In the early months of the global pandemic, we questioned whether more British companies would get the ‘buyback bug’ in an article for the Portfolio Adviser website, after high-flying dividend payers were forced to halt or scrap shareholder payouts.

Flash forward two years and UK plcs, flush with extra cash after recovering from their Covid lows, are taking advantage of recent volatility to snap up their own shares on the cheap.

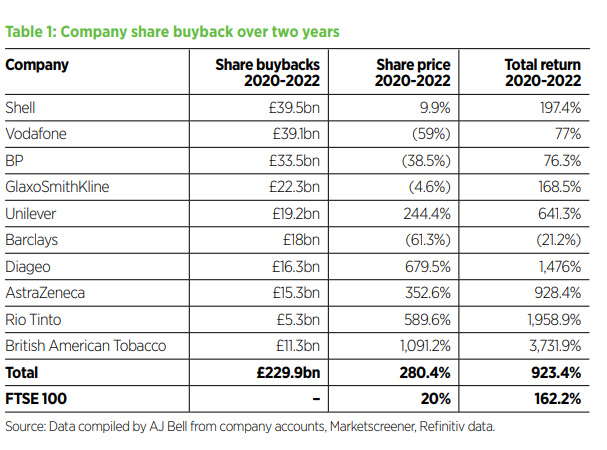

Just three months into 2022, FTSE 100 constituents have already announced £33bn worth of share buybacks, according to data from AJ Bell. This is higher than the £25.3bn that Britain’s biggest businesses returned to shareholders for the entirety of 2021 and within touching distance of a record £34.9bn in 2018.

Cyclical stocks, which have been out of favour until very recently, have been driving the UK’s buyback bonanza this year. Financials have unveiled £10.5bn in buyback schemes so far, the highest of any sector, with battered banks Lloyds and Natwest each launching £2bn programmes.

Oil and gas giants are next up, having committed up to £7.4bn in share repurchases off the back of surging commodity prices.

But in the UK, dividend culture is still deeply rooted. The £25.3bn of FTSE 100 share buybacks confirmed in 2021 was a third of the £74.1bn paid out in ordinary dividends, not including £5.8bn of special dividends, according to AJ Bell.

Still shrouded in controversy

Still, UK investors seem to be warming to the idea of share buybacks. Even staunch quality growth manager Nick Train, who prefers companies that “scrimp on dividends” and reinvest their earnings, spent his last communication to Finsbury Growth & Income shareholders highlighting the raft of buybacks in the portfolio.

“We are encouraged how many of our companies are buying back shares currently, because we agree with their boards. These shares being retired could well be undervalued,” he said.

In theory, share buybacks should be an easy win for businesses and their shareholders. A company decides it is being undervalued by the market and offers to buy back its stock directly from the market or from existing shareholders, typically at a fixed price. This restricts overall supply, driving up the value for loyal shareholders.

However, these multibillion-pound schemes are still shrouded in controversy. Critics claim they are merely a tool for top executives to line their pockets by massaging earnings per share (EPS) figures to trigger bonuses or stock options.

In the US, home of the share buyback, Joe Biden is pushing for new rules that would bar C-suite members from selling stock for years after a buyback, following research from the Securities and Exchange Commission of managers using schemes as an opportunity to cash out.

There is little evidence to show buybacks increase value or boost share prices over the longer term, says Richard Hunter, head of markets at Interactive Investor.

This is “partly because the percentage of shares being repurchased compared with those remaining in issue is usually minimal”, he explains.

More buybacks happen around market tops

Gresham House UK Multi Cap Income manager Ken Wotton finds companies’ objective for launching share buybacks is “quite woolly”, meaning “measuring the effectiveness is also not usually very clear”.

This is in sharp contrast to investment trusts, he notes, which can use buybacks “effectively” to defend a discount to NAV.

Another point of contention is how companies determine their shares are cheap. AJ Bell investment director Russ Mould points out that, historically, share buyback activity tends to peak near market tops and wane when they bottom out. From 2006 – 2007 there were over £60bn worth of FTSE 100 buybacks but this slowed to just £3bn in 2009, a year after the global financial crisis hit and stock prices remained collapsed.

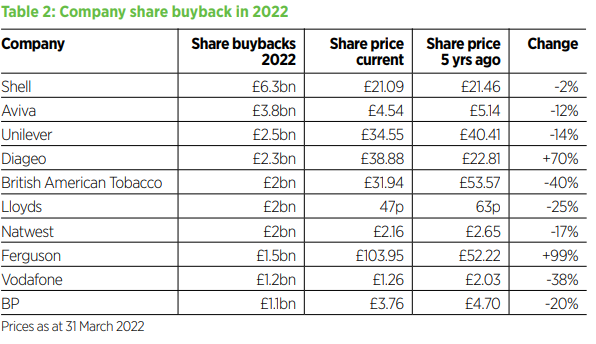

Some of the FTSE 100 companies that have announced the biggest buyback schemes in 2022 are trading on large discounts. Lloyds and Natwest have seen their shares in the doldrums amid the ultra-low interest rate environment. They are down 25% and 17%, respectively, compared with five years ago. British American Tobacco and Vodafone have slumped even further.

But spirits maker Diageo has launched a buyback programme despite its shares being worth considerably more now than five years ago and falling just 5% in 2022. Heating and plumbing distributor Ferguson’s shares doubled over that same period, although they are down 22% year to date.

Buybacks destined to take off in the UK

While Gam UK Equity Income manager Adrian Gosden (pictured) admits “share buybacks aren’t for everyone”, ultimately, he is a proponent of them.

“Share buybacks are very positive as they decrease the denominator in the EPS and dividends per share. And if you can buy your own shares on a discount to NAV then it is very much better than investing in the business which is equivalent to NAV,” he says.

They are also good news for income investors. “You do not cut a dividend if you are doing a share buyback.”

Like the recent surge in M&A deals and private equity buyouts in the UK, Gosden says the trend for share buybacks will “percolate” across all sectors and market caps.

“It will become a standard question to management from investors: Are you going to do a share buyback?”

A legitimate option

Evenlode Global Income manager Ben Peters is agnostic when it comes to companies using buybacks versus dividends to return cash to shareholders.

He points out that buybacks are more flexible than dividends. “You can turn your buyback off because you don’t want to spend so much capital but if you cut your dividend, everyone knows about it.”

On the flip side, with dividends investors know the price upfront.

Jordan Sriharan, multi-asset fund manager at Canada Life Asset Management, points out that for the oil and gas giants, share buybacks may seem like one of the only sensible ways, alongside dividends, to make use of excess cash.

Since the oil price tanked in 2014, energy firms have been more disciplined about their capex spending, which reached dizzying heights in the years after the financial crisis. The rise of ESG and global climate change initiatives has also constrained the types of activities they can invest in.

“Oil companies are not spending as much cash because they’re acutely aware that their future is diminished somewhat,” Sriharan says.

“It’s not in their interest to start spending on more drilling sites because it’s quite clearly in everyone’s interests for that to stop.”

No ban necessary

Despite the shaky track record of buybacks in the UK, Hunter does not think they should be banned.

“Buybacks remain part of a company’s armoury in distributing surplus cash,” he says. “If they were outlawed or excessively taxed, it is difficult to argue the cash which would simply now be sitting on the balance sheet would be adding any more value.”

Mould says buybacks that are run in a “disciplined manner”, where a company has clearly set a maximum price they are prepared to pay and explained why, could help create shareholder value.

“But if a company buys shares at any price, something that could get a professional fund manager the sack for poor performance […] its buyback programme should be treated with scepticism.”

Next is a “rare and shining example” of a company that has gotten buybacks right, Mould argues. Unlike so many of its FTSE 100 peers, the fast-fashion retailer “does not buy back stock willy-nilly at any price” but when the purchase brings it an equivalent rate of return of 8%, which is calculated by dividing pre-tax profit by market cap.

“Next paid out £2.3bn in dividends and £1.9bn in buybacks over the past decade. Those buybacks have taken the share count down from 181m to around 127m, increasing the stake of anyone who chose not to sell by almost a third.”

Wotton would prefer management teams launch a tender offer with a clear message about why their shares are undervalued. “If this is compelling, the shares should re-rate and there will be limited take-up of the tender. If the tender is subscribed and management are correct, then it should create value for remaining shareholders.”

‘There are egos involved’

The buyback trend has been slower to take off in asset management. With a few exceptions like Man Group and M&G, fund group chief executives have mostly preferred going down the M&A route to grow their businesses at a time when passive managers are eating active managers’ lunch.

But, historically, not many active managers have made a great success of growing through acquisition. Outflows have persisted at Abrdn and Jupiter despite their respective tie-ups, and the former’s market value has halved since the merger of Standard Life Investments and Aberdeen AM.

See also: Man Group’s £190m share buyback thrusts spate of M&A deals in the spotlight

Gosden believes more fund management groups should buy back shares. “Those companies that do not grow are valued on PE 8x and yield an 8% dividend, for example Premier Miton or Jupiter. They have cash balances.

“But there are egos involved. CEOs want to grow their companies organically or by acquisition. At those valuations, the best thing they can buy is themselves.”

This article first appeared in the April edition of Portfolio Adviser Magazine