At the time of writing, with a month or so of this febrile year to go, putting a lid on 2021 is asking for trouble. And as for making predictions for next year … well, as economist JK Galbraith said, the only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable.

So here goes.

Defining green

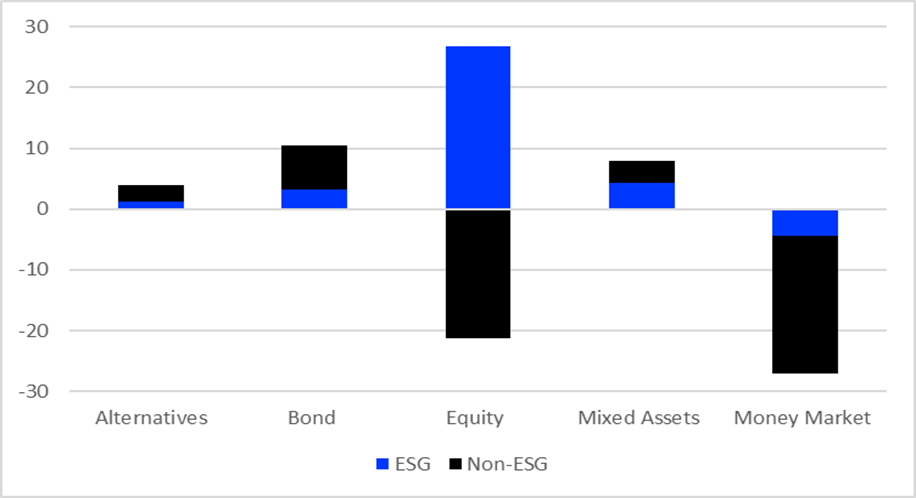

This year has been a bumper one for environmental, social and governance (ESG) funds. A total of £37.3bn flowed into alternatives, bond, equity, and mixed-assets funds in the UK between January and October this year. In particular, as Chart 1 confirms, we have noted a rotation out of non-ESG equity funds into their sustainable peers, with £21.2bn flowing out of the former and £26.8bn into the latter over the first three quarters of the year.

Chart 1: Asset class flows, ESG v ‘conventional’, Q1-3 2021 (£bn)

Source: Refinitiv Lipper

The further you go down the risk curve from equity to bonds, through aggressive mixed assets, and on to cautious, the weaker the attraction of ESG. There would appear to be two drivers for this: first, there are a lot more options for ESG equity investors than bond investors. Refinitiv Lipper records 43 ethical bond funds to 215 for equity, and £28.8bn of that £37.3bn of ethical flows over 10 months have gone to equity vehicles (active primary share classes, UK registered for sale and sterling currency of record).

That cannot be all there is to this, however, or supply would have accelerated to meet the unmet demand in fixed income funds. Some of this lag is to be explained by investors still not being sure what is meant by sustainable fixed income: is it ‘green’, ‘blue’, ‘transition’ and so forth bonds? Or is it regular bonds issued by sustainable companies? Not least, there is the additional consideration that, while engagement is a major element of ESG equity strategy, this is a more problematic approach in other asset classes.

It is a fairly safe bet this trend to ESG will continue over the coming year, with regulation playing an ever-greater role in shaping the market. In October, for example, the UK government released its ESG roadmap, requiring asset managers and owners disclose how they factor in sustainability when making investment decisions.

As with the EU’s (Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation) SFDR, investment products will need to substantiate any ESG claims in a way that is easily intelligible for consumers. While criticisms have been levelled at SFDR – many with good reason – the net effect has been to make greenwashing more difficult, and that has to be a positive.

I would also expect the ESG conversation to progress from ‘should we be doing it’ to ‘is it doing what we need it to?’ As to why – record flows into ESG funds have gone hand-in-hand with record high atmospheric greenhouse gasses and oil production that is second highest, year to date, only to 2019.

So, do investors and asset managers see ESG as mitigating the risk of exposure to oil and gas, or to help realise the targets of the Paris Agreement and Glasgow’s COP26? You can do the former by overweighting tech and cutting fossil fuels from your portfolio; the latter is a tougher call, however, and may need large investors to rethink their exposure to illiquid areas of the market.

The inflation conundrum

The other major trend likely to inform both this and next year is inflation. While I have been dovish on it since the crisis, as I have not seen any persistent drivers, that view has clearly evolved over the past year. I am not, however, making any strong call on this, for the following reasons.

On the one hand, as analysis from Fathom Consulting shows, households have built up huge savings during the pandemic, which – if unleashed – would push up aggregate demand and create further inflationary pressure. Even if those savings remain unspent, there are still clear upside risks.

There are both demand and supply-side drivers to current inflation – for example, on the supply side, alongside the well-documented dearth of lorry drivers, shipping costs have soared as bottlenecks in supply chains have put a strain on the shipping and logistics industry. That said, as the Chart 2 shows, the Baltic Dry Index peaked in early October, and has since declined sharply, indicating the worst may – emphasis on the ‘may’ – be behind us.

Chart 2: Baltic Dry Index

Source: Refinitiv

Which brings me to demand: while it may have been a good time to be in the market for lorry-driving jobs over the past few months, that is not the general situation. UK private-sector employers expect to raise wages by an average of 2.5% over the next 12 months – well below the likely rate of inflation, according to a survey from the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. Much of the public sector will struggle to get that and that will manifest itself in a reduction in real demand.

Overall, Fathom, in a further study, concludes “labour market mismatches should gradually dissipate”, but goes on to caution: “If labour market mismatches were to lead to stickier inflation and were met with a material tightening of US monetary policy, equity markets could be vulnerable given their elevated valuations. There would also be a significant risk of a re-run of the 2013 ‘Taper Tantrum’ in emerging markets.”

US monetary policy has a specific impact on hard currency emerging market debt, but otherwise the same logic applies to UK inflation and rates. Whatever side one opts for in this debate, it is certain that inflationary risks have increased, and investors need to take this into consideration.

Winners and losers

Sectors vulnerable to higher inflation include high growth ones such as technology. Many of these companies will have also borrowed to fuel growth and higher rates mean higher refinancing costs. Those companies with anaemic cashflows, are heavily leveraged – or both – would face strong headwinds felt by both equity and bond holders. Consumer staples may also see their already thin margins eaten up by increasing input costs. On the other hand, sectors that can pass costs onto customers such as financials and energy should benefit from higher inflation.

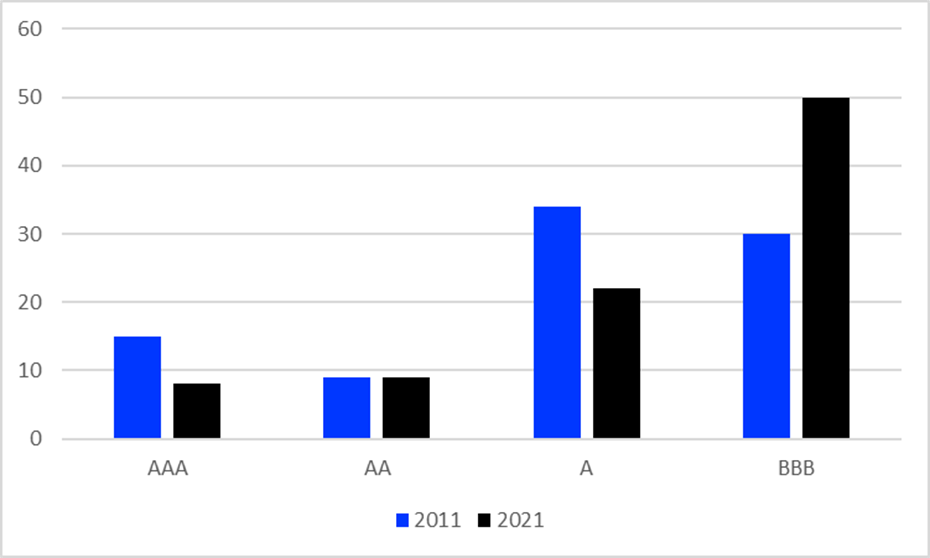

And, of course, inflation is typically bad for bond investors. This in a situation where corporate debt has grown hugely since the global financial crisis, while yields are under pressure. As a result, while the IA Sterling Corporate Bond sector’s investment grade exposure has held steady over the past decade (88% in 2011, 89% in 2021), there have been significant shifts within the investment-grade portion of funds – as Chart 3 illustrates. AAA-exposure has almost halved (15% to 8%), with BBB – the lowest investment-grade rating – rising from 30% to 50%, as fund managers have responded to the lower-yield environment by moving up the risk curve. That could exacerbate the negative effects of rising rates on bonds.

Chart 3: IA Sterling Corporate Bond Investment Grade Exposure, 2011 and 2021

Source: Refinitiv Lipper

Inflation may prove to be transitory, but it would be a bold investor who shrugged off the risk. What is a lot more certain is the role sustainability will have on determining the shape of the investment landscape over the coming year.

Dewi John is head of research UK & Ireland at Refinitiv Lipper