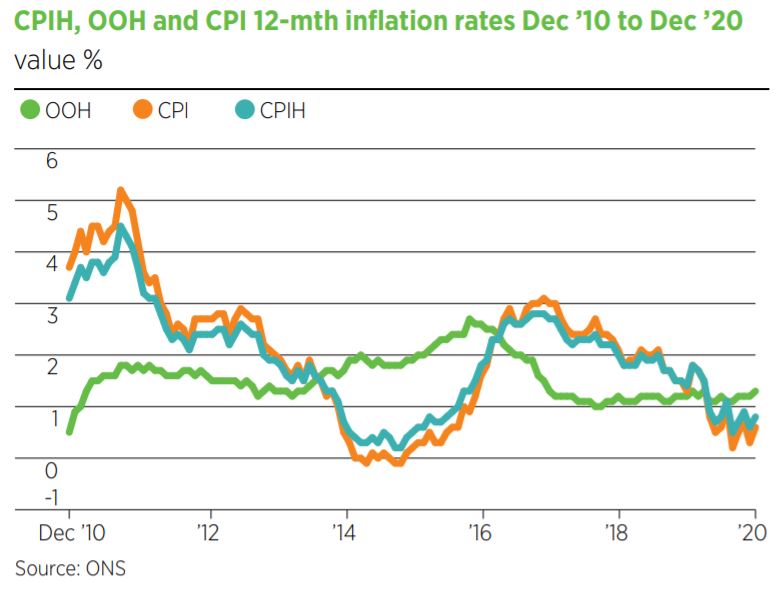

Inflation seems to be contained for now but there is increasing concern it could rise once social restrictions are lifted and suppressed consumer demand is let loose. Office for National Statistics figures put the UK Consumer Prices Index (CPI) at 0.7% in January, up from 0.6% in December and 0.3% in November, and although still a way off the Bank of England’s 2% target, consensus is that for inflation: the only way is up.

In the eurozone, headline CPI hit an 11-month high of 0.9% in January, up from -0.3% in December, although commentators were quick to point out the jump was due to one-off factors, including the addition of certain taxes that will fall out of the reading and a change in the basket of goods used to calculate the measure.

As well as bottled-up consumer demand, investors point to central bank stimulus, helicopter money from the government and the country’s savings ratio hitting fresh highs during lockdown as contributing factors to a potential bump in consumer prices in the year ahead.

Wealth managers recognised the signs early on and Iboss investment director Chris Metcalfe recently announced he would be making changes to the firm’s fixed-income holdings and cash position to prepare for what he describes as “the most inflationary environment we’ve had for years”.

Last month, a position to Blackrock’s Gold and General Fund was added to Smith & Williamson Investment Management’s managed portfolio service (MPS), in anticipation of resurgent inflation during the next few years.

Smith & Williamson MPS co-manager James Burns says inflation was effectively off the table for much of 2020, as the impact of the pandemic and subsequent lockdowns meant many drivers of inflation went into reverse. But he believes the outlook has changed.

“The key driver of this view is the outsized impact of policy, particularly the deployment of fiscal measures on top of the monetary stimulus that has been repeatedly used over the past decade,” he says. “We believe tail-risks of significant inflation may also be tilted to the upside, with the risk that policymakers are potentially building up more significant challenges in the longer-term and that the reaction function of central banks and governments might well be too slow.”

Temporary spike?

Psigma Investment Management head of investment strategy Rory McPherson says the firm’s base case is for an inflationary spike this summer that will wane fairly quickly before re-asserting itself again next year.

“This is likely to be most acutely felt in the May inflation numbers when we get the impact of the negative oil futures prices we saw in April 2020, when oil dropped to almost -$40 a barrel, as well as the weak currency impact from sterling in April 2020 feeding through into the numbers,” he says.

McPherson predicts this will be a temporary spike, however, falling back as economies remain partially closed. But beyond that there is a strong case for inflation rising and staying above target levels for some time once economies finally emerge from the pandemic.

“Key drivers of this would be the 24% year-on-year increase in the money supply which we’ve seen in the last year, huge amounts of pent-up demand and a willingness from central bankers to tolerate inflation levels that run above target, such as the US Fed’s new average-inflation-targeting framework,” he says.

Independent investment consultant Thomas Wells also thinks higher inflation is inevitable and that prudent investors should be planning for it now.

“As economies recover from the Covid-19 crisis, it would be naïve to expect governments with a new taste for fiscal expansion to rein in their spending,” he says. “Indeed, populist politics will get in the way of any attempt to put the fiscal genie back in its bottle.”

When it comes to monetary policy, Wells reckons it is highly unlikely that central banks will want to raise rates anytime soon. He notes that ordinarily, increased government spending would lead to higher interest rates but with central banks engaged in “quantitative easing (QE) infinity”, interest rates are likely to stay artificially low.

“Unlike the past decade of asset price inflation, we are set to see real-world inflation,” he adds. “This collusion between central banks and governments will result in our money being debased. Suppliers of goods and services, reacting to this debasement, will demand higher prices.

“As an investor, you should prepare for a painful period of financial repression, or what Russell Napier describes as ‘stealing money from old people slowly’.”

AJ Bell financial analyst Laith Khalaf also notes that while monetarist economic theory tells us that the huge increase in money supply will deliver inflation, “this is a dog that didn’t bark” after central banks embarked on quantitative easing following the financial crisis.

“Today however, loose monetary policy is combined with fiscal stimulus, and could be turbocharged by the prospect of consumers making up for lost time when social restrictions are eased,” he says. “So, there is some reason to believe this time really is different.”

Deflationary pressure

Khalaf also notes there are deflationary forces in the market, in particular unemployment is set to rise, while long-term secular trends, including technological advances and an ageing population, continue to weigh down on price rises.

“A stronger pound also helps in the short term to mitigate rises in imports, most notably for fuel, priced in dollars.”

Fairview Investing consultant Gavin Haynes thinks there is potential for inflation to spike but the uncertainty of the economic environment means it is impossible to predict whether inflationary or deflationary forces will dominate. But he does accept the presence of structural deflationary pressures that could easily lead to a deflationary backdrop in the western developed economies.

“The ageing population in the US and Europe – which is 10 years behind Japan – will result in less consumption, and the UK consumer makes up 70% of GDP,” he says. “The increasing adoption of technology is also deflationary, while there remains significant capacity in the economy and the negative effects of Covid are likely to have a sustained drag on economic activity.”

McPherson agrees it pays to be mindful of deflationary forces, including demographics, debt and productivity, which have held inflation down for a long time, and failure of central banks to create above-target inflation in the past decade.

“On this basis, we still maintain that a balanced and diversified approach makes best sense, but we are taking the opportunity to gradually tilt towards the more reflationary parts of the market,” he says.

Wells says an ageing population, increased debt that requires servicing and continued advances in technology making workers redundant are not usually the ingredients for higher inflation. “In fact, left to the invisible hand of free markets, the spectre of deflation that haunts developed market central bankers would make itself felt,” he says.

“It is this prospect of Japanification that gives our central bankers the zeal to pursue QE infinity. Unfortunately, given the combination of fiscal expansion and QE infinity, I expect the lax attitude of our central bankers towards sustained higher inflation to prove misguided.”

Inflation-proofing portfolios

Psigma has direct and indirect inflation hedges in its portfolios, which it is expects would do well in this environment.

“On the direct side, we have short-dated inflation-linked bonds and real assets such as commodities, infrastructure and gold equities,” says McPherson. “On the indirect side we hold investments in credits such as mortgage-backed debt, emerging debt and Asian credit, as well as meaningful allocations to Asian and emerging equities. These would likely benefit from a reflationary pulse.”

Haynes says while he’s not yet a full-blown convert to the ‘return to 1970s inflation’ thesis, given the US central bank has indicated it is happy to allow the economy to run hot, it makes sense to have inflationary hedges in place.

“Within equity exposure it seems a good time to be adding more value focused areas,” he says. “I would still tilt equity portfolios towards companies that can provide sustainable returns in a low-growth environment, however.”

With real interest rates likely to remain negative and central banks continuing to print money, Haynes, like Smith & Williamson, sees gold as a sensible diversifier. Within bond portfolios, he says having a barbell approach makes sense, between short-duration high yield, which would be less affected by inflation, and high-quality government bonds, to provide insurance if deflationary forces emerge.

“But as bonds continue to offer miserly returns, diversifying exposure into real assets such as infrastructure and property that can offer inflation protection also makes sense.”

He adds: “If structural inflation did lead to banks having to raise rates aggressively it would be hard to find anywhere to hide.”

Iboss investment manager Chris Rush recently told Portfolio Adviser that holding short-duration fixed income means little interest rate risk and therefore it should be more suitable to an inflationary shock. The firm has also reduced its treasuries and gilt positions and moved into strategic bond managers with longer track records and which have outperformed in multiple market conditions.

“These managers have a wide range of assets they can pick from, including sovereigns and index-linked bonds,” he says. “If you look over history, whenever inflation appears it tends to be sudden, sharp and without much warning. You need managers who can respond to that relatively quickly outside of the short-duration positions we already have.”

Wells notes wealth destruction from higher inflation is not limited to bond investors as equities also struggle in such an environment. His preference is to favour shorter-dated bonds, asset-heavy equities and real assets – “the asset class losers of the past decade”.

In Wells’ portfolio, therefore, defensive assets include cash, shorter-dated US treasuries, inflation-protected securities and gold. Growth, meanwhile, is skewed away from the US to the rest of the world, with an overweight in Asian and Japanese equities. From a sector perspective, Wells is bullish on banks, energy and gold miners.

This article first appeared in the February 2021 issue of Portfolio Adviser magazine. Read more here.