It seems a touch absurd to have focussed our January magazine’s cover story on food after so many people undoubtedly over-indulged during the festive break, but I suspect it will be one of the hottest topics of 2023.

Most people buy their goods without giving much thought to how it got from the field to the freezer section of the supermarket. It is a process that has been hugely sanitised. When people do talk about food production the conversation tends to focus on climate change, and for good reason.

A December 2021 UK government report concluded that domestic wheat yields fell by 40% in 2020 due to a combination of heavy rain followed by drought. That same report states that the UK is largely self-sufficient when it comes to producing grains, harvesting the equivalent of more than 100% of the oats and barley we consume. When it comes to wheat, we grow over 90% of what we use.

But a 40% reduction in yield suddenly makes us more dependent on imports. Anybody with a wheat allergy knows how ubiquitous an ingredient it is. If global production is unaffected, prices remain relatively stable. But what about when the global supply is affected?

Empty breadbasket

When Russian troops crossed the border into Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the invasion was the catalyst for a series of shocks that will impact on food production into 2023 and beyond.

Few in the west would have been aware of quite how much food in the global supply chain is grown in that part of the world. But the war has ravaged huge swathes of Ukraine, with land bombarded and crops set ablaze. Agricultural workers responsible for planting and tending to the next harvest have been conscripted into the army, many tragically losing their lives.

In a bitterly ironic twist, 2022 was a bumper year for Russian wheat. While the post-invasion sanctions did not affect food exports, getting the crop out through the blockaded Black Sea ports has been problematic for both nations. And wheat is only one example, Ukraine is also one of the world’s biggest producers of sunflowers, which has put a considerable dent in the edible oil supply.

While the instinct in the UK may be to take comfort in our levels of domestic production and alternatives such as rapeseed oil, the export issues impacting Russian goods goes above and beyond food stuffs.

Alongside the dawning realisation of how much food Ukraine produces for the world came the equally startling insight about how reliant farmers are on the supply of fertilisers from Russia.

“The effects of the Russia-Ukraine war may reverberate through the global fertiliser industry for years to come,” warns an S&P Global report. “Post-Covid supply-chain disruptions had already pushed fertiliser prices to cyclical highs in 2021. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, and the sanctions and trade supply disruptions that followed, then pushed prices even higher.”

It adds: “Russia is a major producer of the three main types of fertilisers – nitrogen, phosphate and potash, and a major exporter of key raw materials for fertiliser production elsewhere in the world.”

In early December, the BBC reported that the National Farmers’ Union (NFU) was warning the UK “is sleepwalking into a food supply crisis”.

The government claims the UK has “a highly resilient food supply chain”, but the NFU says energy-intensive crops such as tomatoes, cucumbers and pears will hit their lowest yield levels since records began in 1985. A pint of milk is meanwhile set to fall below the price of production and beef farmers are considering reducing the size of their herds.

According to the union, the rising cost of fertiliser, feed and diesel are to blame.

Hot and dry conditions

But the war was not the first domino to fall, according to Barings investment manager James Govan, who winds the clock further back to the emergence of a regular oceanic and atmospheric phenomenon at the start of 2021.

“La Niña basically created hot and dry weather in southern parts of Brazil and northern parts of Argentina,” says the co-manager of the Barings Global Agriculture Fund. “Brazil is the biggest soybean exporter in the world and the second biggest in corn, so that led to a disappointing harvest at the start of last year.

“And we are still living through La Niña weather conditions, continuing through the start of 2023,”

Govan adds. “It doesn’t impact us much here in the UK and Europe, but the effects are felt in places such as southeast Asia, Australia, South America and even the US.”

As a result of myriad weather and supply chain difficulties, “global grain inventories, excluding China, are at their lowest levels in more than a quarter of a century”.

“Inventories are low, but we are not expecting food shortages, especially in this country,” says Govan.

“We should have high grain and edible oil prices for at least two years. If you look at the futures curve on commodities it indicates at least two years of good pricing to get us back to more comfortable levels.”

And that would require a minimum of back-to-back global bumper harvests, he says.

Another gremlin in the food-price inflation machine is when countries feel they have no choice but to take protectionist measures to dampen both local inflation and local unrest. Recent examples include Indonesia temporarily restricting the export of palm oil and India doing the same with rice.

“Unfortunately, we have begun to see pockets of protectionism,” says Govan. “Indonesia is the biggest palm oil exporter in the world and the month-long restriction on exports had a material impact and increased volatility. The price of palm oil shot up on the back of the restrictions. After they were largely removed, that led to an oversupplied market for two or three months.”

Govan adds: “So, yes, things are tight. It’s not super acute but prices will remain high. It’s not quite stacking tins in cupboards time, but inventories are lower than comfortable levels.”

Inflation duration

Amid a cost-of-living crisis, paying more for food is the last thing anyone needs. The latest CPI figures show a cooling in the inflation rate, which was 10.7% in the year to November 2022, down from 11.1% in the 12 months to October.

The largest downward contribution between October and November “came from transport, particularly motor fuels, with rising prices in restaurants, cafes and pubs making the largest, partially offsetting, upward contribution”, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

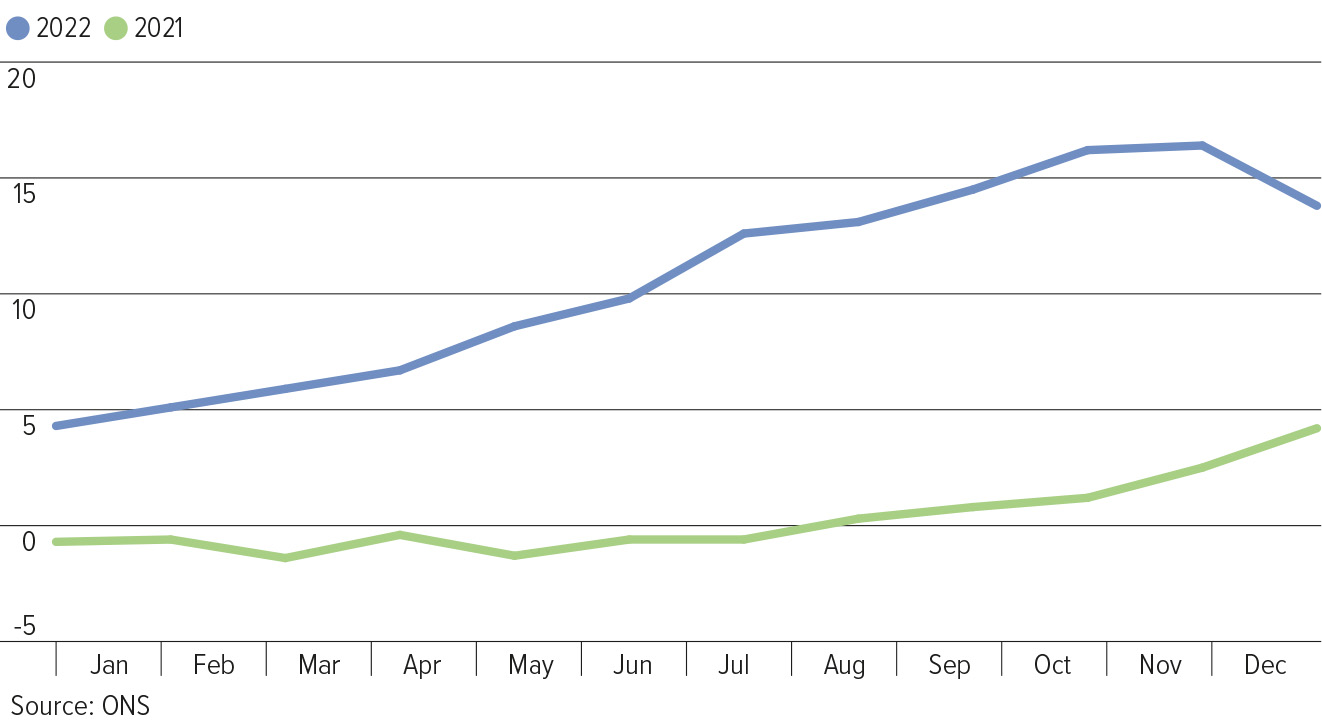

Year-on-year inflation rates: 2021 versus 2022

But, after housing and housing services, food and non-alcoholic beverages was the second-biggest component of CPI – increasing to 16.4% from 16.2% in October. In November 2022, food inflation hit its highest level since at least 1977, according to the ONS. The largest upward effect came from breads and cereals, partially offset by a small downward effect from fruit.

It was interesting, however, just how few industry commentators chose to mention food in the views they shared with the market. Among those who did was Axa Investment Managers’ economist Modupe Adegbembo, who wrote: “Food inflation also picked up again in November, marking 16 consecutive months of rises.”

“Shopping for food is taking a bigger bite out of household budgets,” notes Myron Jobson, senior personal finance analyst at Interactive Investor. “Part of what is fuelling this are price jumps in everyday larder products, such as bread, which makes this type of inflation sticky because consumers are resigned to paying it as they form part of essential expenditure for many.”

But Melanie Baker, senior economist at Royal London Asset Management, says what caught the attention of industry commentators and economists was the surprise fall in inflation. “Food wasn’t part of that particular story, as it increased about 1% on the month, pretty similar to the increase we saw this time last year.”

And it is that focus on annual rather than monthly change that is important, Baker says. “In that first year, you have really significant jumps and big increases in inflation. But after 12 months, even if pricing is still at that really high level, year-on-year inflation technically drops to zero.”

She is expecting inflation to come down “quite substantially” in 2023, but a large part of that will likely come from energy prices. “If we don’t see the same scale of price increases this year that we saw last year, that will really start bringing the overall level of inflation down.”

Baker adds: “The big uncertainty for economists and central banks is what is going to happen to the core services that are more reflective of underlying domestic inflation, so things like wages.”

Investing in ‘better’ food

Circling back to agriculture, Barings’ Govan expects the average price of grains and edible oil, “assuming the harvest is as expected”, will be lower in 2023 “because we are unlikely to get the same price jump from when Russia invaded Ukraine”.

While punchy by historical standards, in light of low inventory levels, he predicts prices will not be as high as 2022.

Whereas farmers in certain sectors, such as those mentioned above, are struggling with costs, Govan says the higher prices have benefited food producers more generally.

“The US Department of Agriculture expects US farmer profitability, on an inflation adjusted basis, to be the highest since records began in 1929. There are always exceptions, and potentially some bad luck if the weather is not very good, but economically 2022 was a good year to be a farmer, particularly on the arable side.”

And that is expected to continue in 2023.

These additional profits have also given farmers firepower to improve their machinery and deploy more modern technological advancements to the betterment of the produce and the land. As such, from a fund perspective, Govan says “the outlook is positive for the agriculture equity asset class”.

“The technology side is getting better,” he adds. “We have more drought-resistant seeds, the ability to track the weather and determine optimum planting conditions, more targeted use of water, fertilisers and pesticides. There are lots of interesting and exciting technologies that make this sector more resilient and robust, and which can drive productivity.

“Yes, weather patterns, like La Niña or El Niño, can certainly be challenging. But that means we need to keep investing in the technologies which help us to better withstand that.”

This article first appeared in the January edition of Portfolio Adviser Magazine