The UK consumer price index (CPI) stands at its highest point since July 2019 – 2.1% for May – and trending steeply upwards, bouncing sharply from February’s level of 0.4%. That it has gone up like a rocket (whether that is one of Bezos or Musk provenance) does not mean it will continue to, of course.

As inflation peaked above 3% in November 2017, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) reported it stood “ready to respond to changes in the economic outlook as they unfold to ensure a sustainable return of inflation to the 2% target”.

Despite claims of limited slack in the economy and reviving growth, however, CPI continued to trend down to 1.3% in December 2019 – followed, as Chart 1 shows, by the pandemic-induced nosedive. Although, to be fair, one can hardly criticise the MPC for not seeing that coming.

Chart 1: UK CPI, 2016 to 2021

We will take a look at the how UK investors are reacting to this further down, but first let’s cast an eye over how those Delphic Oracles of modern times – otherwise known as economists – are interpreting the return of inflation.

Boffins say …

There are, broadly, two linked drivers for inflation: the post-pandemic recovery; and the stimulus packages intended to embed and accelerate it – not least president Joe Biden’s $1.9trn (£1.37trn) relief package in the US. One resultant inflationary pressure is the tightening US job market, as indicated by the June spike in vacancies. Employing some fairly fruity language, the senior economist of employment service Glassdoor, Daniel Zhao, exclaimed “holy moly!” to the 100% year-on-year rise in US job openings.

There are, broadly, two linked drivers for inflation: the post-pandemic recovery; and the stimulus packages intended to embed and accelerate it – not least president Joe Biden’s $1.9trn (£1.37trn) relief package in the US. One resultant inflationary pressure is the tightening US job market, as indicated by the June spike in vacancies. Employing some fairly fruity language, the senior economist of employment service Glassdoor, Daniel Zhao, exclaimed “holy moly!” to the 100% year-on-year rise in US job openings.

For its part, investment research provider TS Lombard tweeted that “the price increases of today will pass, the Fed’s inflation problem begins sometime next year,” and reckoned “for now markets are overreacting.”

Fathom Consulting meanwhile observes: “While some of the key drivers of the rising inflation rate are transitory, it remains to be seen how supply shortages and potential rising demand could affect prices in the medium term.” As such, it holds has a relatively sanguine view of the return of inflation over the longer term.

“Absurd” is the word Oxford University professor of economics Simon Wren Lewis uses to describe fears of an inflationary spiral at this time, arguing: “The end of pandemic will see an increase in pent-up consumption, but that is a very temporary affair.”

Lastly, Gertjan Vlieghe, external member of the MPC, in a speech in May, delved deeply into the inflation question. In an analysis based on US and UK bond yields, he expects US inflation temporarily to overshoot – not least because the country “has added a larger fiscal stimulus than the UK into an economy that suffered a smaller Covid set-back than the UK,” but that “survey evidence in the UK remains consistent with the MPC’s target. And there is no sign so far of emerging risk to the credibility of our target, either from surveys of inflation distributions or inflation options”.

Consensus, then, is that we are experiencing a post-pandemic reversion to the mean and that the economy is unlikely to see entrenched price rises significantly above the Bank of England target rate of 2%. The inference is that both inflation rates and base rates will rise, but modestly.

Place your bets

Does this align with investor expectations, then? As markets rebounded in last autumn’s Covid rally, some picked up on the issue of inflation, and began to allocate accordingly – albeit skewed towards US assets than UK (as outlined in Refinitiv Lipper’s 2020 UK fund flows analysis, p12).

Flows to Bond GBP Inflation Linked Lipper Global Classification funds, although negative £503m over 2020, saw a steady increase in flows from -£828m in Q1 to £310m by Q4. What is more, Bond USD Inflation Linked funds took in considerable assets over the year – especially in Q2 and Q4, when markets rallied significantly.

Over three-monthly periods, UK inflation-linked bond flows were uninterruptedly negative between February 2018 and May 2020. Flows for this fund classification have ticked up since then, however, and are at their highest volumes since May 2017. To gauge how significant this is, we looked at the ratio of Bond GBP Inflation Linked to Bond GBP Government flows and found the 10-year average to May 2021 is 0.13. In the three months to that date it was 0.37, and the three months before that 0.43, so linkers are building up steam relative to conventional gilts.

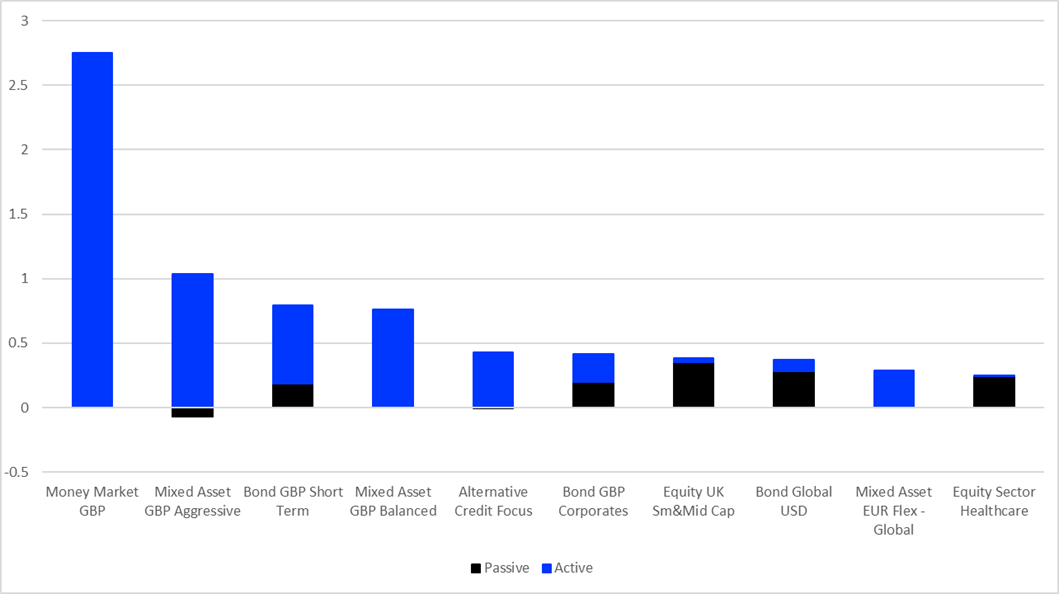

Chart 2: Largest positive flows by Refinitiv Lipper Global Classification, May 2021 (£bn)

Source: Refinitiv Lipper

Despite this, during 2020, £3bn exited Bond GBP Short Term, a fund classification where flows run in the same direction as inflation expectations. In May 2021, however, these funds saw net inflows of £792m – the third largest for the month, as Chart 2 shows – combined with -£369m outflows from Bond GBP, signalling a significant rise in UK inflation expectations.

A single swallow does not a summer make, of course, and flows for the three months to the end of May are still negative – as they have been since last August. Again, one should not read too much into one month’s data, so it will be interesting to see if this is a blip or becomes a trend.

Taken in the round, however, UK investors are becoming more alert to the potential dangers of inflation – whether that is by selling out of longer-dated bond funds and putting money into shorter-duration ones, or through buying inflation-linked bond vehicles. Whether this is prudent hedging against a temporary uptick or bulwarking against the awakening inflationary beast is – as Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai is supposed to have said in 1972 of the impact of the French revolution – too early to tell.

Dewi John is head of research UK & Ireland at Refinitiv Lipper