Normally, the end-of-year review is one of the easier writing assignments: a cursory overview of the preceding 11 and a half months’ events, with the near certainty nothing is going to upset the apple cart between now and 1 January. Given how 2022 has panned out, however, that assumption is fraught with risk – a classic case of yesterday’s news being tomorrow’s chip paper.

So, hesitantly taking those first 11 and a half months as a proxy for the full year, it has clearly been a bruising one for investors, with UK All Companies down 7.8%, Global down 10.1%, and Sterling Corporate Bond losing 14.9% – that last clearly a result of fixed income being hit by rising rates. That said, the area of the bond market affected worst was one, intuitively, you might have expected to be relatively insulated.

Weakest link

The year started with fears of inflation counterposed to hopes of a post-Covid bounce. The latter, of course, never came to pass. Nevertheless, many initial diagnoses of rising inflation ascribed it to the release of pent-up demand as lockdowns eased. Yet that really didn’t nail it – what we have seen are supply-side restrictions that are far from resolved. Indeed, at the time of writing, China was jack-knifing from zero-Covid to opening up with zero preparation, with many anticipating a huge rise in cases in a population with low vaccination rates.

However one explains it, inflation has thrown financial markets into a spin – not least for those assets that are supposed to act as inflationary hedges. Given the name, you would think index-linked gilts – or ‘linkers’ – were a good hedge when inflation is running in double digits. This would be a mistake, as the IA UK Index Linked Gilts sector is the worst performing over the year to the end of November, losing 31.7%. That is more than five percentage points more than the next sector, Technology and Telecoms.

Linker prices are affected by two rates: inflation and the Bank of England bank rate. If the latter is expected to rise, then the price of the linker, like any other bond, will fall. The larger the duration, the greater that effect. So longer-dated bonds will be more adversely affected than shorter-dated ones in a rising-rate environment.

As of 15 December, base rates now stand at 3%, up from their low of 0.1%. The expectations are that rates will peak at between 4% and 5% next year but, as rate-watchers will be keenly aware, that has been a very fluid range over the course of this year.

This has a particularly egregious effect on UK linkers, as they have a much longer average duration than, for example, the far bigger US inflation-linked market: the UK linker sector has an effective duration of 17.9, while its Global Inflation Linked Bond counterpart has an average of 7.5 and is down 10.6% in comparison.

Waning fund flows

Investors have been in a decidedly risk-on mode for the year. September was a case in point: we saw record outflows of £27.9bn, most of which came out of equity funds (£13.6bn – a further record) as pension funds sought liquidity in the wake of ‘that’ mini-budget. Equity redemptions in October were at about half that level, at £6.8bn, though still large in historic terms.

Consequently, October’s Money Market GBP inflows were the largest on record – £66.6bn – reflecting that ongoing dash for cash, as liability-driven investment (LDI) pension schemes were forced to build up extra collateral for their LDI hedges as their funding ratios increased along with yields. Outflows from risk assets that month almost equalled the negative flows for September, at £25.4bn.

Over the year to date, UK investors have pulled £36.4bn from mutual funds and ETFs. Deducting the nearly £20bn of inflows into money market funds gives £56.4bn pulled from long-term assets. The only exceptions to this exodus are mixed-assets funds, which netted £602m.

Given all this, it is perhaps a little surprising to see the FTSE 100 is not far off where it started the year, albeit with some crazy swings along the way – October, unsurprisingly, being the low.

Reports of ESG’s death much exaggerated

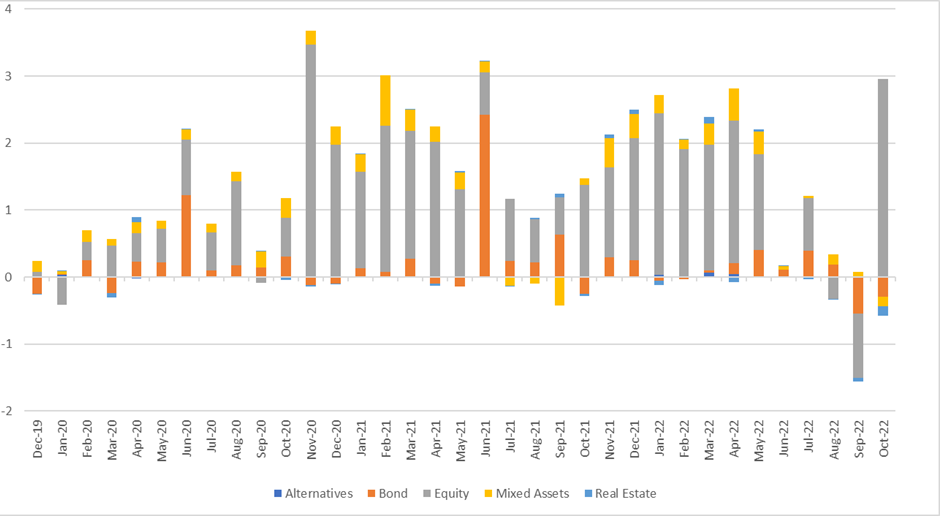

Penultimately, a word on ESG. In general, performance has lagged – though this has depended on the sector, and the strategies and styles dominating therein. Despite this, ESG assets are in the black year-to-date, with ESG equity funds still taking £18.5bn, though they go into redemption in Q3. That said, there does seem to be a rebound already in process, as the following chart shows.

UK ESG Fund Flows, 36 Months, £bn

Source: Refinitiv Lipper

The promise of an ‘ESG premium’, irrespective of market conditions, was always fanciful as I have previously argued, especially with oil and gas making the running (IA Commodities and Natural Resources was the top sector over the first 11 months of the year, up 21%). Certainly, in terms of the sector with the lion’s share of ESG funds (Global), the pronounced growth tilt of ESG funds will have negatively impacted.

If inflation remains elevated next year, this will likely continue to be a retrograde influence on ESG. Indeed, as long as inflation runs to double-digits, equities in general will likely struggle to keep up, let alone bond markets. Indeed, only six of the IA’s 45 sectors are in the black, year to date, of which only two – Natural Resources and Latin America – have beaten inflation.

The good news is that inflation itself may be subsiding – for instance, oil prices have been trending down since June and this should depress production prices while easing the pressure on the consumer. But that is only one piece of the puzzle, no matter how important. Which is why I’m shying away from making any bold calls for 2023. As the pioneer of quantum mechanics, Niels Bohr, said: “Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future.”

Dewi John is head of research UK & Ireland at Refinitiv Lipper