The House of Representatives passed a bill to raise the debt ceiling last night (31 May) just days before the US could have defaulted.

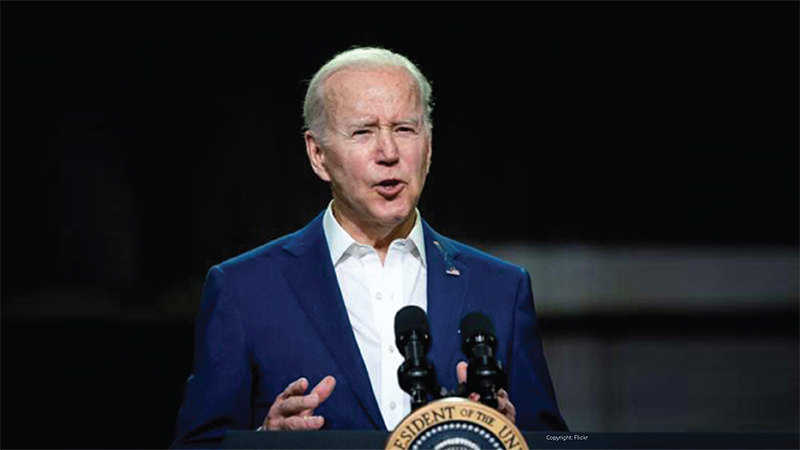

President Joe Biden (pictured) urged the Senate to pass the legislation quickly, with treasury secretary Janet Yellen warning the federal government could be unable to pay its bills from 5 June unless the bill is enshrined into law.

The legislation raises the borrowing limit until January 2025 and features a range of spending cut promises secured by the Republican party during negotiations.

Relief Rally

The agreement has prompted a market relief rally as fears of a catastrophic default have waned.

AJ Bell investment director Russ Mould said: “The FTSE 100 started the day on the front foot as the US debt ceiling deal was approved by the House of Representatives, virtually guaranteeing it will be signed off ahead of the extended 5 June deadline.

“This positive driver for stocks may not last as a US Treasury which has been draining its account at the Federal Reserve to keep the government going, thereby injecting significant liquidity into the system, reverses this policy and starts tapping the debt markets to bolster its coffers.

“For now, though, relief that a US default has been averted is dominating market sentiment.”

While the bill has provided short-term reassurance, the likely longer term impact of raising the debt ceiling is open to debate.

Huw Davies, absolute return fixed income investment manager at Jupiter Asset Management, said the deal will undoubtedly create a further relief rally for risk markets due to the removal of a significant tail risk.

He said: “There is no denying that this round of debt ceiling negotiations has been the most fraught since 2011. However, the realisation that a delay in a deal would have potentially catastrophic and unpredictable consequences for US and global equity markets appears to have brought the two sides to the table.

“However, we now move from a period where the Treasury have been drawing down their general account (by the order of $360bn (£288.8bn) in the first 5 months of this year) to now needing to build its balances back up.

“To what extent they build this back up is open to debate, but they will want to run a significantly higher margin than has been the case recently and may well want to take it back to the $600–650bn (£481.4-£521.5bn) that it averaged in early 2022,” he added.

“This will likely be through a significant rise in US T-bill issuance and the debate will be around how quickly they want to restore the previous healthy margins for the general account, especially when there is an ongoing withdrawal of liquidity also from quantitative tightening.”

Davies suggested the reduction in spending agreed in negotiations is estimated to lead to a 0.1%-0.2% drop in GDP over the next two years.

He added: “However, the probability is that the resolution of negotiations has moved the Treasury account from being a significant stimulant to the US economy to a significant drain. Combined with the marginal, though still negative effects of the spending cuts, the US economy, which was surprisingly robust the first half of this year, looks set to soften into the second half.”