Modern slavery exists in the supply chains of almost every business in the UK, making it nearly impossible for investors to avoid exposure to, according to CCLA.

The UK imports $26.1bn worth of goods a year which have a ‘very high likelihood’ of coming from slave labour, according to the Walk Free Foundation, and while many leading British brands would publicly deny this, the Ethical Trading Initiative found that 77% suspect modern slavery in their supply chains when asked anonymously.

Despite universal condemnation, modern slavery is rampant across every sector of the UK market – and most investors are oblivious to it, according to Dame Sara Thornton, consultant to CCLA’s modern slavery programme and the UK’s former independant anti-slavery commissioner.

“Forced labour isn’t just a bug in the system, it’s a feature of the system. This is so endemic and that’s why it needs to be addressed,” she said.

And the UK’s copious links to modern slavery aren’t purely from overseas cases. There are an estimated 122,000 people in modern slavery in the UK according to the British Safety Council, meaning almost two people in every thousand are victims of slavery. Yet the British government is only aware of 17,000 registered cases of it in the UK.

“Investors aren’t aware of the scale of this and just how ingrained it is – mainly because these things are often hidden from view,” Thornton said. “If any of us knew sometimes just how close we were to the exploitation of another person, we’d be quite horrified.

“So I think a key part of our work among investors is raising awareness. People might be aware of car washes or nail bars, but generally people have no idea. That’s because it’s criminal and it’s hidden. It’s unobservable.”

Weak legislation has turned the UK into ‘a dumping ground‘

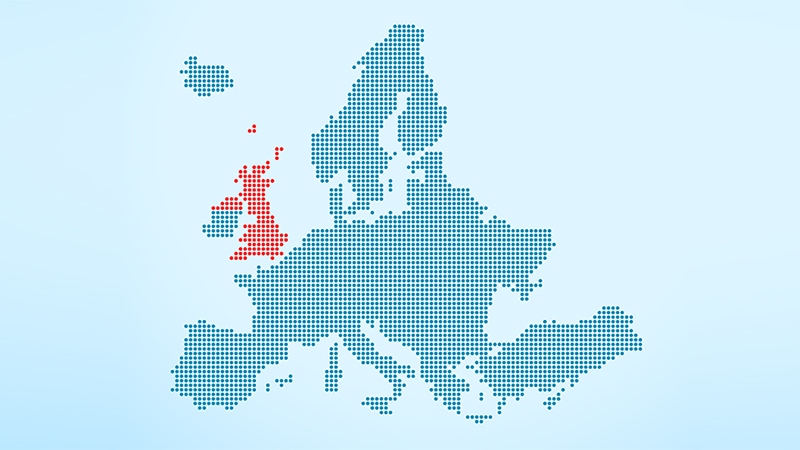

Yet despite its ubiquity, the UK has done little to prevent modern slavery compared to its peers in Europe and the US, putting British investors and consumers alike at higher risk.

The European Union made it mandatory for all companies above a certain threshold to disclose human rights due diligence under the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, and a forced labour ban means products tainted with forced labour cannot be sold in European markets – a far cry from the floods of slavery-linked goods still entering the UK.

Thornton and her colleague at CCLA Martin Buttle have urged the House of Lords and Cabinet Office to get UK legislation up to scratch with its peers. Not doing so could see the situation deteriorate further as illegal goods and services gravitate towards the UK and its weaker laws.

Buttle said: “We don’t currently have a UK forced labour ban or mandatory due diligence legislation. It is time now that we have similar legislation to our closest trading partners, because the risk is that without it, we become a dumping ground for these products.

“Even the US has the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act now, which it’s using to great effect to stop products tainted with forced labour coming into the US.”

The need for improvement in the UK’s Modern Slavery Act has been widely agreed upon since its introduced in 2016, but change has been slow to achieve. The result is a piece of legislation that is not fit for purpose and appears archaic beside its neighbours’ more robust laws.

Thornton said: “The previous government accepted the need for the Modern Slavery Act to be toughened up and tightened up, and had announced they were going to do that – they just never passed the legislation. Even Theresa May said she thinks her own legislation should be toughened up and tightened up.

“In terms of this current government, I have not yet seen what they think about due diligence. Quite a few ministers have talked about workers’ rights, but the most important thing is that they address modern slavery in that too. We’re really hopeful that the government will look to see what’s happening in Europe.

“The real risk is if our closest trading partners have much tougher legislation, that the UK becomes a dumping ground. That’s what we’re very concerned about and quite a lot of the companies we have engaged with are also very aware of this risk.”

Businesses need to get to grips with their own supply chain

Identifying modern slavery within supply chains can be a challenge for companies in the first place, especially if they use multiple subcontractors or rely on overseas suppliers.

Yet some large-cap businesses are simply not putting enough effort into understanding where they are sourcing materials from, according to Thornton. This is not only poor governance from an ethical perspective, but not having a grasp on this basic knowledge is poor from a business and security perspective too.

“Companies that are coming up in the lower tier [ratings] – which are big companies – are not doing enough to find and understand the risks in their own supply chains, so we expect them to do more,” Thornton said.

“We want to ensure that they have systems in place so that when they find a problem, they will address it and most importantly, they do something about the poor workers who have had their wages stolen.”

Failing to analyse supply chains is misleading to consumers who assume their products are not illegally sourced, but also puts a company’s shareholders at risk.

“When we as consumers are buying things, it’s really very difficult to trace them back from our purchase to the field or factory. So we utterly rely on companies to do the right thing – particularly when they’ve got long global supply chains,” Thornton added.

“And as investors, we want to understand companies we have equity in because it’s a material risk. It’s a risk to their business because of regulation, it’s a risk to their reputation, and it’s ultimately a risk to their share price.

Companies are aware – but not acting on it

However, identifying modern slavery is the most basic aspect of preventing this growing issue. Many British companies haven’t taken proactive steps to actually stop violations once they’ve found it, according to Buttle.

It may be this lack of action that has led the number of people in slavery globally to increase by 10 billion since the Modern Slavery Act was first introduced in 2016.

“If you look at our benchmark, the fix it element is the lowest scoring area, and many companies are not disclosing fixing it even if they are aware of cases,” Buttle explained. “In an ideal world, there would be some consultation with those people about what remedy they require.

“The remedy will differ depending on circumstances, but we do expect companies to consult with rights holders, with civil society organisations, and with trade unions to understand what the situation is and then putting that remedy in place. They won’t always be able to do that on their own, and they will actually need to work with their peer companies because there might be a supplier that’s supplying to multiple companies.”

Fixing cases of modern slavery in supply chains is not straight forward, and preventing future offenses is even more challenging. But not doing so means the problems will repeat themselves and become greater with time as we have seen, according to Thornton.

It is for this reason that the ultimate responsibility for amending this issue that has blighted the UK relies on the companies financing modern slavery.

“It’s not enough just to investigate an individual case – you need to think about the systems and structures that are allowing this to happen in the first place,” Thronton said. “And the tremendous pressure on commercial companies to source products at the cheapest possible price, linked with vulnerable populations, is the perfect storm for people to end up in forced labour.

“That’s the difficulty, and I would absolutely argue that businesses have got a huge responsibility here. “

Exposure is unavoidable without change

Ultimately, modern slavery is more rife in UK supply chains than in neighbouring nations and the government needs to ensure British businesses are not continuing to idly finance it.

Because currently, even the most ethical investor in the UK would struggle not to find traces of modern slavery within their own portfolio.

“Any investor that has a wide portfolio of companies will have exposure to it,” Buttle said. “And the Modern Slavery Act doesn’t even include value chains or downstream risk, so investors aren’t actually required to engage with companies in their portfolio because that is not a supply chain risk.

“That is one of the policy positions that we think should be mandated in law because anyone with a wide portfolio of equities will be exposed to that risk.”