The Financial Conduct Authority is facing the industry “calling time” on investment trusts, according to multiple senior spokespeople, who warn that if cost disclosure regulation isn’t revoked for closed-ended funds the sector could disappear altogether.

This comes following a stark warning from Baroness Bowles who, in the past three months, has called for the removal of cost disclosure twice in the House of Lords – both during the debate on the Financial Services and Markets Bill 2023 and again in a debate on the UK economy. Having also penned a letter to FCA chief executive Nikhil Rathi to no avail, she and a number of her colleagues are in talks with the Treasury in what she has described as an “emergency situation”.

“The FCA is not fulfilling its principal objective, which is for stability in the markets,” she told Portfolio Adviser. “This does not mean stability of a graveyard – and leaving the trust sector to wither and die – but stability of fair and operating markets, accessible markets.

“By not taking action, this is a failure and really very dire. In my view, it fulfils all the criteria for a judicial review – procedural unfairness and irrationality. I think not fulfilling your principal objective is probably both illegal and irrational.”

Cost disclosure regulation: An explainer

Under Packaged Retail Investment and Insurance Products (PRIIPs) regulation, which first came into play in the UK in 2018, all listed investment trusts and closed-ended funds must produce a KID (key investor document), which outlines their ongoing charges figures (OCFs) and potential risks to investors.

It runs parallel to the 2009 Undertakings for the Collective Investment in Transferable Securities (UCITS) regulatory framework – which applies to the European Union and any UK-based open-ended fund marketing itself to EU investors – from which trusts have always been exempt. Open-ended funds are still only required to produce the UCITS Key Investment Information Documents (KIIDs) for information, but are expected to transfer to the new UK KIDs by 31 December 2026.

The UK is currently working on updating its own PRIIPs regime which it believes is better suited to the home market. A consultation into this began in December last year and finished in March 2023. However, the response to this – which was published last month – flagged a number of concerns, particularly the fact that KIDs require both funds and trusts to disclose their OCFs.

While this arguably improves transparency for open-ended funds, there is a problem with their closed-ended counterparts: trusts, despite investing in a collection of securities, are individually listed companies in their own right. They therefore have a share price and an underlying net asset value (NAV), on which their price trades at a discount, or premium to, depending on daily market dealings. Investors therefore buy shares in them and buy them at ‘price’, and yet their published OCFs are applied to their NAV. This was confirmed by the FCA via the introduction of cost disclosure guidance as part of the new PRIIPs regime on 1 July last year.

Richard Parfect, multi-asset portfolio manager at Momentum Global Investment Management, explained: “The share price that investors pay for a trust is what the market has adjusted downwards to in order to account for those internal costs having already been “paid”; resulting in the earnings per share (EPS) and NAV being lower than would otherwise have been without such costs, consequently giving a lower share price.

“Any listed company has costs to cover its operation. However, it is only investment companies that have to report them in this manner; other entities such as Marks & Spencer or GSK do not have to produce a KID and the investors in such companies do not have to report them in turn to their own investors.”

This can make investment trusts look far more expensive than they actually are – not only because it causes a ‘double layering’ effect with reported costs, but because many of them invest in illiquid assets with higher trading costs. According to data from Hawksmoor Investment Management, some 50% of new issuance over the last decade has been in alternative asset classes. But while they invest in ‘expensive’ assets, investors are buying the company’s shares and do not physically bear the brunt of these charges. And yet, the KID documents make it look as though they do.

“This anomaly slipped through the net and into PRIIPs,” Baroness Bowles explained. “What has happened now is that, in tidying up the rulebook, the UK has put a bad bit of PRIIPs into its UCITS regulation all by itself.

“This kind of issue was happening while we were in the EU and there is this notion that the UK is now more nimble [post Brexit]. But now the FCA says it will look at it in about three years’ time – it beggars belief.”

Impact on wealth managers

The additional layer of complication is that many wealth managers, fund-of-fund managers and discretionary fund managers are now unable to hold investment trusts, because their charges will appear far more expensive than they are to financial advisers.

Parfect said: “What the FCA has failed to understand is that, despite the best intentions, IFAs are time-strapped people who are not necessarily well-versed in their underlying investments – because that is not their job.

“Their job is to understand the tax and the financial planning aspects for their clients. They rely heavily on software packages, which have a very clean and easy column showing costs, but they can’t show a value figure.

“It means that, when they have 95% of their attention on the cost side and very little on the value side, they just cannot quantify it. If you mix that in with the fact it is a completely erroneous figure, then we have a complete market failure mapped out.”

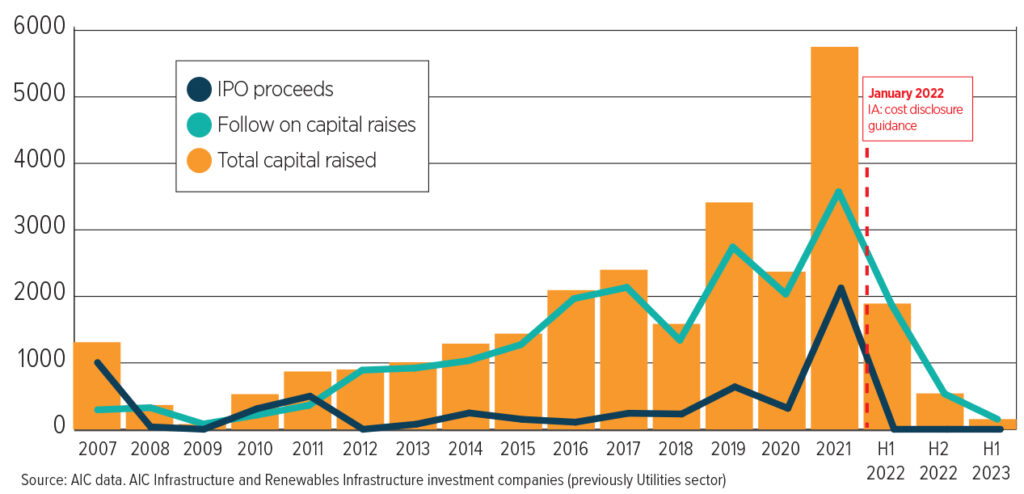

Capital raised by infrastructure and renewables investment companies 2007 to H1 2023

Research from Gravis Capital’s William MacLeod, using AIC data, found that since confirmation of cost disclosure guidance on 1 July 2022, “investment products appeared to rise in price from sub 1% to well in excess of 1%”.

“Investors report anecdotally, and this is endorsed by brokers across the market, that they have been forced sellers of the affected companies much against their will and investment thesis, resulting in an artificial approach to investment management focused on cost rather than investor outcome,” he said.

“It also means that, if you’re running other people’s money, you cannot actually describe to them what it is that they are looking at. Our world is complex enough; what we should be trying to do is to simplify what we give to the end investor.

“We have fundamentally failed to do that – what we are actually doing is making it more and more complex with every move that we make. Because now that cost disclosure for an investment company is effectively double counting, it is being made to look artificially expensive. That is so unhelpful and just wrong.”

Parfect added that the regulator’s lack of action has led to double standards, given their recent roll-out of Consumer Duty means investment managers must “act in good faith towards customers, avoid causing them foreseeable harm, and enable them to pursue their financial objectives”.

“For firms to achieve those objectives, it is not unreasonable to expect the regulator to aspire to conducting its own business in the same spirit when dealing with a situation such as this,” he reasoned.

“Particularly so given the direct impact the guidelines have in eroding the consumer’s understanding of costs, as well as the ability for investors to support products designed to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This means investors cannot pursue their financial objectives because it prevents portfolio diversification.”

Indeed, research from Baroness Bowles has found that cost disclosure regulation fails on 12 of the FCA’s key objectives and principles. These include: ensuring that markets function well and are fit for purpose, reducing risk, transparency of pricing, and the orderly operation of markets.

Widening discounts

Investment trust discounts are indeed becoming wider across the piste as their popularity wanes. According to research from Portfolio Adviser, using data from the AIC, 368 out of 400 (92%) trusts are currently trading on a discount to their net asset value (as at 10 August 2023). Some 235 of these (68.9%) are at more than a 10% discount to NAV, 16 (4.3%) are on more than a 50% discount, and the least popular investment trust – GRIT Investment Trust – is on an eye-watering 88% discount to NAV.

Of these discounted trusts, the average discount of 16.9% has almost doubled relative to their five-year average of 9.8%.

Lucy Walker, founder of AM Insights and chair of the Aurora Investment Trust, said trust discounts are at levels not seen since the 2008 global financial crisis, yet this does not correlate with wider equity markets.

“Anecdotally, the FCA’s requirement for funds to include trust’s fees in their OCFs has had a huge impact,” she reasoned. “Multi-asset funds that owned a chunk of trusts saw their OCFs rocket as a result. In a world where costs are a top consideration, how long will these trusts continued to be owned for?”

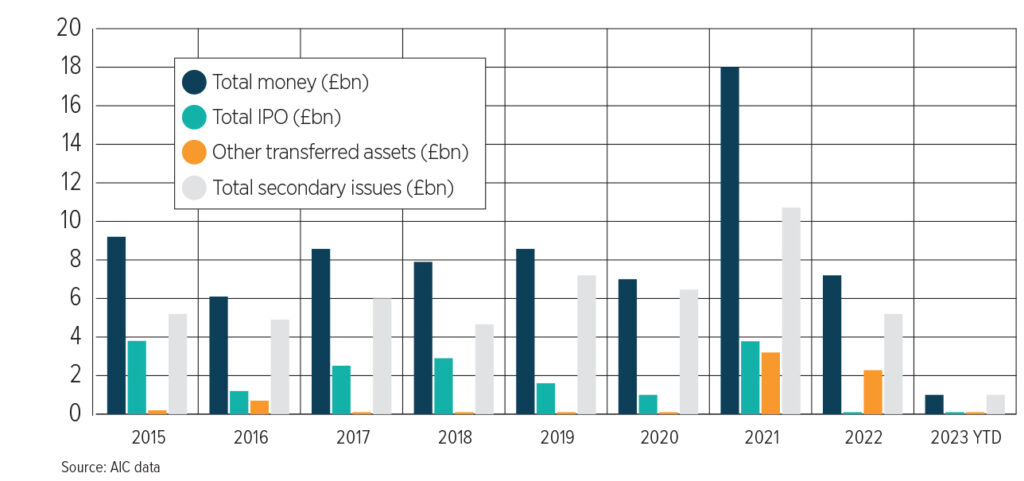

Capital-raising from investment trusts from 2015 to H1 2023

Other factors at play

Of course, trusts’ widening discounts are not solely the result of cost disclosure regulation. According to a recent series of articles from Hawksmoor IM entitled We Need to Talk About Investment Trusts, wealth management consolidation and subsequent requirements for greater scale and liquidity have reduced the number of trusts in their investable universe. The pieces also reference weakening governance from investment trust boards, with a number of investment managers falling out with their board of directors over recent months.

Annabel Brodie-Smith, communications director at the AIC, said: “The cost disclosure regime is having an impact on the popularity of investment trusts, but of course the poor investment environment and higher interest rates are also influences.

“It’s also worth pointing out that the development of centralised investment propositions, including model portfolios, has happened in a world where open-ended funds dominate.

“The structure of the market – from platforms to the model portfolios themselves – has been developed to suit the trading mechanisms and commercial dynamics of open-ended funds.

“These barriers are not insurmountable, as many advisers and wealth managers who use investment companies prove. However, they do make open-ended funds an easy ‘default’ option.”

Kamal Warraich, head of equity fund research at Canaccord Genuity Wealth Management, added: “Discounts are widening for a variety of reasons, including persistent outflows from UK assets, international shorting of UK assets through the FTSE 250 index (trusts are overwhelmingly part of this index), and due to the general risk-off approach since 2022.”

But perhaps the stubbornly wide discounts, the shrinking number of wealth managers and the falling number of investment trusts have created a vicious circle. Several investment trusts in 2023 alone have been merged into other larger trusts, as their discount means they are unable to raise fresh capital through markets.

This, according to Gravis Capital’s MacLeod, means the UK’s investment trusts could end up migrating overseas.

“Overseas-based investors are circling the UK’s investment company sector. They’re not vultures, but the outcome is the same and before long we could see ownership of more UK-based assets move abroad,” he warned.

Industry mistrust

Most commentators believe the requirement to provide OCFs on a trust’s NAV comes from mistrust and poor publicity of the investment industry.

Baroness Bowles pointed out that, around the time when PRIIPs first came into play, ‘closet trackers’ – funds which often mirrored benchmarks but charged investors active management fees – began dominating financial media headlines.

“I think there may be some memories of that episode lurking around,” she said. “It was likely right that something was done about this. But a huge portion of the investment trust market is focused solely on innovation and invests in the likes of wind farms, solar batteries, private equity firms and SMEs [small-to-medium enterprises] – none of which have traditionally been in the business of charging excess fees. And they are now put in the position where they have to declare costs that are inaccurate, to their detriment.”

Momentum’s Parfect concurred, adding: “There is a narrative out there that, somehow, we’re all greedy bankers and we are here to rip everyone off.

“This mistrust of the industry is so disruptive. As investors we can see all the sectors of the UK economy which need capital, and we are keen as mustard to fund them. But we can’t.”

A world without investment trusts

Baroness Bowles believes the regulatory misstep occurred because, despite concerns from investment professionals, “it seemed not to matter more broadly because one could still proceed under UCITS”.

However, investment trusts offer investors a number of benefits that their open-ended counterparts cannot.

Warraich pointed out: “There is board oversite, they can borrow money to potentially increase returns, they can manage their balance sheets to smooth dividend growth and investors can buy them at a discount. And, importantly, they plug the gap on the liquidity mismatch issue, because they are a perpetual capital vehicle – fund flows do not impact the NAV.”

Using AIC data, Brodie-Smith compared the performance of sister open-ended funds and investment trusts, those with the same manager and mandate, over ten years to the end of June 2023. She found that 69% of the investment trusts outperformed their sister open-ended fund over the decade.

“Investors get access to a broader range of assets from wind and solar farms to care homes and private equity,” she explained. “Investment trusts have a fixed pool of capital so fund managers can take a long-term view of their portfolio and, unlike open-ended funds, managers are never forced sellers.”

Investment trusts’ ability to invest in illiquid assets – such as renewable energy infrastructure – also offers vital funding to companies which are aiming to reduce the UK’s carbon footprint and dependence on fossil fuels.

Using AIC data, Portfolio Adviser found that assets across the IT Environmental, IT Renewable Energy Infrastructure, and IT VCT Specialist: Environmental sectors, hold combined assets of £25.7bn. This is not including other innovative trusts sitting within IT Biotechnology & Healthcare, IT Technology & Tech Innovation, and scattered across various other sectors such as infrastructure and property.

And yet, the average renewable energy infrastructure trust is currently trading on a 22.1% discount to NAV (as at 22 August).

Parfect said: “Certain types of infrastructure, such as GP surgeries or UK lab space – let alone all of the renewable infrastructure – are vital if we want to champion the UK as a good place to list and invest in going forward.

“But these businesses cannot raise enough primary capital because their trust’s shares are trading at discounts.

“And, because as multi-asset managers we are hamstrung, we cannot even see these significant discounts and buy into the trusts, which would narrow their discounts and benefit both our investors, and the broader economy.”

Why is the FCA not acting?

Baroness Bowles said she finds it “very difficult to understand” why the FCA is not looking into the cost disclosure issue, “especially given the devastating effect it is having on renewable energy”.

“Possibly, the scale of this is not as huge as other things. Perhaps the market does not have the time and resources to escalate this to the appropriate level. Or, perhaps they are too hung up on Consumer Duty. But I otherwise do not know why the FCA has buried its head in the sand.

“But it affects lots of smaller businesses. This does not take away from its importance, especially given this affects parts of the market with no alternative means of fundraising.

“It’s pretty dire and the entire investment trust sector could end up getting killed off.”

Solutions

A number of solutions have been offered by investment professionals. The AIC has been calling for a layered approach to cost disclosure for a while. However, not everybody believes this is the best solution.

MacLeod argued this “would be technically impossible to do”, given the way in which charges data is disseminated to fund-of-fund and wealth managers.

“Currently, a single line of data is inconsistently calculated, using a variety of sources, and distributed by ACD’s for every fund in the UK,” he said. “It is sent to primary and secondary information providers who publish the figure with varying degrees of accuracy. From there it is sent straight into clients’ investment reports. Can you imagine the confusion if one line of synthetic costs became many?”

Instead, he believes the information published in a KID – which he understands “are rarely downloaded” – should be absorbed into a fund’s factsheet, which is currently a marketing document and “widely read”.

“You would have a standard box of information made available to all investors – be they retail or professional – and all contained in one place,” MacLeod explained.

“By amalgamating the two documents and regulating elements of the content the investor would be presented with standardised and clearly presented information; the value of the factsheet should not be underestimated. They are used by investors of all levels of sophistication and downloaded and read in vast numbers every day.

“Investors would benefit from enhanced and regulated content as well as important information, such as market commentary (often the only direct communication between fund manager and investors), performance data, costs, share classes and accessibility. Adopting the factsheet in this way would be helpful to all investors. We know they are consulted and read as the principal source of information, so why not make them work harder for everyone’s benefit?”

Will trusts survive?

Brodie-Smith is optimistic that investment trusts will come through the other side of the crisis.

“Investment trusts have been in existence since 1868 and are the oldest form of collective investment,” she said. “Investment trusts have weathered the World Wars, the Great Depression, the recessions of the mid-1970s, the financial crisis and the pandemic. They continue to deliver strong total returns for investors and continue to adapt to meet investors’ needs.”

Others are less sure. MacLeod said this is different from a market shock in that the headwind “has been foisted upon us”.

“Like a balloon with a pin prick, we’re watching as things slowly deflate,” he warned. “The irony is that the pin and the sticking plaster are in the same hands.”

Parfect said the guidelines are akin to “throwing sand into an otherwise well-oiled machine”.

“Normally the machine will cope with the added strains of going uphill (such as when bond yields are rising), however these guidelines are at best friction against the wheels and cogs, and at worst cause lasting damage and for the machine to suffer a complete breakdown.”

Baroness Bowles said the FCA “should respond quickly to an emergency like this”.

“It should do something,” she urged. “Even if it decides it doesn’t want investment companies anymore, the FCA should be prepared to say that and let markets invent their alternative.

“Does it want investment companies or doesn’t it? Is it going to call time on them? Because that’s what the FCA is facing.”

In response, a spokesperson for the FCA said: “Transparency about both costs and charges and risk form an important part of the regulatory framework, so consumers and those acting for them know what they are paying for.

“We do know that some disclosure requirements can be improved. We have already taken action and have committed to designing a new disclosure regime which will consider what the right way to disclose costs and risks should be. We have previously intervened to ensure PRIIP manufacturers can provide appropriate risk disclosures.

“Many of the detailed requirements about disclosure are legislative and will require the Government to make changes.”