By Richard Scrope, manager of the VT Tyndall Global Select fund

Fifteen years is a long time in the world of fund management. When I took the reins of the Global Select fund in 2008, the market was in despair, being only a month after the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

In retrospect, it could hardly have been a better time to be given a blank canvas from which to build a portfolio of quality global companies, and stocks in which I invested at that time still represent one quarter of my current portfolio.

Fifteen years may seem a long time to remain invested in a company, certainly by today’s standards where the average investor holding period stands at less than six months. There has been a growing trend to seek short-term gains and to sell at the slightest sign of bad news.

This propensity to overreact to short-term price movements, can be a boon to long-term investors, allowing them to step in and buy at prices that are dislocated from the long-term fundamentals.

This has been further accentuated by the rise in high frequency trading (HFT), programme trades and other computer driven models estimated as accounting for 40% of all market volumes today, these trades look to make money by having a nano-second advantage in capturing data over the rest of the market, moving in and out of investments with equal speed.

Programme trades have little regard to investing in company fundamentals and the value of its future cash flows. Algorithms programmed to act as stop-losses can lead to panic selling, increasing volatility, and in extremities, leading to incidents such as the flash crashes of 2010 and 2015.

Related to this is the rise of passive vehicles and ETFs. These represented around 17% of the US market 15 years ago, compared to around 33% today, a percentage which many expect to continue to increase.

These funds are truly valuation insensitive as they buy and sell at any price, depending on orders. What is problematic about these funds is that they often have similar underlying holdings despite tracking wildly different factors.

This has led to extreme narrowness in global markets as the greater the weight in the index, the greater that amount of the company a passive fund must buy regardless of weight. As the most common form of passive funds are designed to track indices based on market capitalisation the biggest companies globally get bigger and the smaller, smaller.

Another trend over the past 15 years is digitalisation and the rise the mega-cap technology stocks. These have driven the considerable outperformance of US indices relative to their global peers over many years, despite their sell-off in 2022. The technological advances these have brought to the market have meant that the rest of the global marketplace has had to adapt, or face being left behind.

Today almost every company much have a digital strategy (or apparently an AI one, too) and the amount revenues spent on innovation and R&D has steadily grown.

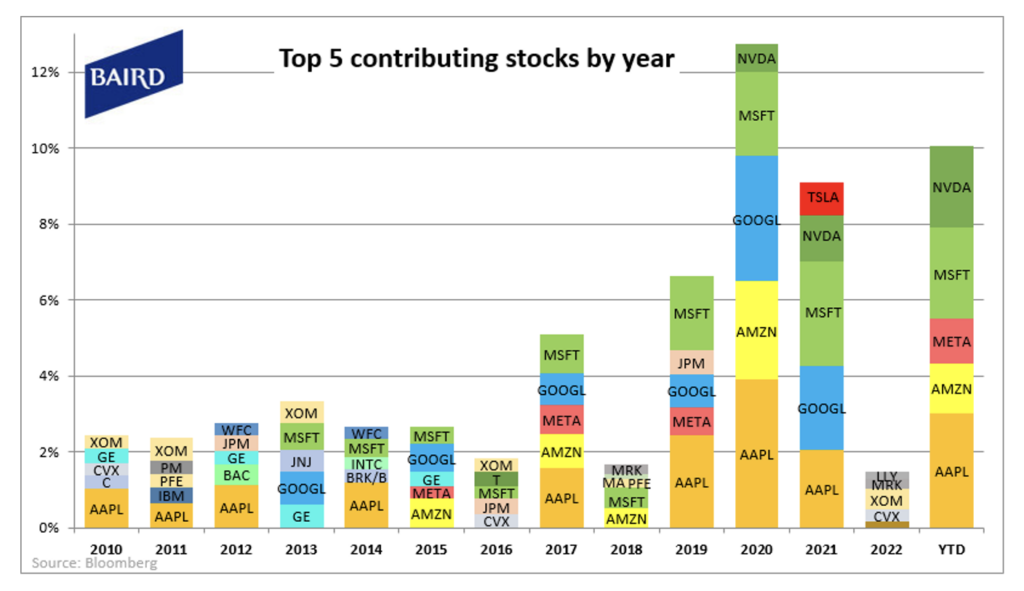

Time has shown there are tech winners and losers, but with their deep pockets, mega-cap technology stocks have succeeded in fending off much of the competition, as shown by the communality of names appearing in the chart for the S&P 500 below:

A biproduct of the rise of mega-cap technology stocks has been a blurring of the lines between what defines a value, growth, or a quality company. Over the past ten years growth and quality have been often seen as synonymous.

While there are many companies that appear to have both growth and quality characteristics, many do not, and a value company can also display quality characteristics.

Another characteristic of the last fifteen years has been a period of unprecedentedly low interest rates as global central banks embarked on an experiment of quantitative easing.

This extraordinary move would normally have led to inflation; however, this has only manifested itself over the past couple of years. This has meant that companies and individuals have grown reliant on central bank and government intervention for survival, inflating valuations far away from reality, eroding the Darwinian nature of markets.

As quantitative tightening kicks in and interest rates normalise, those companies that only survived by over-leveraging balance sheets with cheap debt, or governmental bailouts, may well be exposed; as the Warren Buffett adage goes ‘it is only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked’.

One significant change that no one foresaw was the shift to flexible working, enforced by the pandemic. Historically, the industry was driven by a culture of presenteeism.

Although there is a drive to get investors back into the office, the proof that investment management can be done effectively from a remote location has led to improved mental welfare and a better work/life balance. Of course, human beings are sociable in nature, and working remotely is likely to remain as an option but not the norm, but it is unlikely the industry will return to the 24/7 nature it once had.

There have been many changes since 2008 but what has not changed is the importance of independence of thought, with the ability to hold true to one’s philosophy and process.

While market consolidation has led to product homogenisation with greater focus on profitability than investor outcomes, the best active managers frequently continue to be those free to invest with conviction tempered by accountability.