When Shakespeare wrote, “When sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalions,” he may or may not have had in mind the current state of Chinese capital markets. The situation has changed greatly over the past year. Chinese small and mid-sized companies were the best-performing asset class of 2020, returning 72.6%, with Chinese equity funds coming in sixth with a 37.5% return, according to Lipper data (see p13). This year, however, the story has been rather different.

The current sorrow has centred on real estate – and particularly around the country’s largest real estate company, Evergrande. The Hong Kong-listed stock has slumped more than 80% so far this year, and contagion from a potential default or restructuring of its debt – about $300bn (£220bn) outstanding – weighs heavily on both Chinese property and Asian high-yield markets, in which Chinese real estate companies are major issuers.

What the upshot of this will be is not clear. Beijing has not rushed to bail Evergrande out, and local government actions in Shaoxing to cool the housing market have catalysed a liquidity crisis for Chinese property developer Sunac. The company has sought government support. Whether this calms the waters, or is a temporary respite before the flood, remains to be seen.

Then there is the blight that has settled on the country’s equity markets – particularly technology stocks. The government’s tightening chokehold on private companies began to gather momentum when it derailed the IPO for Jack Ma’s Ant Group back in November last year. Then, this April, e-commerce giant Alibaba was hit with a $2.8bn fine following an anti-monopoly investigation. Although the stock rallied by 6.5% the day after the fine was announced, it is down more than 36% over the year.

Not for profit

Chinese authorities have also hobbled the country’s private tutoring sector, valued at more than $100bn, forcing tuition companies to register as non-profit organisations, stating: “Curriculum subject-tutoring institutions are not allowed to go public for financing; listed companies should not invest in the institutions, and foreign capital is barred from such institutions.” Which, needless to say, was a huge disappointment to foreign investors, who had been salivating at the huge addressable market, only partly cracked open.

Government has also restricted online services, from food delivery apps to music-streaming platforms, not to mention the limitation on minors’ gaming times. This follows – at least in spirit – the lead of New York City, which in 1942 banned pinball machines, labelling them “insidious nickel stealers.”

In July, Hong Kong-listed shares in Tencent took a pounding after Chinese regulators ordered the tech giant to end exclusive music licensing deals with record labels globally, limiting its dominance of music streaming in China. The stock is down about 19% so far this year.

Lastly, regulators have demanded that delivery workers be paid at least the minimum wage, along with ruling in favour of other employment rights, thus hitting the bottom lines of the Chinese equivalents of Deliveroo and Just Eat.

‘Enrich yourselves’

This has come as something of a shock to China watchers. The country has become increasingly market-oriented since the late 1970s, as Deng Xiaoping declared “enrich yourselves” and adopted market reforms. These have deepened over the years, with current president, Xi Jinping, extending them considerably. In late 2013, the Chinese Communist Party’s third plenary meeting declared the market was to play a more decisive role in distributing resources, and signalled that government would be less eager to prop up ailing state-owned enterprises.

Yet here we are.

Is this a flash in the pan? By way of example, Chinese leaders have a reputation of carrying out anti-corruption drives when they take the helm – it makes for good PR, and keeps opponents in line. Xi, true to form, did it … and then kept doing it, much to widescale surprise and not a little chagrin (to say the least) from those on the receiving end. Could we be seeing the same now? Is this a slap across the wrists for Jack Ma and co, or something more strategic? It is still not clear how this fits in with China’s opening up of markets over recent years.

Buy on the dips?

In the thick of this, Blackrock is planning to launch a China tech-focused ETF, the iShares MSCI China Multisector Tech ETF, which feels brave in this environment. Or maybe not, as the similar KraneShares CSI China Internet ETF has attracted £3.7bn year to date despite seeing an almost 35% loss.

The Investment Association China/Greater China sector is down 10.6% over the year to the end of August, with the range of returns going from -17.7% to 4.6%. Despite the turmoil, five of the 34 funds have managed to make gains.

It is difficult discerning a neat driver for outperforming and underperforming funds – for example, Hong Kong’s Hang Seng index has been the worst performer, compared with Taiwan and Shanghai (down about 13% over six months, with the other two up about 7%). Yet, at the end of February the best performing fund year to date – Matthews Asia Funds-China Dividend – had 21% of its portfolio in Hong Kong, while the worst performer had 12%. Both had Tencent as their top holding – both with just shy of 10% of their portfolio in the stock. Tencent has underperformed the Hang Seng by about seven percentage points year to date, so that is certainly a strong headwind with which to deal.

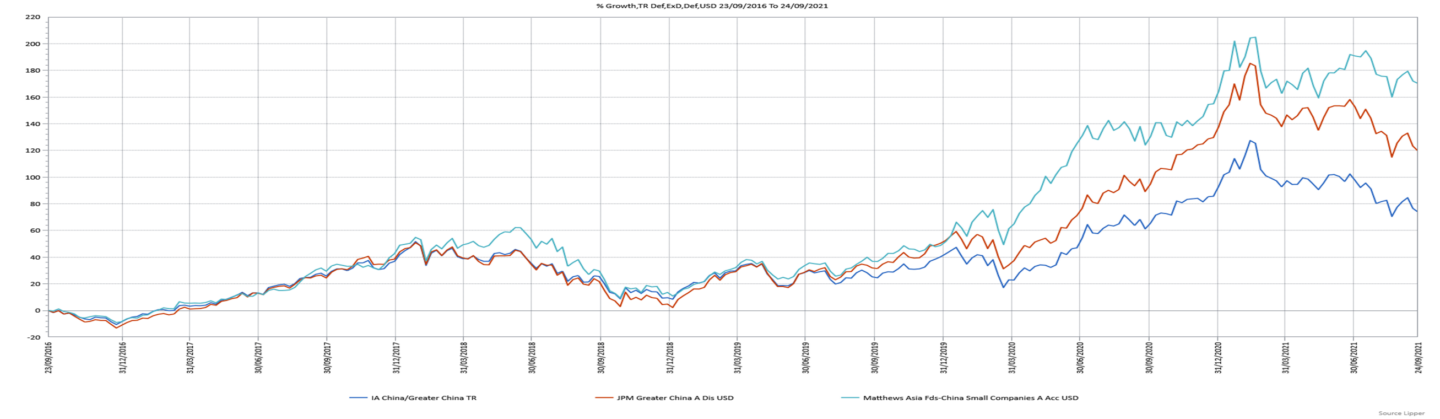

The following chart shows the two funds with the highest five-year returns – as well as among the top over three year and in positive territory over one (both 12.3% compared with a mean of -0.2%) – which are Matthews Asia Funds-China Small Companies and JPM Greater China, which has a five-year Lipper Leader score of 5 (the highest quintile). Given the former is a small-cap fund, the portfolios are very different: back in February, Taiwan Semiconductor, Alibaba, and Tencent made up more than a quarter of the JPM portfolio, with the Matthews fund being, as you would expect, composed of smaller companies.

Hard to like, harder to ignore

China may be a hard market to like at the moment but it is even harder to ignore. It has the second largest equity and bond markets, after the US. Global bond and equity indices have been expanding their China weightings over recent years to reflect the country’s importance.

I have been keen on the Chinese investment story for a long time. Given everything that is going on, however what happens next is anyone’s guess. In launching its Chinese tech ETF, Blackrock may have timed things well, but it is certainly a bold call. As to whether fortune favours the brave in this instance, in the words of ill-fated Chinese premier Chou Enlai when asked about the impact of the French revolution: “It’s too early to say.”

Dewi John is head of research UK & Ireland at Refinitiv Lipper