Negative US bond yields may be a more likely prospect than you think. Although negative rates have been used in Europe and Japan, it had been widely assumed the US would not follow a similar path. Indeed, as recently as 15 March this year, Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell dismissed the likelihood of using negative interest rates to stimulate the US economy saying: “We do not see negative policy rates as likely to be an appropriate policy response here in the United States.”

Our own base case is that a combination of close to zero policy rates and QE will be the route of choice for the Federal Reserve – indeed, that has been our view for some time. These are not normal economic circumstances, however, and negative interest rates may become the key tool used by the US and other global central banks as they try to prevent a global recession becoming a global depression.

Before expanding on the rationale for negative rates, we need to put the current economic conditions into context. On 26 March, the latest US initial jobless claims figures were announced.

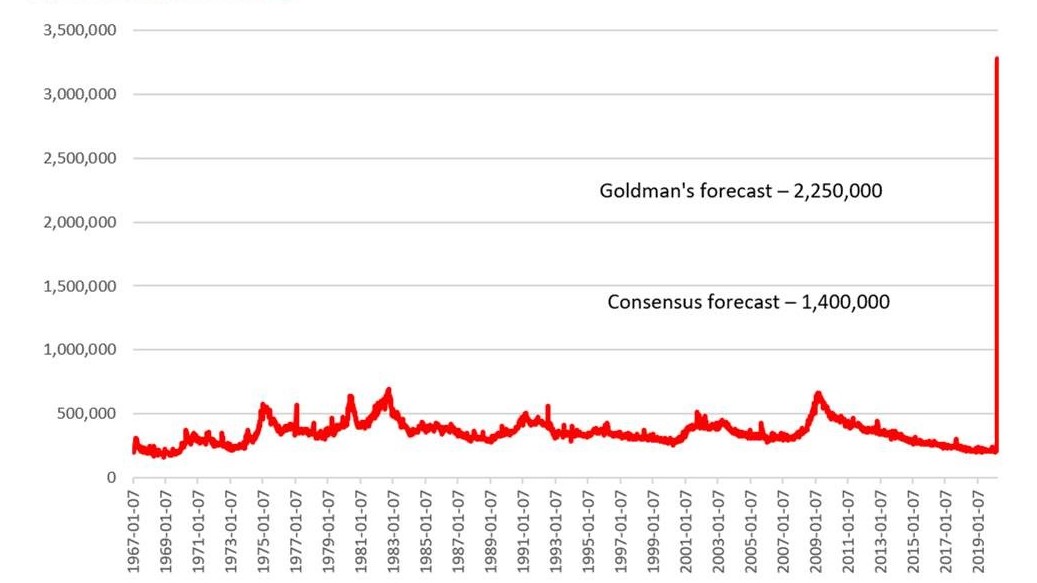

Chart 1: Initial jobless claims

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

Before the release, consensus was for a figure of 1.4m initial jobless claims, with Goldman Sachs forecasting 2.25 million. The true number announced was more than double the consensus, however, as the US Labor Department announced jobless claims filed rose by more than 3 million to 3.28 million from 281,000 the previous week. To say these figures dwarf those seen in all previous recessions is an understatement.

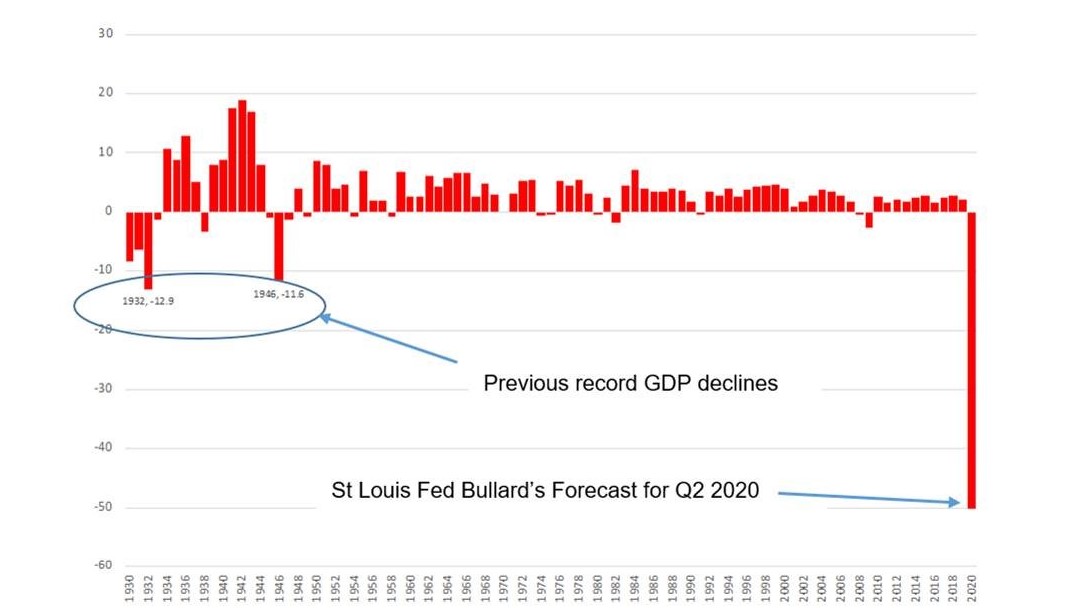

These are unprecedently large numbers and translate into GDP and unemployment forecasts not seen since the Great Depression of 1929/33. Forecasts vary, but St Louis Fed president James Bullard recently predicted the US unemployment rate may hit 30% in the second quarter with a jaw-droppingly large 50% decline in GDP owing to outbreak-induced shutdowns.

To put this into perspective, the previous record lows were in 1932 when US GDP contracted by 12.9% in real terms and in 1946 when the economy contracted by 11.6%. To be clear, Bullard’s 50% contraction figure is only for the second quarter but, without knowing when the virus will allow any semblance of a return to normality, it is hard to know whether the economic contraction will be short-lived or continue for a sustained period. Whatever the economic damage, it is likely to be on a gigantic scale.

Chart 2: US GDP 1932 – 2020

Source: BEA

Credit where it’s due

Negative rates will be a last resort but policymakers are trying to find ways to provide credit where it is needed. In a recent interview, European Investment Bank head Werner Hoyer neatly summed up the European problem, which equally applies to the rest of the world. He observed that Europe urgently needed a massive lending programme to help small and medium-sized companies across the region weather the coronavirus crisis, which should be obvious to most people.

Less immediately obvious, but undoubtedly true, Hoyer also observed: “Either we decisively save European companies now, or we will soon have to save European states from financial collapse.” He went on to add, however: “It doesn’t seem to me that everyone in European politics sufficiently understands this.”

While Hoyer was referring to Europe, it is not clear that US politicians have yet grasped the enormity of the problems faced. Partly as a consequence, credit spreads are at levels that suggest a lack of willingness by market participants to lend to even strong investment grade credits. Consequently, the Fed may be forced to do more of the heavy lifting.

First up seems to be a new initiative by the Fed – the establishment of a Main Street Business Lending Program to support lending to eligible small-and-medium sized businesses. While we have little in the way of detail at present, it is likely the Fed will guarantee all or a high proportion of loans extended by banks. That will clearly be helpful.

Negative yields

Another route that achieves a similar outcome – albeit in a way that appears less interventionist – would be to set five or 10-year yields at a negative yield and purchase unlimited amounts of Treasuries at the new negative rate.

This would achieve several things at once. First, it would boost the price of Treasury bonds, improving the balance sheets of those with risk-free assets on their books. Second, it would allow holders of Treasuries (and mortgage bonds) an easy exit in order to obtain much needed liquidity.

More importantly though, the displacement of market participants would force them into corporate credits, causing spreads to tighten. Provided spreads narrow sufficiently, those firms that need longer-term funding will be able to do so using traditional market mechanisms.

The major beneficiaries of such a policy would be the highest-rated investment grade credits – particularly quasi-sovereigns. Some high yield credit may also benefit from this. Until confidence is fully restored, however, highly leveraged companies faced with a collapse in demand may not be able to fund themselves at any price, regardless of the policies implemented by governments and central banks.

Andrew Seaman is chief investment officer at Stratton Street Capital