The framing of our view on the UK equity market is premised on four points: a three to five-year time horizon; its relative valuation to the developed world peer group; the fact that right now virtually nobody wants to invest in the UK; and that this is regardless of any Brexit outcome.

A three to five-year time horizon

This is broadly speaking the minimum investing period we would have for any asset class. It’s important to understand this because there will continue to be a plethora of mostly negative headlines in the coming months.

Somewhat ironically, with each new blow further depressing sentiment, the investment case becomes stronger. In particular, it gives the best active managers the chance to buy UK companies at a discount to similar assets in other countries simply because they are UK assets.

If you can accept the heightened level of volatility over issues such as Brexit and Covid-19, which will undoubtedly be here for the coming months, then you can see the investment opportunities in a very different light.

We are witnessing some very successful longer-term managers, such as Polar Capital’s George Godber, Man GLG’s Henry Dixon and JOHCM’s Alex Savvides, experience some of their poorest performance of their careers. It is our assertion that this will not continue for too much longer and that we will look back at the UK’s investing nadir as one of the best opportunities in a career to own their funds.

Another quarter or two of relative underperformance does not change the long-term investment case.

That said, we feel as ever that it’s vital to hold multiple funds in a sector as no manager comes with a guarantee of returns. We also limit ourselves to a maximum holding of 4% in any one fund as an additional safeguard for our clients. The standout manager for us has been SVM’s Margaret Lawson, who has done an incredible job of working out the winners in what is still a very new world for all of us.

Relative valuation

The relative valuation to the developed world peer group of the UK has seldom, if ever, been this attractive. Not only do we have the idiosyncratic and unquantifiable headwinds of any Brexit outcome but we have our main equity index, the FTSE 100, stuffed full of big oil, banks and insurers.

In other words, a collection of stocks that are the last things most people want to own right now, and then of course we have a dearth of large tech firms, though this last point is also a wider European issue, not just a UK one. So, the UK finds itself also on the wrong side of the value versus growth debate.

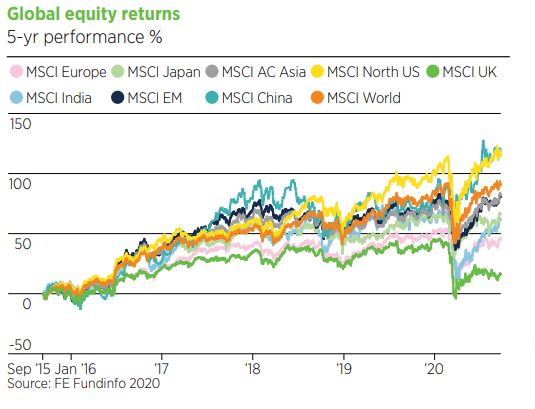

Tom Dobell, the veteran M&G Recovery manager, recently announced he is stepping down and he becomes the latest value manager to part ways with their employer. As the chart illustrates, any asset allocator who has avoided the UK over the past five years has done well. In fact, to be a UK value manager and have kept your job during the past few years has been an achievement in itself.

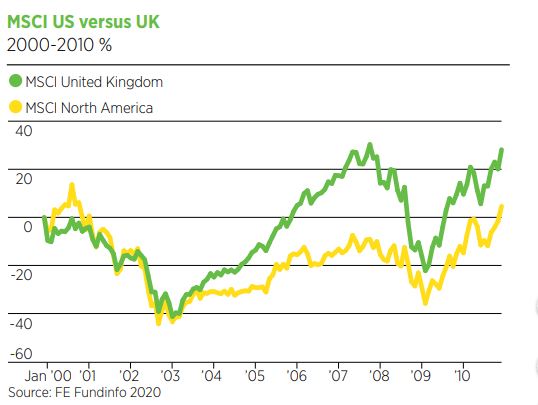

On top of the genuine issues facing the UK and value stocks in particular, we believe there is also a degree of recency bias at play here. Right now, it’s all about the US and nobody even talks about how the 2000s were a lost decade for US stocks. It’s tech all the way and even though the fully paid-up members of the cult of tech are now struggling to justify some of the mind-boggling valuations, it doesn’t really seem to matter. One day it will, however.

On top of the genuine issues facing the UK and value stocks in particular, we believe there is also a degree of recency bias at play here. Right now, it’s all about the US and nobody even talks about how the 2000s were a lost decade for US stocks. It’s tech all the way and even though the fully paid-up members of the cult of tech are now struggling to justify some of the mind-boggling valuations, it doesn’t really seem to matter. One day it will, however.

The salient point is obviously these statistics are all backward-looking, and we don’t expect the next five years to look like the last five; in fact, if we are certain about anything it’s this.

The ‘new world’ for us started in Q4 2018 with the infamous Powell pivot. This was when the chairman of the US central bank went from talking about interest rate rises, balance sheet roll-off and using terms like ‘normalisation’ to a complete capitulation to the US equity markets.

By the end of the last quarter of 2018, the concept of normalisation had been consigned to the flames of hell and never spoken of since.

Unlike the UK, which couldn’t see past any Brexit fallout, the US realised for the first time in history that if markets fell, the central banks would effectively push them back up again. In the past two years there has been rational exuberance in many risk assets in different parts of the world, but not so the UK equity market, and this gives us potentially less downside risk in certain circumstances.

Unloved UK

Nobody wants to invest in the UK and if we were looking at a three- to six-month time horizon we would agree there are just too many risks; but that just increases the opportunity. The UK has companies with excellent corporate governance, some world-beating products and a long history of entrepreneurship.

We also have the advantage of our own currency, which can and has done some of the heavy lifting in the post-vote era. We have the further theoretical advantage of our own central bank, which sets rates for the UK and the UK alone. In theory, this should be much simpler than, say, trying to set a rate that works for both Germany and Greece.

We say ‘in theory’ because as all developed countries have pushed their rates to zero, and often beyond, the reality seems to matter less and less. It’s certainly not a disadvantage and at some point in the future it may matter more again. No circumstances prevail indefinitely.

While it is true we have a reliance on banks, oil and mining as well as our service sector, we see these areas that will need to adapt; and the quicker the better. Whether it’s the green agenda or low interest rates for longer, each sector has its issues, but there will also be new winners.

Brexit outcomes

The UK voting to leave the EU in 2016, and then effectively doing so again by voting for Boris Johnson in 2019, has caused considerable debate about the UK turning inward amid a new wave of nationalism.

We think this is partly correct, but we are by no means alone. While some countries such as the US under Trump make a big show of attempting to onshore jobs and put their own country first, many others are doing it without the fanfare. With a backdrop of Covid, which has merely brought forward much of the ‘put your own country first’ mentality, this is the new direction of travel.

This in turn will bring new winners and losers. One of the things the economists find difficult to model is entrepreneurship, and this is an area where the UK excels. Where it has often failed is in retaining the companies and products long enough to realise their value, which ends up going abroad. This is hopefully something that will now change, but in any event the UK remains a good place to do business and a place where many people want to live.

Covid also gave us a good example of a doomsday scenario, which has so far turned out to be incorrect. The headlines at the beginning of the breakout were full of stories of collapsing house prices. Governments have been keeping house prices elevated for years, and this one was not about to stand idly by and watch the market fall.

We cannot predict what plans the government will have following any of the myriad possible Brexit outcomes, but doing nothing is unlikely to be one of them.

Markets don’t like uncertainty, we all know that, but for the first time in more than four years, we might be about to get less of it.