As someone who has spent two decades at the forefront of the impact investment industry, Ninety One Global Environment co-manager Deirdre Cooper is bowled over by the speed of change on the decarbonisation front.

In the past year alone, the EU has launched a Green Deal, the US has re-joined the global fight against climate change under president Joe Biden and China, the world’s biggest emitter of CO2 emissions, has committed to being net zero by 2060.

“There’s been more progress in the last 18 months than probably in the previous 18 years of my career.”

Cooper (pictured) would know. When the Irish-native began her career as an investment banker at Morgan Stanley in 1997, the concept of sustainable investing was ill-defined. “I enjoyed the challenge of finance but also really wanted to do something that was in an area I felt had more potential positive benefits,” she recalls.

So, she left the bank in 2002 to work for Kashf, a non-profit organisation in Lahore, Pakistan, focused on providing small loans to women from low-income households. She went on to pilot a microfinance award programme, promoting female entrepreneurs, at the United Nations while studying for her MBA at Harvard Business School.

Eventually she was drawn back to Morgan Stanley in 2005 to help with its sustainable finance initiative that was being spearheaded by former principal private secretary to Tony Blair, Jeremy Heywood. A few years later she joined Ecofin, a boutique specialising in sustainable investment, where she looked after a number of strategies, including a decarbonisation mandate for the Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund.

‘There is still so much impact left to be had through engaging with companies’

When the business was sold to a US energy investor in 2018, she landed at Ninety One, then still part of Investec. Over the previous five years she had got to know Graeme Baker, her co-manager on the Global Environment Fund, bumping into him at company meetings and other industry events.

“I knew Graeme and I had a very similar investment philosophy and that we could work together well,” she explains. “We were looking for the same things that make a great company – those that have positive structural growth from decarbonisation but also had strong competitive advantages and could generate good returns above their cost of capital.”

While the recent “long overdue” progress is welcome, there is still a long way to go to meet the Paris Agreement’s target of limiting global warming to 2°C compared with pre-industrial levels, she stresses.

Earlier this year the UN revealed the pledges that have been submitted by signatories to curb greenhouse gases so far this year would only reduce global emissions by 1% by 2030, a far cry from the 45% reduction scientists have said is necessary.

“The decarbonisation journey is literally just starting,” says Cooper. “There is still so much impact left to be had through engaging with companies to encourage them to move more quickly, hoping that they will engage with their governments and regulators.”

See also: Budget 2021: How Rishi Sunak plans on delivering a ‘green industrial revolution’

Taking into account not just financial shareholders but all stakeholders

Cooper says it is hard to tell why interest in impact strategies has only just taken off as opposed to two or three, or even 10 years ago. “It’s not as if the climate crisis has suddenly become significantly worse. It’s been bad for quite a long time and it’s not as if we didn’t have social issues before.”

The fact that sustainable, ESG and impact strategies have generated strong returns throughout the pandemic has certainly helped.

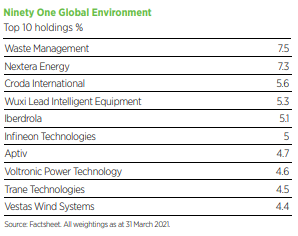

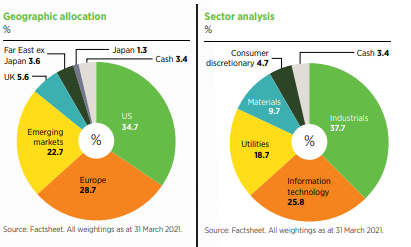

Cooper’s own Ninety One Global Environment Fund was up 47.8% last year, compared with the IA Global’s 15.3%. The fund has expanded rapidly since launch in December 2019, now towering at over £1.1bn. The Sicav version, launched in February 2019, has around $821.7m (£589.1m).

Positive regulatory momentum, extreme weather events caused by climate change and heightened consumer awareness of environmental issues via social media and activism have also steered the conversation and forced the industry to sit up and take note, she adds.

“Our point of view is that we are moving relatively quickly to a world that is really taking into account, not just financial shareholders but all stakeholders,” she says.

“What we’ve started to understand is that financial capital is important, natural capital is important, human capital is important. Companies that do a really good job in thinking about all those stakeholders will arguably have more robust businesses.”

Facilitating the move to a 2°C world

It might seem that the investment universe would be quite niche, focused on electric vehicle (EV) companies and solar and wind plants, but Cooper says there is a vast array of companies to choose from.

“It’s everything from lasers that go into factory automation, which make those machines much more efficient, to the renewable energy companies to the subcomponents that go into EVs,” she says.

One of her top holdings, Infineon, makes the semiconductors that go into wind turbines, solar inverters and energy-efficient dishwashers and washing machines. Its chips are also found in 15 out of 20 of the top-selling EVs.

Step one for Cooper and co-manager Baker is to screen global equities to find areas that are exposed to decarbonisation.

“Think of these as the things that need to happen in order to move to a 2°C world,” Cooper says. “Initially we think about cars, but we should also think about decarbonising homes and buildings, factories and the food chain.”

There is also a conversation to be had around leveraging the hydrogen economy to produce “green steel” in order to address other industrial processes in the carbon-intensive airline, shipping and transportation sectors.

Next, the pair identifies companies that have ‘carbon avoided’ relative to the alternative. To calculate this Cooper and Baker worked with an external consultant analysing direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions sector by sector, trolling through databases and academic research.

“For the power sector we have a database from the S&P that has 30,000 plants around the world,” she says. “We can map those to the people that own them, and then compare them to the World Bank data for the region in which they sit.”

Raising the bar

The bar for impact reporting is much higher compared with your typical global equities manager with a sustainability mandate.

Ninety One Global Environment’s own impact report breaks down carbon risk into three buckets for each company it holds.

Scope 1 represents direct emissions from company-owned facilities and vehicles, Scope 2 the indirect emissions from purchased electricity. Scope 3 measures indirect emissions across 15 categories relating to the company’s supply chain and products once they are sold and used, from business travel to waste generated by activities and end-of-life treatment of sold products.

Cooper says companies are beginning to think about their impact in more granular ways. The proportion of the fund’s holdings reporting ‘carbon avoided’ to a standard the team was happy with had more than doubled to two-thirds by the end of 2019, as did the number of companies reporting on Scope 3 indirect emissions.

See also: Fund buyers wary as number of funds repurposed as ESG continues to rise

The level of reporting intensity is one reason Cooper and Baker insist on having a concentrated portfolio of 25 holdings. The duo checks in with the management teams of their portfolio companies many times a year, in addition to writing, setting and reporting on engagement goals for each individual stock. “That would be really hard to do if we had 60 holdings.”

The fund also has a strict value discipline. The team uses a capital asset pricing model (CAPM) and will typically cut or exit positions that have reached their price target. Turnover was more than 50% last year, which Cooper admits is “very high” for a portfolio with a five-to 10-year investment horizon.

COP 26

While all portfolio holdings are focused on decarbonisation, the companies are at different stages of maturity and have varying degrees of sensitivity to the economic cycle.

Cooper’s second-largest holding, Nextera, is the biggest generator of solar and wind in the US and is non-GDP cyclical and commands a market cap of $150bn. By contrast, Wuxi Lead Intelligent, the fund’s fourth-largest position, is highly cyclical. The China A-shares firm manufactures the equipment used to make batteries for EVs, counting CATL and Volkswagen among its biggest customers.

While the company is still young, Cooper believes “it’s entering a really long, structural growth period because of the Volkswagens, the General Motors, the Toyotas that are committed to transitioning fully to EVs over the next 10 years”.

Other top holdings, like UK-based Croda, which makes bio-based chemicals for household and personal care products, and Danish firm Novozymes, which produces enzymes that go into washing powder, are driven by eco-friendly consumer trends.

With the UK gearing up to host the COP 26 in Glasgow this November, Cooper finds herself “cautiously optimistic”.

“Europe, the US and China are more aligned than ever before when it comes to the climate agenda. There’s true potential for the event to deliver meaningful progress when it comes to decarbonisation.

“Looking ahead to the agenda, we would expect and urge for the focus to be very much on emerging markets, where the transition is more difficult.

“In order to achieve global ambitions for decarbonisation, it’s crucial we bring every part of the world along and ensure a just and inclusive energy transition.”

See also: Asset managers urged to use COP 26 as catalyst for achieving carbon neutral status