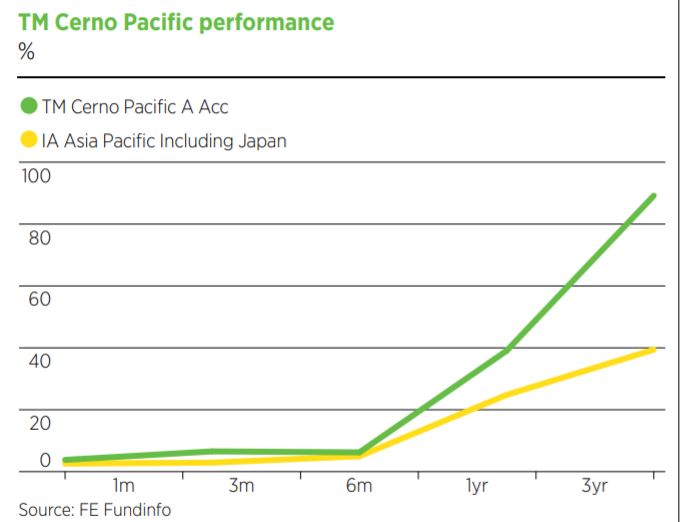

TM Cerno Pacific has been the best-performing fund in its sector over one and three years, notching up returns of 39% and 89.2%, respectively, compared with the Investment Association Asia including Japan sector average of 24.8% and 39.4%.

Managers Fay Ren and Michael Flitton say the secret to their success isn’t complicated: it’s simply about investing in an area of the world that remains off the radar, Asia, despite there being a wealth of companies driving global innovation.

But this is starting to change, according to Flitton. “I think there is a pivot in the world, which is the fact that Asia remains under-recognised in its innovation and its ability to drive change,” he says. “Arguably, maybe the west is over-recognised and we’re beginning to see that.

“What we’ve benefited from is the beginnings of that shift gaining recognition,” he adds. “Obviously, we were in the right place at the right time, but longer term, we are just seeing the beginning of this shift.”

Flitton joined Cerno in 2017. His route to the firm involved a stint in the back office at hedge fund GLG after university, before moving to an equity research role at Citigroup, covering metals and mining, and European chemicals.

Ren joined Cerno in 2011 from university and was trained by the firm’s managing partners Nick Hornby and James Spence. She originally worked on three of Cerno’s multi-manager funds but moved to direct equities in 2014 when the TM Cerno Global Leaders strategy was launched.

The investment team at Cerno is quite small, so rather than have sector specialists, the team is structured as a “small pod of generalists”. It is an approach Flitton argues gives analysts more scope to find commonalities in business models, approaches and management teams across sectors.

“That’s a good way of framing and understanding high-quality businesses, but it also means you don’t get too siloed in equities. You understand the dynamics of what’s moving markets in equities because you understand what’s going on in other asset classes.”

The Global Leaders strategy, managed by Spence, was set up in 2014 with the remit of finding quality global businesses using growth at a reasonable price and holding them for the long term. This strategy was the inspiration behind TM Cerno Pacific, switching focus in 2018 from a multi-manager to a direct equity pan-Asia fund.

According to Ren, when the fund had a multi-manager approach the objective was to achieve emerging market equity returns with lower volatility using a range of external managers. This included equity but also hedge funds and even trade finance funds. This approach, however, didn’t let the team fully tap into the key tenet of the firm’s process: finding innovative companies.

“When we were looking at the different equity funds and realising we wanted to access innovation, we couldn’t find an external manager to offer it,” says Ren. “That’s why we decided to take this inhouse and start doing it ourselves.”

Picks and shovels

Cerno Capital’s ethos revolves around accessing innovation by owning the disruptive companies. But rather than being forced to pick winners among the leaders, the team prefers to choose from the companies that supply these leaders.

To illustrate this, Flitton points to China’s electric vehicle space where, for Cerno, it is not about having to choose between Nio or Xpeng but between the semiconductor companies that sell to them, and increasingly this type of company is coming from Asia. “

It’s a picks-and-shovels approach to disruption because it’s very hard to pick the winner, so the better way to do it is to own some of the essential innovative businesses that supply those companies,” he says.

According to Flitton, fund managers investing in Asia have historically accessed the region via the consumer and by owning companies that sell into Asia such as Unilever. “You get a mismatch of companies globally who rely on exporting to Asia to exploit the rising GDP per capita.”

But he notes the data shows research, development and innovation is increasingly coming out of Asia, rather than being sold into it, so it makes sense to own the innovators. “Historically, that was the west but prospectively, that could well be the east.”

Ren says the team defines innovation as broadly as possible. That might include the traditional metrics of patent applications and R&D, but it also includes the method of doing business, the go-to-market strategy or the business model.

The Chinese internet space, in particular, is well established in this sense, having taken elements of existing western business models like Facebook or WhatsApp and developed them. In fact, in some cases, Ren says the likes of Facebook and Google are now trying to emulate what Tencent and Alibaba have done.

“If you compare WhatsApp versus WeChat, while WhatsApp is just a chat app, with WeChat you have your payments, news outlets, advertising and Instagram. You don’t have to leave the app, meaning people spend probably about half their time online on this product.

“Asian businesses have been very good at aggregating different aspects and using existing technologies much more efficiently, thinking about new ways to access different types of consumers.”

In April, 34 Chinese internet companies, including Tencent, ByteDance, Meituan and Alibaba, were told by regulators to fix anti-competitive practices or risk suffering the fate of Alibaba, which was fined $2.8bn (£2.02bn) the same month. Are anti-trust probes a concern?

Ren says first anti-trust is a global issue and not just limited to Chinese internet companies and, second, she is reassured by the fact Chinese authorities tend to identify a problem and deal with it quickly.

The Alibaba antitrust issue ran for four months from start to finish, whereas similar probes into Google and Facebook have been longer in the making.

“It’s a relief for investors because you don’t have this constant overhang and for the market in the long term, the regulators are not trying to put down these companies,” she says.

“These issues are legitimate, so in the long term it could be healthy for the industry, for more prudent spending, price competition and anti-monopoly behaviours.”

According to Ren, the team doesn’t like areas such as online education because education is a more sensitive issue for the Chinese government, compared with an area such as e-commerce regulation.

She notes there is also a lot of scepticism as to what extent education should be profit-seeking, which can contribute to social inequality and in turn instability; and the Chinese government is notorious for wanting to maintain ‘social stability’.

The team likes China Literature, an intellectual property universe for the Mandarin-speaking world. The company started as a group of amateur fantasy writers posting novels on the internet, which people bought through subscriptions. But it now uses that IP (intellectual property) across a range of digital entertainment mediums, including comics, animation, film, TV series, web series and games.

“What’s interesting about this company is that they amassed a huge library of content when film and TV content adapters started noticing the quality of their library, and started licensing their novels to make into TV and film. That has created a whole new revenue stream,” says Ren.

Following the ideas

China accounts for just over half (51%) of the portfolio, with Japan the second-largest geographical weighting at 23%.

Flitton says when one thinks about innovation it is hard to look past Japan, despite the fact it has struggled to compete with China. However, western approaches to Asian funds often exclude Japan, preferring standalone funds to access the country.

He adds that some interesting things are happening in digital in the country, mandated by the Japanese government.

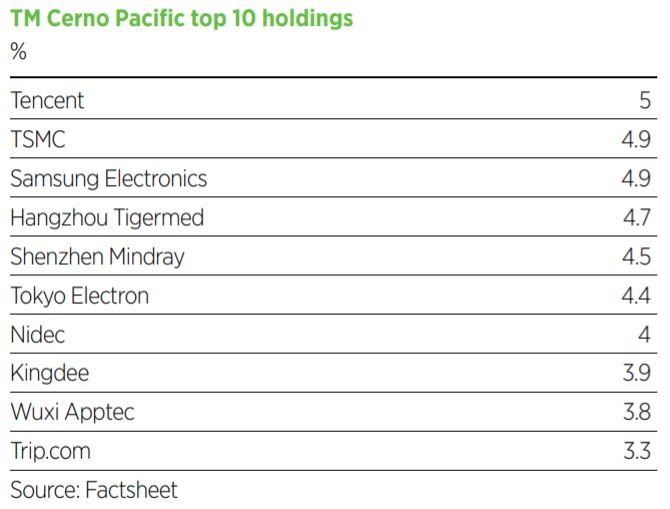

Again, it is about investing in the suppliers that facilitate innovation, says Flitton. TSMC is a leading Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturer, but it uses equipment made by Japanese producers and so the portfolio contains Tokyo Electron and Disco, both high-precision manufacturers of semiconductor equipment with very high market shares.

Japan is also in an interesting position geopolitically, according to Flitton, because it has a degree of trust with both China and the US. “China is now trying to build out its own semiconductor industry, but they will need Japanese equipment to do it,” he says.

“So, our view is when you’re investing in Asia and you’re looking for IP and innovation, you can’t ignore Japan – it’s fundamental to the region and to the world.”

Being bottom-up investors, the geographical split in the portfolio is purely down to where the opportunities lie. In addition to China and Japan, the strategy is divided between Taiwan (10%), Korea (5%), Australia (5%), Latin America (3%) and Singapore (3%).

“Historically, people have viewed emerging markets on a country basis but for us it’s just a question of where the ideas are. Where are the interesting propositions? And once you start thinking about it like that it makes very little sense to think about things in an Asia or Asia ex Japan sense,” Flitton says.

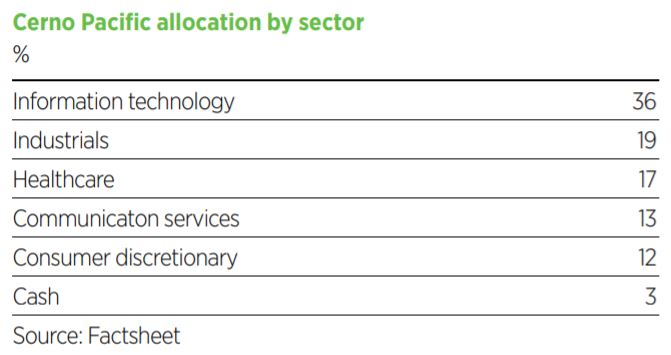

The portfolio fared well last year by its innovation slant and exposure to semiconductors, internet and healthcare. The rotation into value this year has been felt by the fund as cyclical stocks underwent a valuation rerating, but Ren says the underlying fundamentals have not changed.

“We went through the first quarter results and the underlying growth of these companies hasn’t been compromised,” she says. “It’s a pure valuation re-rating for the most part and given we don’t have exposure to sectors like energy, real estate or banking, which were some more beaten-up areas last year.”

Flitton adds there are undervalued stocks out there which are highly levered to economic performance, and they have optically very high growth. “Our view is that those re-opening type stories have a lack of persistence to their earnings, and ability to drive their own persistence to earnings growth.

“The stocks within our portfolio are in control of their own destiny in that sense. They have the ability to grow significantly above market.”

This article is taken from the July/August 2021 issue of Portfolio Adviser. Read more here.