The growth of investment companies targeting alternative assets is one of the biggest trends the industry has experienced for almost two decades. As the following table shows, at 31 August 2021, some two-fifths (39%) of investment trusts – excluding VCTs – had alternative mandates. That represented £98bn worth of assets – up from £30bn in August 2010.

How alternative investment has grown within investment companies since 2010

| Date | Total no. of ICs (ex VCTs) | Total no. of alternative ICs | Total assets within ICs (ex VCTs) | Total assets within alternative ICs |

| 31/08/2010 | 345 | 116 | £88bn | £30bn |

| 31/08/2021 | 333 | 129 | £259bn | £98bn |

Notes: Number of alternative mandates has grown from 33% of total investment companies (ex VCTs) to 39%. Total assets within alternative mandates has grown from 34% to 38%. Source: QuotedData, AIC

In the past five years alone, as our next table shows, 37 alternative investment companies have launched out of a total of 60 IPOs across the sector – and even year-to-date there have been nine new issues, six of which offer alternative mandates from infrastructure to leasing. There are also a further three currently at the pre-IPO stage: Foresight Sustainable Forestry, Harmony Energy Income and Pantheon Infrastructure.

Breakdown of investment company IPOs over the past five years

| Year | Total no. of IC IPOs | No. of ‘alternative’ IPOs |

| 2021 pre-IPO | 3 | 3 |

| 2021 YTD | 9 | 6 |

| 2020 | 8 | 5 |

| 2019 | 8 | 5 |

| 2018 | 20 | 10 |

| 2017 | 15 | 11 |

Source: QuotedData, as at 31/08/21

The popularity of such products is the result of a combination of factors, including the hunt for income, the need for diversification and, more recently, a stronger focus on ESG – as seen, for example, in the renewable energy infrastructure sector.

Arguably the biggest reason, though, for the increase in these mandates in the investment trust world in particular is because the closed-ended structure is seen as a more suitable vehicle for alternative asset classes. This is because illiquid investments, such as property and private equity, cannot be sold at short notice. If held in an open-ended fund, therefore, there is greater risk for shareholders if a sell-off is triggered as there is a liquidity mismatch.

In 2016, for example, after the UK voted to leave the European Union, almost every open-ended property fund was forced to suspend trading. Panic about the viability of UK commercial property shot through the market, leading anxious investors to rush to withdraw their money.

Just like a homeowner trying to sell their house, property fund managers could not sell their holdings at a moment’s notice and so they could not pull together the cash quickly enough to pay investors back. The only way to stop the funds collapsing was to gate them. A similar scenario played out – albeit not as extremely – in 2020 as the coronavirus pandemic rocked markets.

Closed-ended funds on the other hand do not have to worry about daily inflows and outflows, and their stock exchange listing means investors can buy and sell shares whenever the market is open, without the risk of suspensions. This means investors can sell shares without the trust literally having to sell a building to meet the liquidity, as is the case in open-ended funds.

Stuck in limbo

Another high-profile instance can be seen in the widely reported Woodford saga, which saw investors scrambling to pull their money out of the fallen-from-grace Woodford LF Equity Income fund before they were locked out in the summer of 2019.

Two years on, more than £120m of investors’ money is still stuck in the fund, with an update in August 2021 saying it “continues to make progress regarding the sale of the remaining assets” and that “it is hoped that the sale of the remaining assets will be concluded in 2022 [though] it is not possible to provide a definitive end date”. By comparison, while investors in Woodford’s closed-ended Patient Capital trust – now Schroder UK Public Private trust – did see performance plummet and its discount widen, they had the choice to stay or go.

Open-ended fund managers may try to mitigate the risk that comes with mass redemptions by holding a proportion of the fund – often around 20% – in cash or very liquid investments. While this cash is still at risk of running out if everyone tries to withdraw their money at the same time, it also means the fund is not putting all its investors’ money to work, thereby creating ‘cash drag’.

Investment trust managers are not only able to use all their balance to find the best investments, they also have the option to gear – that is to say, to borrow more money so they can invest in further opportunities. As an example, Civitas Social Housing – a member of the Property – UK Residential sector, which has benefited from the increasing importance of age care and build-to-rent living – currently has 30% net gearing, likely due to the abundance of opportunities available. As reported in its latest annual results, the company acquired 25 supported living properties in the 12 months to 30 June 2021 while also identifying a pipeline of more than £200m.

The ability to gear also means the potential to amplify returns, including income. Yields for leasing, infrastructure and other alternative asset classes are similar for both open-ended and closed-ended funds but returns can be diluted in the former due to the need to hold a higher cash balance. That said, investors do need to be aware that, while gearing means access to further opportunity and potentially higher returns, on the downside, any losses will also be amplified.

Discount risk

Investors should also be conscious of discount risk. A discount is where the value of a trust’s shares sits below the value of its net assets – that is, the value of its assets, less any liabilities, for example borrowings it might have. Similarly, a premium is where a trust’s shares are trading at a price greater than its net assets.

When there is stress in a particular industry or the market more generally, prices can be especially volatile. For illiquid assets, valuations tend to be more stable, meaning the net assets of a fund invested in these are also more stable – although there can be a knock-on effect whereby discounts, and sometimes premiums, can quickly emerge.

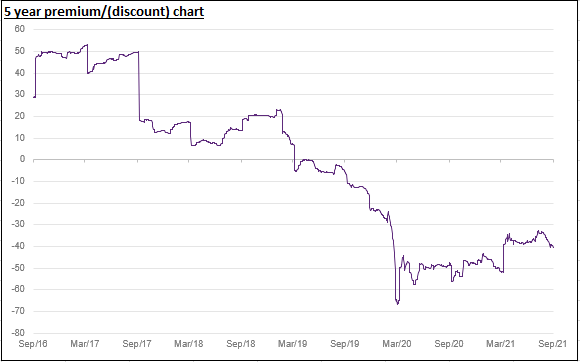

As global lockdowns were enforced at the height of the pandemic in March 2020, for instance, the almost entire suspension of the aviation industry around the world hit the premiums of a number of leasing trusts hard, as the following chart illustrates. DP Aircraft, for example, saw its discount slump from 20% at the start of 2020 to 73% by 23 March 2020 – the day the UK went into a national lockdown – while Doric Nimrod Air Three started the year on a 2% premium before swinging to a 53% discount less than three months later.

Average of premium/discount of aviation-focused trusts in the leasing sector

Note: Trusts included are Amedeo Air Four Plus, Doric Nimrod Air One, Doric Nimrod Air Two, Doric Nimrod Air Three, DP Aircraft. Source: QuotedData, Morningstar

Similarly, a number of infrastructure funds including HICL Infrastructure, which usually trade on comfortable premiums, swung to discounts in 2017 after the shadow chancellor at the time, John McDonnell, scared investors with a speech in which he claimed private finance initiatives were draining resources from the NHS and vowed to bring these contracts back ‘in-house’. Since then, nationalisation concerns have eased and nine out of the 10 members of the infrastructure sector are back to trading on premiums, half of which are in the double digits.

Investors could well have sold their holdings but, unlike those at the mercy of a gated open-ended fund, if they had chosen to do so, most would have been set to make losses, the severity of which would be determined by where the discount/premium was when they made their initial investment.

The key benefit here is that investors have the free will to do what they want and are – usually – well-informed enough to know the consequences. Should they leave, they may face losses that can be calculated relatively straightforwardly. Should they stay, discounts may widen further, but they may also narrow and move to a premium over time – as eventually happened with the infrastructure sector.

To that effect, most investors would argue avoiding knee-jerk reactions and staying put would be the best way to go. After all, investment trusts are all about the longer term.

Jayna Rana is an investment companies analyst at QuotedData