The world witnessed an extraordinary demonstration on Friday 20 September 2019 involving millions of people across 185 countries protesting government and business inaction against climate change.

The growth in scale and momentum is quite remarkable given that the movement can arguably be dated to a one-schoolgirl protest involving Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg sitting outside the Swedish parliament in August 2018.

She has more company now. Thunberg made an impassioned speech to the UN assembly, full of accusations that nothing had been done about climate change and calling out a betrayal.

“You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words. The eyes of all future generations are upon you. And if you choose to fail us, I say we will never forgive you. We will not let you get away with this. Right here, right now is where we draw the line.”

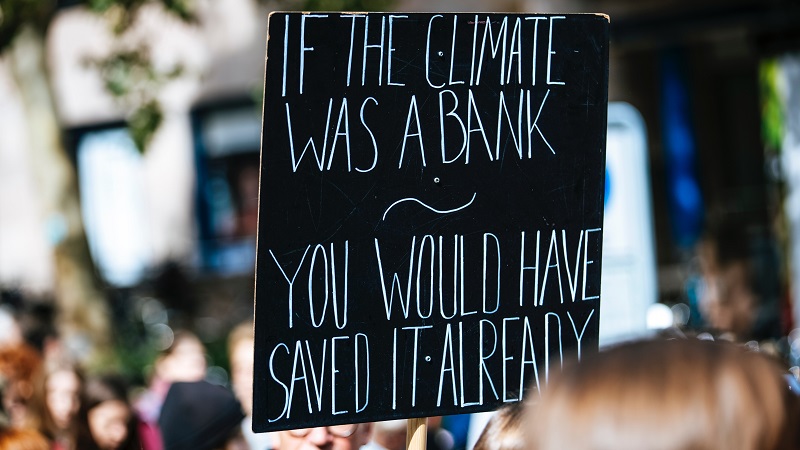

The speech was aimed at politicians, but if the campaign was to turn its fire on the global investment industry would that be justified?

Well, there is certainly a reasonably strong case for the defence.

Investor climate initiatives

A host of fund managers are signed up to the Principles for Responsible Investment. Among other things, it recently called out the climate change denial lobby and suggested that investors need to challenge companies if they are financing such black arts.

Another recent statement from institutional investors managing US $16.2 trillion called on companies to tackle deforestation with the focus on the Amazon in particular. Indeed some of the language used could come from the campaigners themselves.

Indeed, the PRI was also involved in helping coordinate and indeed creating the Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance.

Announced at the same UN conference which Thunberg addressed, it involves pension funds, insurers and asset managers committing to having carbon neutral portfolios by 2050.

Asset managers and insurers

The stand-out name, among many significant firms, is insurance and asset management giant Allianz.

Denmark’s MP Pension, with US$20bn in investments says it is pulling out of the top ten oil companies as they simply cannot meet the Paris targets.

The move is not based on a whim, or what you might call purely a political stance, but is based on investment research, which it intends to apply to the next 1000 oil firms to see if any are making enough progress in terms of their transition.

German mutual finance giant Union Investment is analysing as many as 72,000 securities scoring them in terms of how close they are to meeting the Paris targets as of a series of investment strategies it offers to clients.

Of course, we know that globally most firms are offering impact strategies, pure environmental strategies, and many more applying ESG disciplines across their books.

Almost every day, another source of information emerges from ratings and research firms while the consultancies offering specialist advice are being bought up, arguably demonstrating the value in this information whether it is sold for proprietary use or distributed more widely. We have just seen the launch of a new global carbon credit index from IHS Markit pricing carbon per tonne (incidentally it is currently $23.65.)

There is also a huge amount of capital funding variously wind, solar, EV and AV and crucially batteries while renewables play an increasing part in the energy mix of many countries.

Regulators and central banks

Meanwhile regulators are urging financial institutions to do more.

The climate protestors involved in the separate and feistier Extinction Rebellion protests this summer past targeted the Bank of England, but its Governor Mark Carney has actually proved to be one of the most significant advocates for change.

He is even prepared to make speeches to his fellow central bankers urging them to get their act together.

EU regulators are among those trying to create an agreed taxonomy to help investors understand what they are getting from a fund labelled as sustainable.

Related: How to relax and learn to love sustainable investing

Is ESG enough?

So, if there was a meeting between Greta and her advisers and some brave representatives of the asset management world, there would be at least some common ground.

Yet is it enough?

These are all slightly different types of action. Applying ESG integration may help with the risk management, it certainly does no harm and as most managers would attest doesn’t hurt returns either, but does it represent the fundamental shift campaigners want to see?

The 2050 target is highly significant particularly as the signatories are undertaking to start asking more searching questions about the stocks they hold.

The undertaking is pretty extraordinary from a firm with the heft and influence of Allianz, but it is also a herculean task. At the same time, 2050 is half a lifetime away literally so for some of those in the most climate stressed parts of the world.

We have to expect that some of the signatories, making up the grand totals of assets, will do better than others.

Laggards

Most importantly, no-one has yet totted up assets influenced by the ‘coalition’ of big investors which do not want to get involved.

The Dutch civil service pension ABP has been called out recently by Greenpeace for doubling its investments in Gazprom and trebling those in Rosneft, while its oil and gas holdings generally have increased by around £2.5bn since 2016.

ABP also happens to be one of the world’s largest pension funds yet it is obviously not the only large investor not to read the memo on investing in carbon intensive firms.

We must assume that similar questions will be asked when there are big institutional investments in Aramco, when it lists, possibly in a matter of weeks. Most of the focus is likely to be on the list price and likely returns rather than sustainability concerns.

In fact, that dilemma is very clearly expressed in the recent research from BNY Mellon which discusses investors’ views about climate change and in particular stranded assets

As the report says: “First, current progress on carbon pricing – envisaged under the Paris Agreement – is so slow that investors are left to guess the point at which draconian governmental action will become inevitable in future.

“Second, in that event, investors are also left to figure out what will happen to stranded assets – e.g. coal and oil left in the ground, and coastal real estate exposed to rising sea levels.

“They could suffer significant losses in value ahead of their anticipated economic life. For example, there are 1.1 trillion tonnes of proven coal reserves worldwide, equal to 150 years at current rates of production. The choice is whether to mitigate their investment risks now or later in the future at potentially higher costs.”

Investors hold back from ‘Minsky moment’

No doubt these dilemmas would be given short shrift by campaigners. They will point to rising temperatures, extreme weather putting pressure on the most vulnerable on the planet, and the most recent pessimistic report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change about sea level rises.

Moving forward, we suspect that the crux of the argument will revolve around the targets for warming, and variously companies’ likelihood of meeting these targets through transitioning away from carbon intense practices.

Whether that is 2050, 2040 or even 2030 – the UK’s Labour party conference has just embraced the latter extremely ambitious target is another matter.

For example, while Mark Carney is clearly very concerned about climate change, he has also warned of a Minsky moment if we transition too quickly leading assets prices of many major stocks to plummet and hurting the economy.

We suspect some of the subtleties will be lost with such targets. How carbon intensive should the extraction of rare earths and other metals be when many of these commodities are needed to drive the transition in electric vehicles and power generation and storage?

How do we view engagement that improves company behaviour, maybe meets some of the development goals, but it still remains relatively carbon-intensive?

How much can investors adopting zero-carbon policies bring about the shift or will that require the force of law to keep assets in the ground, or at least to add the full carbon cost to most economic activity?

These are supremely difficult questions to answer.

For now, we think that the campaigners would give the investment management industry short shrift but we would argue that would only be fair depending on which investors and asset managers they were talking to.

One thing we can say with certainly is that given the extraordinary level of investment required – the scale of the refit – the solution has to fully involve the investment industry.